The Working Realities Of Nigeria’s Female Lawyers

Nigeria is experiencing an increase in the number of women being called to the bar each year, but what happens to these women in legal practice? Our research shows that it is significantly harder for women lawyers to excel in the field due to the gender pay gap, sexual harassment, and the cultural belief that women cannot perform as well as men.

When Damilola Bakari,*28 , decided to pursue a law degree abroad, she was not sure about the kind of lawyer she wanted to be. For one, the burnout she experienced at the university left her discouraged about the profession. What she did not know was that the worst was yet to come out there.

“I didn’t even want to go to law school when I came back [from university] but my father forced me to and law school was even harder than University. I discovered the picture I had of law was totally different from what it was in practice but I still gave it my all,” she told HumAngle.

While in law school, Damilola underwent her externship in a law firm. But even that was not enough to prepare her for the corporate legal world, especially as a woman.

The externship programme is a part of the Nigerian Law School curriculum where students are made to undergo out-of-classroom training – the first part is the four-week courtroom attachment followed by the six-week law chamber attachment. Afterwards, they return to school to take the bar exam.

After school, she began to look for opportunities at law firms. During the interview stage of securing her current job, she saw some troubling signs.

“During the interview, I was taken aback when the person asked me if I expected a salary for the job. I was too shocked to reply,” she narrated.

Damilola thought her professional career would be enough to live on. She feels the payment she gets as a practising lawyer in the big law firm she works is dehumanising, but there are few options for her.

“I think apart from the lack of adequate pay, the worst part of it for me is how I am treated as a female lawyer not just by the firm itself but even by clients. Sometimes, we will have clients assume that we are incapable of handling an issue or try to mansplain our job to us even if they have no basic knowledge of the law,” she said. Once, she had a client demand a male lawyer.

But the struggles do not end there.

According to Article 15 (2) of the 1999 Constitution, discrimination on the basis of sex and gender is prohibited and provides that men and women should have equal access to the courts in torts, contracts and all civil matters. And Article 17 (1) and (2) recognises women’s equal rights, obligations and opportunities before the law.

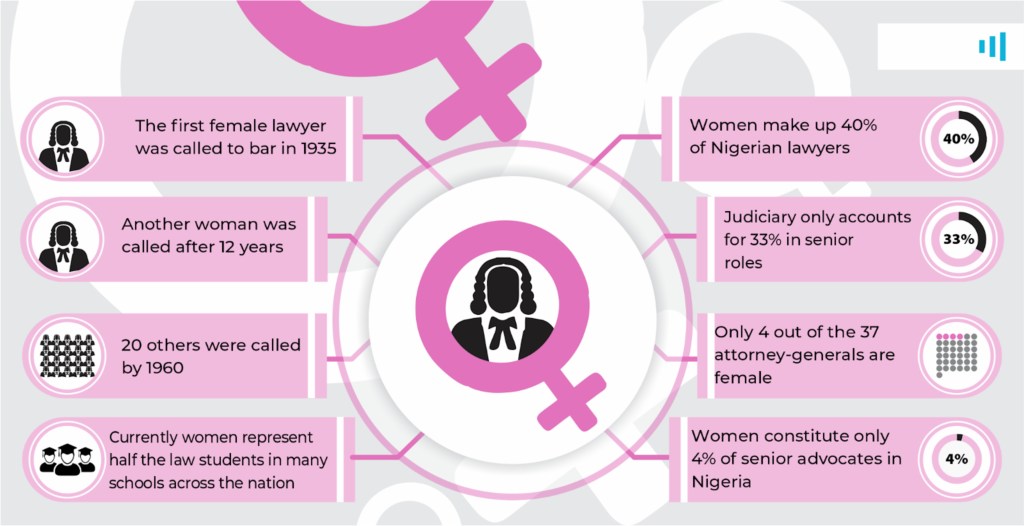

After the first female lawyer, Stella Jane Marke, was called to the bar in 1935, it took 12 years before another woman was called and by 1960, there were only 20 women called to the Nigerian bar. But women currently represent half the law students in many schools across the country.

However, according to the ’50:50 By 2030’ gender report by the International Bar Association and LexisNexis Rule of Law Foundation, women make up 40 per cent of Nigerian lawyers, but the judiciary only accounts for 33 per cent of women in senior roles, with law firms having only 43 per cent of women in senior roles. Only 4 out of the 37 Attorney-Generals in Nigeria are female and women constitute only 4 per cent of the Senior Advocates in the entire country.

Sexual harassment and the pay gap

“There are times when clients text us after work and try to start a personal relationship with us, most times disrespectfully,” she continued.

With all this pressure, Damilola constantly finds herself anxious about how she is perceived when she is working. “I try not to smile too much or be too friendly to avoid miscommunication from both senior colleagues and clients alike.”

Women lawyers are usually forced to walk on eggshells during work hours so as not to be blamed for any immoral action committed against them, she explained.

A common problem that plagues her and some of the women lawyers she speaks to is when the senior lawyers use younger women lawyers’ vulnerability and commit acts of sexual harassment against them, making it harder to work in such a toxic environment. “And everyone just turns a blind eye and pretend they don’t see it happening. It doesn’t help that there is no Human Resource department in my office to report to. So the female lawyers just try to keep their distance, but it doesn’t save them.”

A 2016 report by Equal Enforcement Opportunities Commission (EEOC) states that 60 per cent of women confirmed to have experienced sexual harassment in the workplace. This impacts both the victims and the society, leading to issues like decreased work performance, hostile behaviour in work environments, feelings of shame and guilt as well as an increase in the rate of absences from work.

When she started working in the firm, the women were not given many cases. The men had the advantage and this made it difficult to argue about a gender pay gap when the women had fewer opportunities to prove themselves.

“Once, a senior lawyer was looking for someone to draft a letter but only gave it to a female lawyer when he couldn’t get a male lawyer to do it. It felt like we were hired to be redundant and when you try to do something, the environment becomes even more hostile,” Damilola said. When she speaks to her other lawyer friends, she realises that it is more common than she thought.

Even though Article 11 of the 1999 constitution provides that women should have equal rights as men regarding the choice of profession, employment opportunities, remuneration and promotion, there is an issue of gender bias that clearly makes it harder for women to earn as much as their male counterparts by deliberately keeping them away from opportunities. According to a study done in Malawi, Nigeria and Tanzania, women earn about 40-46 per cent less than men in urban areas and the gender pay gap in Nigerian rural areas is around 77 per cent.

“Sometimes, they give the excuse that some cases are too serious to be given to newbies, but if they don’t give us any work it makes it harder for us to learn. The only person that tries in that regard is our head of chambers but he is not always around to ensure we get work done.” And Damilola is not the type of person who believes in sitting in the office doing nothing.

Once, a case was given to Damilola and another female colleague. After doing everything pertaining to it, a senior lawyer took the file because the case had been reassigned to him due to a minor issue that could have easily been handled.

“The payment also isn’t enough and nothing motivates you. I feel that’s why a lot of young female lawyers are leaving for other professions.

“I recently spoke to a friend who quit her job in a law firm due to similar issues.”

Damilola’s office had refused to sign women like her as permanent employees and has paid them the same measly salary since 2021.

But despite all these issues, Damilola does not want to give up on law practice completely. “I am tired of legal practice and I want to try other things at the moment, but I think I will eventually come back to law, even if I don’t end up coming back into litigation,” she concluded.

Losing interest

Sadiya Munir*, 25, was posted to Kaduna State for her National Youth Service Corps. She had two law firms to choose from and decided to go with the one closest to her house mostly because they had a payment option that the other law firm lacked.

“I came to Kaduna all enthusiastic about litigation but things didn’t go as expected,” she began. In her first week at work, she noticed the female lawyers had almost nothing to do.

“I assumed that maybe it was because the year just started and there wasn’t much work to do.” But the problem persisted for the ten months she was there.

“We have about three male lawyers and seven female lawyers and, even though they are overworked they still prefer them over us.”

Sadiya and her female colleagues usually find themselves assisting the male lawyers with their duties, such as announcing appearances in court and other minor tasks despite the fact that both genders overcame the same obstacles and wrote the same exams to get there.

Also, the office has benefits for employees such as free lunches but the burden of serving the male lawyers lies on the shoulders of the female lawyers. “I could remember once, a senior lawyer saw one of the male lawyers serving himself food and asked him what he was doing in the kitchen as a man instead of getting one of the women in the office to handle that,” she said.

Gender stereotypes such as the belief that women are caring nurturers and men are dominant providers perpetuate sexism in the workplace by limiting people to presumed roles instead of focusing on their individual strengths and weaknesses. However, there is no evidence that shows differences in how women’s and men’s brains are wired and emphasising these stereotypes only makes it harder for women to navigate the workplace.

“I haven’t moved a motion or done anything of substance since I came here. I will soon be leaving and I can’t wait to go,” Sadiya said. She was asked by one of the partners if she wanted to be retained but she rejected the offer. “I can’t waste all the years I spent studying law sitting in the office, serving food and watching TV.”

She added that as a prestigious law firm, they take pride in how much they empower women by the number of female employees, but this is without prospects. To make matters worse, the payment is not enough to cover her expenses.

“I get paid ₦15,000 monthly (less than $15) and I constantly feel left behind and it affects me psychologically.” Sadiya worries about what that will mean for her future and feels discouraged about furthering a career in law.

According to a study sponsored by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, sexism creates an environment where women are likely to underperform and have a harder time succeeding at work due to the fear that their work will confirm negative gender-based stereotypes.

“I am currently looking into other options like human resources. I want to take online courses and I have an internship next year in another field. I do want to stay close to law but I have lost interest in litigation.”

Asterisked names are changed to protect identities

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter