The Unending Attacks Strangling Life in Benue-Cameroon Borderlands

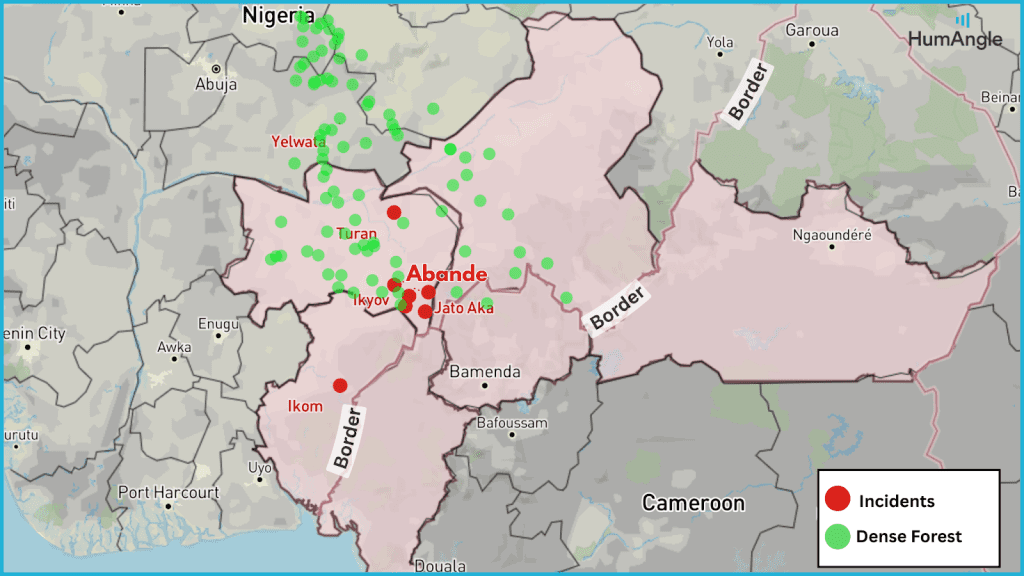

In Benue’s borderlands with Cameroon and Taraba, repeated attacks by armed groups have erased villages, emptied markets, and exposed a deadly vacuum where security should be.

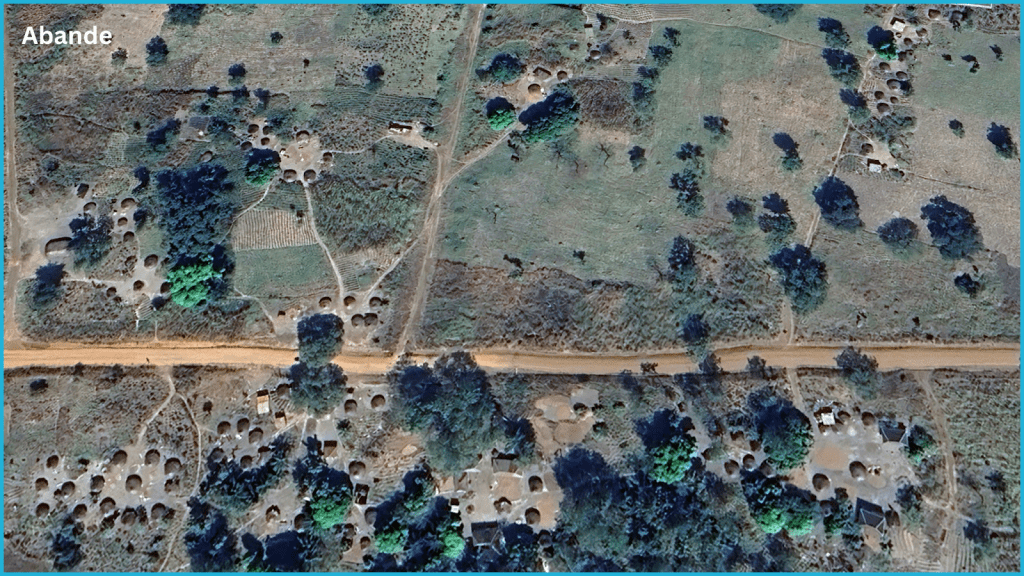

The terrorists struck on a day the people of Abande know by heart.

Every five days, the settlement in Mbaikyor Ward, Turan district, hosts a market that draws traders from across Benue State, in Nigeria’s North Central, neighbouring Taraba State, and the Republic of Cameroon, which is less than a day’s walk away. Abande Market is where goods are exchanged, relationships renewed, and livelihoods sustained.

On Tuesday, Feb. 3, it became a killing ground.

As traders arranged their wares and customers haggled over prices, terrorists stormed the market, opening fire on civilians and setting stalls, nearby homes, and other properties ablaze. The attack sent traders and buyers fleeing in all directions, leaving behind goods, livestock, and the dead. By the time the terrorists withdrew, the market had turned into a scene of bloodshed and ruins.

“I lost everything in the fires,” one trader said.

Police authorities noted that at least 17 people were killed. Others remain missing, Antipas Shomwua, a local security analyst, told HumAngle. “It is so disheartening,” he said. “The damage is much.”

Benue State Governor Hyacinth Alia, who confirmed the incident, described it as “a cowardly act of terror” that claimed innocent lives, including that of a police officer. He said the attack was an affront to the state’s peace and security.

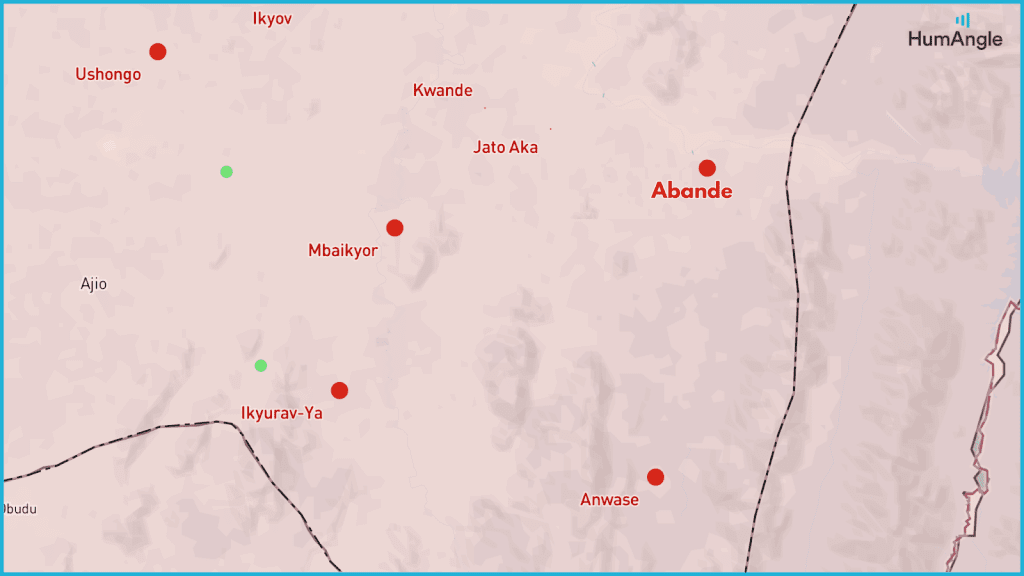

For residents of Kwande Local Government Area, where Abande is situated, the attack did not feel like a sudden escalation. Instead, it felt like another chapter in a story they say began more than a decade ago and has never truly paused. Locals who spoke to HumAngle believe the attackers are armed herders who have repeatedly targeted communities in the area since 2012.

One resident, who requested anonymity for fear of reprisals, said the attacks began when armed groups, who disguised themselves as herders, entered through the Taraba border and struck villages, starting with a community called Ikyo-awen. “People were displaced, the community was taken over,” he said. “Since then, the attacks have continued from bases behind the hills that separate the Turan district communities.”

The hills he referenced are a recurring feature in residents’ accounts of the violence. They form natural boundaries between communities, but, according to locals, also serve as cover for attackers who strike and retreat beyond easy reach. Over time, this geography has contributed to a sense of vulnerability among residents, who say attacks often come without warning and end without accountability.

According to local leaders and residents, the violence is inseparable from the geography of the Benue–Cameroon and Taraba borders and what they describe as the state’s long-standing failure to secure it.

Terseer Ugbor, the House of Representatives member representing the Kwande/Ushongo federal constituency, said the area is effectively left exposed. “The closest security post to Kwande is in Ikom, Cross River State, in the South South — over 400 kilometres away,” he said. “From Ikom all the way through Benue, Taraba, and Adamawa, there is not a single checkpoint up to Nigeria’s border with Cameroon.”

Terseer said this absence of security infrastructure has turned the borderlands into a corridor for armed groups, enabling them to move in and out of communities with little resistance. The hills and forests that form natural boundaries between Turan district communities, neighbouring states, and Cameroon are said to provide cover for attackers, who strike and retreat beyond the reach of local security forces. Over time, this has deepened a sense of exposure and abandonment among communities that feel caught between borders but protected by none.

“The terrorists have found a loophole in our security architecture,” Terseer said.

Federal authorities have acknowledged the risks posed by Nigeria’s porous borders, but affected communities say such recognition has yet to translate into visible protection on the ground. After a similar massacre in Yelwata, another Benue community, in June 2025, Christopher Musa, then Chief of Defence Staff and now Minister of Defence, conceded that border control remained central to addressing the violence, noting that “the borders are critical to the work we are doing [in securing the communities].”

For residents of Kwande, however, the continued absence of checkpoints, patrols, or permanent security formations suggests that these vulnerabilities remain largely unaddressed.

This gap between official statements and everyday insecurity shapes how the violence is understood by the residents. It is why they resist descriptions of the killings as communal clashes, insisting instead that the pattern of attacks points to something more organised and deliberate. “This is terrorism,” Ordue Aondoakaa*, a Kwande native, said. “They kill us and occupy our land.” He contrasted the situation with what he described as typical farmer–herder clashes, which, in his view, are often addressed through local dialogue and town hall meetings. “If it were a communal incident, it would have been resolved,” he added.

This distinction matters deeply to residents. Being labelled as communal violence, they argue, diminishes the scale and intent of the attacks and allows them to be treated as routine conflicts rather than as organised campaigns of terror. For communities that say they have lost land, homes, and entire villages, the language used to describe the violence shapes whether they are seen as victims of insecurity or participants in unresolved disputes.

In the aftermath of the latest attack, women and children have fled Abande and surrounding villages, seeking safety in Jato-Aka, a major town in the local government area. Their flight mirrors earlier waves of displacement that have hollowed out once-thriving communities along the border.

According to the United Nations’ International Organisation for Migration, more than 15,909 internally displaced persons were registered in Kwande as of November 2025. Among them are district heads who have been unable to return to their communities for over a decade. “Of the five council wards in Turan, only two have not been affected by these terror attacks,” the local said.

Abande lies close to Anwase, another community in Mbaikyor Ward that was attacked on Dec. 24, 2024, and again in March 2025. Several other communities in the ward and neighbouring ones have also come under repeated assaults, gradually erasing social and economic life across the area.

“Abande Market is one of the only surviving markets in the ward,” a local trader told HumAngle. “All the others, where people used to buy honey, palm oil, and other farm produce common here, have shut down.”

Any fragile sense of recovery was short-lived. Just three days after the Abande massacre, the attackers returned to Anwase. On Feb. 6, terrorists struck Anwase Market, killing 13 people and abducting several residents, especially women.

“It is the same pattern and the same people,” a local said.

During an operational visit to Abande, a day before the attack in Anwase, DCP Okon Asuquo, the Head of Operations at the Benue State Police Command, said, “I want to assure the people of Abande that their lives and properties will be secured.”

Despite statements from security authorities and the state government assuring residents that “such attacks are decisively prevented,” the latest incident in Anwase suggests otherwise, raising questions about the effectiveness of reinforced security measures.

“People are helpless and without defence,” one trader in Jato-Aka told HumAngle. “When Abande was attacked, only three police officers were stationed at the entire market; one of them was killed. That was Abande. In many other places, there is no security presence at all.”

Schools, healthcare centres, markets, and other socio-economic activities in the district have been closed down. Across Kwande Local Government Area — as in other parts of Benue — affected communities have increasingly relied on local vigilantes, even to escort the bodies of loved ones back to deserted ancestral homes, fearing further attacks along the way. HumAngle reported on this extensively in June 2025.

Terseer, the federal legislator, has called on the state government to “provide logistical support and accommodation for the activation of the Border Patrol Unit already approved by the Inspector General of Police for the constant patrol of the Turan and Ikyurav-Ya border areas with Taraba State and Cameroon”.

He also said that this should be followed by a total ban on illegal mining activities, the construction of resettlement homes, hospitals, and schools for displaced persons in the area. “I firmly believe that the sincere and comprehensive implementation of these recommendations will bring lasting peace to Kwande,” Terseer added.

*Names marked with an asterisk are pseudonyms used to protect the identities of the sources.

On February 3rd, the Abande Market in Mbaikyor Ward, Benue State, was attacked by armed terrorists, resulting in at least 17 deaths and widespread destruction. Governor Hyacinth Alia described it as a cowardly act of terror, exacerbating a long-standing cycle of violence attributed to armed groups disguising as herders from across the porous borders with Taraba State and Cameroon. The geography and lack of security checkpoints in the region provide cover for attackers, leaving residents feeling vulnerable and exposed, intensifying the pattern of organized attacks rather than communal clashes.

The atrocities in Abande and surrounding districts have led to massive displacement, with schools and hospitals closing and residents relying on local vigilantes for security. There are calls for government action to secure the borders, ban illegal mining, and build infrastructure to house displaced individuals, aiming to restore peace to the troubled region. Despite assurances from authorities, the continued violence, including a recent attack in Anwase, highlights the ineffective security measures and lack of protection for the vulnerable communities.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter