The Unsettling Data On Child Education In Northeast Nigeria

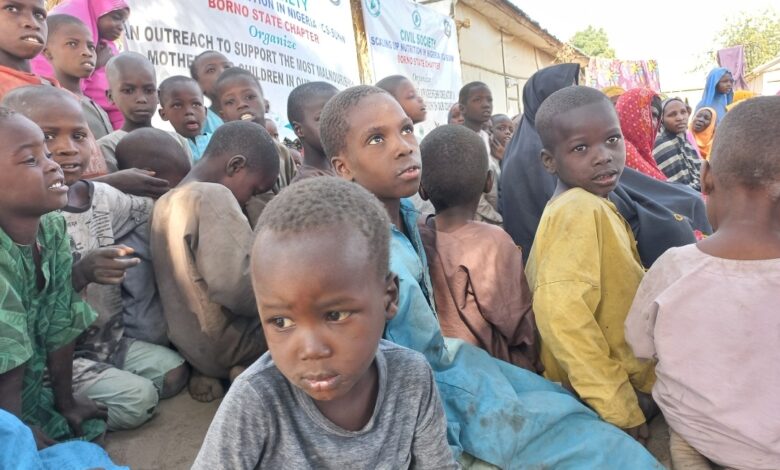

Thousands of children affected by the Boko Haram insurgency in Northeast Nigeria are still out of school in key states of the subregion despite efforts by government and humanitarian agencies.

The United Nations Children Fund, UNICEF, has said that more than 1.9 million children have been affected by the 13-year-long armed conflict in Northeast Nigeria.

The conflict, which has uprooted millions of people from their original homes, has left 1.3 million conflict-affected boys and girls without access to primary, quality education.

Quoting the most recent data, UNICEF said 430,000 children affected by the Boko Haram conflict have no access to education. In contrast, about 167,000 of them were similarly affected in Yobe state.

UNICEF said 56 per cent of displaced children across the BAY states still do not attend school.

According to the UN’s main intervention body, “Children in Borno State are among the most conflict-affected and educationally disadvantaged in the world.”

It is on record that since 2009, over 1,400 schools have been destroyed and 2,295 teachers killed across the North-East as a result of the Boko Haram crisis.

UNICEF, in a 2021 report, blamed “Attacks by armed groups on education and school facilities, the influx of internally displaced families into metropolitan cities, and population growth” as some of the negative factors that also stretched existing school structures to the limit, creating challenges of access, retention, and school completion.

But these attacks on schools persist years after the UN launched 30 million dollars on Nigeria’s Safe Schools Initiative in April 2014.

When the Safe Schools Initiative, the UN Special Envoy for Global Education, Mr Gordon Brown, described the initiative as “a novel idea.”

The former UK Prime Minister had at that time said the program would ensure “every girl to be safe and boys also to be safe when they go to school but mainly girls.“

He added that “The Safe Schools Initiative is designed to help fortify the schools and also help the telecommunications between the schools and prevent the attacks.”

But nine years down the line, children still find it unsafe to go school.

Even in camps where an organization like UNICEF supports kids in displacement to attend classes in makeshift schools, the parent still laments how their kids spend most of their time playing due to a lack of teachers.

In a report published by HumAngle, some parents lamented how teachers hardly show up in classes provided by UNICEF in camps.

“Our children would wake up as early as possible to be in classes only to end up using the entire class hours for playing and running around,” Abba Mustapha, an IDP in Muna Alamdari camp, once told HumAngle.

“Unicef provided the learning centre for us, but no one cares for the pupil, which worries us a lot.

“Over time, some of the parents became discouraged seeing that their children were not getting any lessons but rather playing all day only to return home hungry, so they decided to stop them from attending classes,” he said.

It isn’t very comforting to note that one in every three children in the NE is out of school.

The UNICEF report indicated that only 29 per cent of schools in the BAY states have teachers with the minimum level of teaching qualification.

The average pupil-teacher ratio across the BAY State is 124 to one.

Scarce Teachers

A “study published by the United Nations Children’s Fund in 2017 shows that over 2,295 teachers have been killed and 19,000 displaced in the Northeast since the Boko Haram insurgency started in 2009.” The lack has gravely impacted the quality of learning the children get, even in the makeshift schools provided by the humanitarian organizations in the IDP camps and some host communities.

HumAngle spoke with some parents who expressed their frustrations with the nature of the education provided for their wards in the camp.

“Our children would wake up as early as possible to be in classes only to end up using the entire class hours for playing and running around,” Abba Mustapha, an IDP in Muna Alamdari camp, said.

“UNICEF provided the learning centre for us, but no one is there to care for the pupil, which worries us a lot.

“Over time, some of us became discouraged seeing that our children are not getting any lessons but rather play all day only to return home hungry, so some of us decided to stop them from attending classes,” he said.

The recent report also revealed that “around half of all schools require rehabilitation (47.3%)…and only 30% of schools have sufficient learning materials in Adamawa, with lower proportions in Borno (26%)

and Yobe (25%).”

Despite the interventions by UNICEF, the report said only 47% of schools in Borno have fine furniture, with lower proportions in Yobe (32%) and Adamawa (26%).

“Fewer than half of schools (46%) had access to adequate and safe drinking water, with an average of 262 students per latrine.”

UNICEF has however launched a training programme for teachers to fill the gaps, by training thousands of teachers so far, but the government needs to have a deliberate and holistic strategy to address the devastating impact of the Boko Haram conflict on education.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter