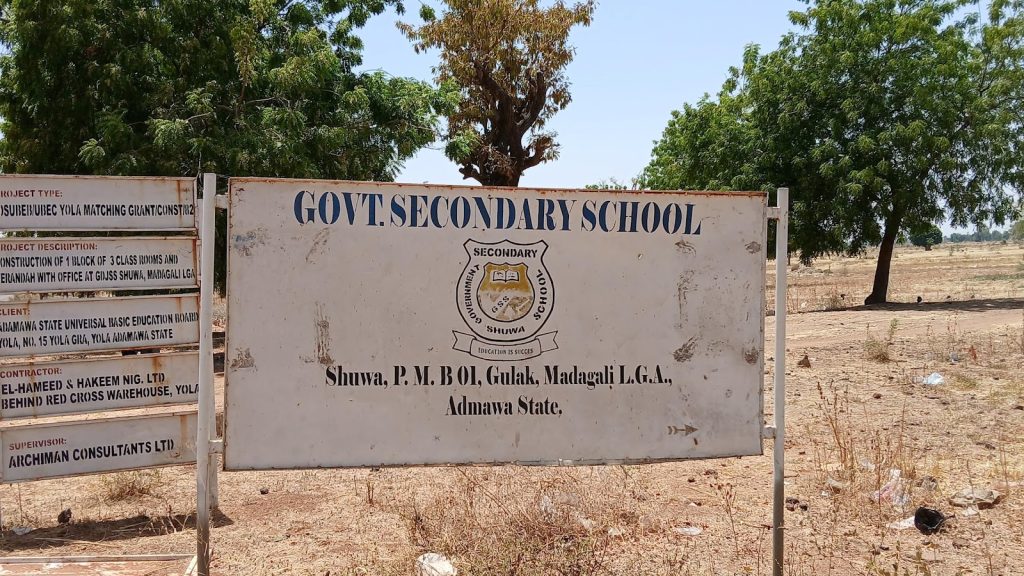

“They Tried to Burn It All”: Adamawa School Struggles to Rise From Boko Haram’s Ashes

Over ten years after Boko Haram's brutal attack, Government Secondary School Shuwa, still stands in the shadow of its trauma—its buildings broken, classrooms nearly empty, and scars still fresh. Yet in the face of fear and neglect, a determined community clings to hope, fighting to reclaim education as a path to healing and survival.

One afternoon in March 2014, Paul Daji, newly appointed principal of Government Secondary School (GSS) Shuwa located in the Madagali area of Adamawa, northeastern Nigeria, was in his office when he heard the loud sounds of gunfire. As he rushed outside to find out what was happening, he saw armed men in military uniforms approaching on motorcycles and trucks.

He initially assumed they were Nigerian soldiers. They weren’t.

They were fighters from Boko Haram.

“It was chaos,” Daji recalls. “Students were screaming, teachers were running in every direction. It was like the world was ending.”

That evening, as bullets rained down and panic seized the school compound, the insurgents spread into Shuwa village, looting food stores and ransacking shops before vanishing into the forest.

Days later, they returned, this time attacking a faith-based school in the community. The life of its principal, who was Paul’s colleague and acquaintance, was cut short.

The message was clear: education was a target. The trauma, immediate and far-reaching, forced families to flee in droves. Schools emptied. Homes were abandoned. A quiet town became a shadow of itself.

The Long Road Back

Today, more than a decade later, the scars of those attacks remain etched in the crumbling infrastructure of GSS Shuwa. Walls bear bullet marks. Roofs leak when it rains. Classrooms, where learning once bloomed, are hollowed shells of what they used to be.

After the Nigerian military reclaimed the area in early 2015, hope flickered. But GSS Shuwa didn’t reopen until 2016—and even then, the return was painfully slow. Most of the teaching staff had sought safer employment elsewhere. Many children never came back. Entire families resettled in other towns, unwilling to risk another tragedy.

Paul Daji, however, stayed.

“The school was a ghost town when I came back,” he says. “But I knew we had to start somewhere.”

That “somewhere” meant holding classes under trees or in half-collapsed buildings, sharing textbooks among groups of five, and going without running water or electricity. To this day, essential infrastructure is missing. There’s no fence, leaving the school exposed. Laboratory equipment and computers are a luxury the students can only imagine.

Aside from Shuwa, the broader Boko Haram conflict, which has for years been ravaging communities across northeastern Nigeria, has directly targeted students, teachers, and educational infrastructure, resulting in widespread school closures and severely disrupting learning across the region.

By the time GSS Shuwa fully resumed operations, Paul, in his role as the coordinating principal for schools in Madagali, teamed up with his colleagues from other affected areas to collectively request immediate intervention from the Adamawa State Ministry for Education and Human Capital Development.

Despite these efforts, schools in Madagali, including GSS Shuwa, struggled to provide a safe learning environment for students until 2022, when the Adamawa government’s approval of renovation funds brought a much-needed glimmer of hope.

What Lies Ahead

For GSS Shuwa to fully recover, physical rebuilding must go hand in hand with psychological healing. The school needs more than bricks and books—it needs trauma support for students and teachers alike, consistent government attention, and long-term investment.

Paul Daji is hopeful, but realistic.

“We’ve survived Boko Haram. But survival is just the beginning,” he says. “Now we need the world to remember us, not just when we’re attacked, but while we’re rebuilding.”

To improve school infrastructure, staffing, and essential equipment, the Governor Ahmadu Umaru Fintiri, in 2022 approved ₦883 million for the renovation of ten legacy secondary schools.

When our reporter visited GSS Shuwa in March, we confirmed the implementation of renovations funded by the ₦104 million allocation within the larger ₦883 million project. We also observed that 20 Global Services Limited, the contracted firm, had rehabilitated a senior secondary school classroom block, physics and chemistry laboratories, the school clinic, and the examination hall.

Dormitories left abandoned

While renovations have been carried out in the academic areas of the school, the boarding section remains incomplete. In fact, students do not sleep there due to the unrepaired burnt structures. “We have six boarding hostel blocks that were destroyed by terrorists and they haven’t been renovated. They still stand in ruins with no roofing,” Paul added.

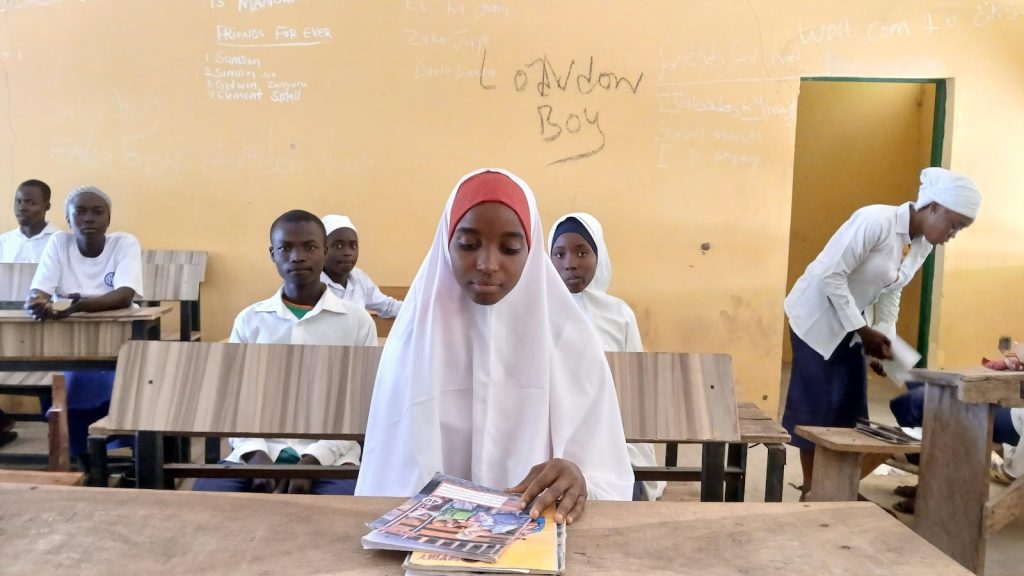

Meanwhile, the absence of a boarding facility deeply affects students. Maryam Ibrahim, an SS3 student, who struggles to study at home after school hours said “when I’m not in school, I’m always busy with household tasks and even if I decided to study, I do it with no supervision.”

Before the insurgence, her brother, Abdullahi, was also a boarding student. He spoke of evening and night group studies in the GSS Shuwa hostels which was a common practice over a decade ago. Now, there’s absence of this vital academic support and structured study time, and it is impacting the quality of students’ education.

Similarly, Hamman Samson, one of the school’s teachers, acknowledged that the absence of both hostels and teacher quarters, saying it has severely hampered the school’s ability to provide comprehensive support for its students.

He recounted that before the destruction by Boko Haram, teachers lived fully within the school premises, enabling them to engage in students’ night preps. But now, it has become an impossibility with the lack of hostels. With about 18 staff quarters burnt and abandoned, many tutors, like Hamman, are now scattered across Shuwa village, temporarily lodging with locals either for free or paying rent. Others commute daily, spending up to ₦1,000 for 30-35 minutes trips to and from the school.

“My family lives in distant Yola. I can’t keep my family here,” he said. “There’s nowhere for them to stay, and it’s not safe. We are hoping that the staff quarters will be renovated alongside the boarding hostels. That will make us happy because when all the staff and students are here, academic activities will run smoothly.”

More challenges

Emmanuel Achaba, the vice principal of administration at GSS Shuwa, does not trust that the rebuilt structures will hold for too long if there were to be any new attacks. He believes the materials used in rebuilding were substandard, explaining that whenever it rains, the roofing leaks water. This, he said, is not conducive for learning.

He also highlighted that despite the rehabilitation efforts, the school still faces a shortage of seats. “The school management had to seek donations from individuals and the Parent Teachers Association (PTA) to procure some chairs, but the number remains inadequate,” Emmanuel said.

The whiteboards and markers, which teachers should be using, are also not available. Our reporter discovered that the school also faces critical water and sanitation problems. The only hand-borehole available provides water that some students like Nathaniel John, the school’s head boy, consider not potable for drinking due to its unpleasant taste.

The school once had solar-powered boreholes where students would gather to drink water, but they are now broken and need repair. Similarly, Rachael Yohanna, another student, reported that the school lacks standard toilets, as the few available are in disrepair.

“It’s really bad with the toilets here,” Rachael lamented. “We have just one toilet for everyone, and students often leave it dirty with faeces. In this situation, many of us end up having to go to the bush to relieve ourselves.”

Efforts to get comments from the Adamawa State Commissioner for Education and Human Capital Development, Garba Umar Pella, regarding the infrastructural challenges, proved abortive. He was said to be away on official duties during our reporter’s visit to his office.

However, a staff member in the finance and supplies department of the Ministry, who refused to disclose his name, admitted that the Ministry is aware of the challenges and is collaborating with other education development partners to address them. “We are currently working on the estimates for how best the renovations can be carried out,” he said.

‘We are still living in fear’

Hafsat Bajjo, a 17-year-old student, has been at GSS Shuwa since her JSS1, which started in 2019. Although she was in primary school in 2014 when Boko Haram started wreaking havoc on Shuwa, the memories are still etched in her mind, especially the struggle her family experienced with fleeing to Yola for safety.

“We stayed in Yola for two years until 2016, when we returned to Shuwa, and I continued school. In Yola, I stopped going to school completely, and that affected my interest in school when we came back to Shuwa,” Hafsat narrated.

Now, in SS3, Hafsat still feels scared about potential attacks to her school or even on the Shuwa town entirely. She hopes that she will be able to write her O’level examinations successfully and go far away from Shuwa for her degree programme.

Amid the fear, the principal, Paul, assured the students that they will be protected as the management of the school had used PTA funds to hire four vigilantes for school security.

But Bitrus Tumbava, the vigilantes’ head, said that working as a security guard is challenging, given the school’s large size and their local hunting guns are insufficient against rifles wielded by Boko Haram members.

“We are still committed to our work despite the fear of Boko Haram attacks. This school is for our community, and we are responsible for the students’ safety. So, we are trying to ensure no harm comes to them here,” Bitrus said. He added that there have been no direct attacks on the school since he began working two years ago but the hoped for effective firearms like AK-47 along with sufficient bullets to truly safeguard the students.

Paul believes that even with more vigilantes carrying more powerful shotguns and increased military presence, the traumatic events of the past still haunt them and uncertain of the future.

“Not more than two weeks ago, there was another attack in Hyambula (a village near Shuwa) where one of the vigilantes lost his life. The Nigerian military has been trying to respond to the attacks, but honestly, news like these frightens us,” Paul said.

This report is a collaboration between Social Voices and HumAngle under the 2024 HumAngle North East Accountability Project and was first published by HumAngle.

In March 2014, Boko Haram fighters attacked Government Secondary School, Shuwa in Adamawa, Nigeria, causing chaos and fear and leading to school closures and community displacement. Despite being reclaimed by Nigerian military forces in 2015, the school struggled to resume operations, facing infrastructural damage, lack of staff, and absent family from the area.

Renovations approved in 2022 have begun rebuilding essential infrastructure, yet challenges remain, including unsafe dormitories, inadequate facilities, and ongoing fears due to past insurgencies.

Security measures have been implemented, but the legacy of trauma lingers for students and staff alike.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter