The Tradition Of Tribal Marking In Southwest Nigeria And Why It’s Fading

One of the first things noticeable about Segun is the tribal marks on his light-skinned face. He used to detest the thick, dark lines but has increasingly accepted them as part of his identity. “I have no choice but to live with them and no longer have resentment towards my parents for giving me such scars,” he said.

While schooling in the northeastern part of the country, he faced a lot of stigma as a result of his marks and cultural difference. He recalled that he was “an object of ridicule” and often felt dejected.

Before now, tribal marks meant different things to different people and tribes. They are a prominent part of Yoruba culture and are usually inscribed on the body by burning or cutting the skin during childhood. The primary function is to identify with a particular tribe, family, or patrilineal heritage. Some of the common marks are those associated with Ile-Ife, Oyo, Ogbomoso, and Egba ethnic groups.

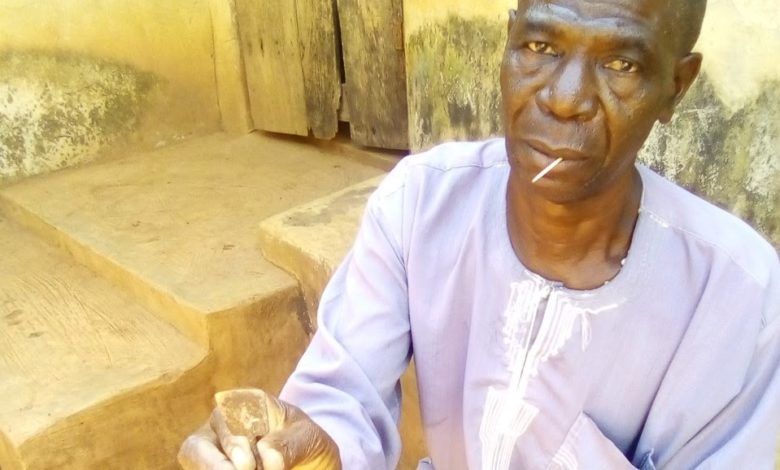

HumAngle visited the Oloola-Oke household in Oyo State, famous for making scarifications. The head of the family, Mustapha Oloola, disclosed that he started learning by observing and serving senior family members at a young age as they scarified the cheeks of willing clients.

“The identity of our people could be known from Gombo or Keke styles which comprises straight and curved lines made on the side of the mouth and peculiar to our people,” said Oloola.

“In the days of my own grandparents and great grandparents, incisions were used for medical purposes as well. Incisions were made on the faces of children or any part of the body where there was an ailment.”

The illnesses whose cures were sought through incisions, laced with medicine, included convulsion, pneumonia, and measles. Ila abiku (marks for children who died before reaching puberty) were also administered to prevent premature deaths.

Explaining further, Oloola said, the practice of tribal marks and body incisions have contributed to cultural consciousness in Yoruba communities in Nigeria’s southwest. “Additionally, it was a source of aesthetic beautification and protection therapy through some spiritual and religious practices,” he said.

Asked what safety measures are taken during the incision, Oloola replied that the instruments were specially designed for the purpose of scarification and “precautions were taken to get the best”.

“Our forefathers believed that the instruments were protected against all diseases by God although those days such diseases as HIV/AIDs and other deadly infectious diseases were not rampant,” he, however, added. “No special preventive measures were taken because most of us who carried out the act trained and were always ready to go through the procedure.”

The practice of administering tribal marks is fading in various Yoruba communities, and one of the reasons for this are laws enacted by the government.

The Child Rights Act, domesticated by all states in Nigeria’s south, for example, states that “no person shall tattoo or make a skin mark or cause any tattoo or skin mark to be made on a child”. Violations of this provision would attract a fine, a term of imprisonment for a maximum of one month, or both.

So what does the Oloola-Oke family do for a living considering that getting tribal marks is no longer a norm? “We do special incisions for ladies occasionally and, once a while, circumcisions for males,” replied Alhaji Mustapha Oloola.

Asides the shame experienced by those with tribal marks later in life, another reason the practice is becoming outdated is the medical risks it poses if done by non-professionals.

A health practitioner and consultant with the Bowen University Teaching Hospital, Dr O.O. Abiola, completely discouraged making incisions or any traditional cuts, describing them as dangerous if done with unsafe instruments.

“The act of making any incision should be made with sterilised equipment to prevent the spread of illness, infection and diseases,” he explained.

“Depending on what is left on the instrument, this may also mean the spread of serious illness or diseases such as HIV/AIDs, Hepatitis, and many others. This could lead to patients becoming very ill and requiring further medical attention. Healthcare equipment, if not sterilised, could be a reservoir of pathogenic microorganisms, which can cause contamination and give rise to infection if not properly managed.”

In a telephone chat with Dr Isaac Bot, a medical practitioner at Vom Christian Hospital, Jos, he agreed that incisions could lead to serious infections if done with unsterilised equipment or not carried out by trained professionals.

“Any surgical issue must be referred to a standard hospital to avoid the risk of over-bleeding and contracting strange infectious diseases,” he stressed.

While a lot of parents are now determined not to scarify their children, many adults still have to live with this reality.

Akinola, 48, a tailor and resident of Ibadan who was given prominent tribal marks at birth, told HumAngle they have been a source of ridicule for him since his primary school days. The same goes for 32-year-old Yemisi whose face carries large Gombo marks depicting royalty.

“I suffered shame, embarrassment at the early stages of my life, but now my large tribal marks serve as an identity because people describe my shop using them,” said middle-aged Iya Bisi, a vendor resident in Taki, Oyo State.

“The years of shame are gone. Now that I am a grandmother, I made sure none of my children or grandchildren has a cut on their face or body in the name of tradition.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter