People in the car threw up due to the stench from the black plastic bag. It was a long journey through Gombe State in North East Nigeria, and because it was 3 a.m., at every checkpoint, soldiers would ask why they were travelling at such an ungodly hour. When they explained they were transporting a snakebite victim to the hospital in a nearby town, the soldiers would ask for proof.

The black plastic bag was proof. It was heavy from the weight of a dead, stinking snake. As soon as they were shown, the soldiers would hurriedly wave the car off, scrunching their noses, and wishing them luck.

Antu had started to lose consciousness in the back seat at this point. The pain was unbearable, and she wished she could detach her leg from the rest of her body. Everything was becoming blurred and distant.

The bite

Earlier that night, at around 1 a.m., it had started to rain. Antu stepped out of her room to retrieve her children’s uniforms, which she had spread outside to dry. As she stood with one foot inside and the other outside the living room, she felt something like a rope wrapped tightly around the leg that was inside, followed by a sharp prick. When she raised the leg, it felt heavy. When she hit it on the floor, something fell with a thud. She rushed into her room, grabbed a torchlight, flashed it and saw a snake.

“My children were all fast asleep in the living room, and the snake was right there in front of them. It was either I killed it or it killed me.”

Her husband lay in the room, half his body paralysed from a stroke, unable to help. Antu quickly tucked the flashlight into her headscarf and tightened it. She took a wooden stick from her broken drawer and struck the snake with it. It coiled around the stick. She slammed it against the floor. Then again, and again until the snake fell off, then she smashed its head with precision.

Once she was sure the snake was dead, she rushed out to shout for help, but the heavy rain drowned her voice. Blood was dripping from her leg; she had to think fast.

“I went into the room, carried my husband, brought him outside, and began bringing out the children one by one. There was a shabby fence between my house and the neighbours’. I kicked it until it broke down, then I sent my eldest daughter through it to knock on their door. When they opened, I took my children and husband inside.”

Antu explained the situation to her neighbour and said she was off to find medical treatment. The neighbour’s daughter accompanied her to a nearby clinic, but they were told the clinic couldn’t handle the case and were directed to the General Hospital. The driver who offered to take her there asked her to bring the snake. She returned home, picked it up, and put it in a black plastic bag.

“When we got to the General Hospital, they said they couldn’t treat me, that it was a case beyond their expertise. They identified the snake as a viper. An aged one. Then, they told us to rush to Kaltungo at once.”

So, they set out for Kaltungo from the town of Gombe.

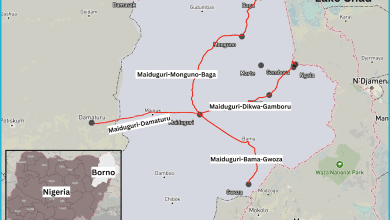

Kaltungo

Kaltungo is a local government area in Gombe, North East Nigeria, surrounded by rolling hills and scattered trees. Its mountainous topography encourages the growth and proliferation of snakes, which is why there is a prevalence of snakebites in the area. The most common species in Kaltungo is the viper, and for decades, it has cohabited with the townspeople.

The widespread occurrence of snakebites led to the establishment of the Snakebite Treatment Hospital and Research Centre in Kaltungo.

In the past, the Gombe State Government collaborated with the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine to research improved snakebite management methods. Snake samples were collected and sent to the institution to help create a programme focused on training personnel, providing essential equipment, and producing antivenom. However, the programme eventually faced challenges and was discontinued.

“The state government has since embarked on expanding the facility with the aim of improving snakebite treatment and producing antivenom locally,” Dr Habu Dahiru, Gombe’s Commissioner of Health, tells HumAngle.

“The antivenom is provided free of charge. The state government is the primary supplier and has recently received support from the Northeast Development Commission. We are calling on more partners to assist Gombe State in securing adequate antivenom, especially during peak periods when we stock up in advance.”

In the past six years, from 2019 to 2023, the hospital has recorded 13,306 cases of snakebites — with a mortality rate of 1.5 per cent. Fifty per cent of the victims were men, 22 per cent were women, and 28 per cent were children.

Still, across the country, roughly 2,000 people die every year from snakebites, according to Nigeria’s former minister of state for health, Olorunnimbe Mamora. About 1,700 other victims have their limbs amputated. After Gombe, states with the highest cases of snakebites are Plateau, Adamawa, Bauchi, and Borno.

Snakebite envenomation is regarded by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a Neglected Tropical Disease, an infection affecting impoverished communities in tropical regions, causing significant health, social, and economic harm.

Men in Kaltungo are often more susceptible to snakebites as they are predominantly farmers. Many get bitten by snakes as they farm. Some get bitten at home, some in the market, some even at school.

In a bid to contain the rampant snakebite incidents, the Emir, Mai Kaltungo, waged war against the snakes. He announced monetary rewards for anyone who kills a snake and brings it to the palace. Farmers began to hunt down snakes, but this practice was soon halted after researchers warned that killing the snakes would affect the production of antivenom.

Recovery

The next thing Antu remembers is the sting of the anti-venom injection. They had finally arrived at the Snakebite Hospital and Research Centre, where she would receive treatment.

“I felt like snakes were writhing in my leg, threatening to break them,” she recalls. “I was shouting, ‘Please help me! They’ll break my leg!’”

The doctors explained that this sensation meant the antidote was fighting the poison. Antu spent a week in the hospital receiving treatment.

“The average recovery time in our facility is five days. Patients who come within 24 to 48 hours of a bite usually recover well,” Dr Nicolas Hamman, the Principal Medical Officer in the snakebite hospital, explains. “Most mortalities occur in patients who come late, often after trying traditional concoctions from multiple healers. By then, they usually have severe systemic envenomation, leading to complications or death.”

The day after Antu began her treatment, a group of foreign researchers who were visiting the hospital examined the snake. They expressed a keen interest in seeing Antu and assessing how the venom had affected her.

“They said the chances of surviving such a snakebite were slim, yet here I was, alive and speaking,” Antu says. “They even had an interview with me.”

After returning home, whenever her leg began to ache, she would call the doctors and describe her symptoms. They would advise her on what to do and assure her that it was part of the healing process.

“Rashes even broke out on my skin, and it started to peel,” she remembers.

Eventually, the doctors removed the snake’s fangs from her leg. It took three months for Antu to fully recover and return to her normal daily activities.

And now, four years later, especially on cold harmattan nights when her leg begins to ache, the memories of that rainy night still revisit Antu. She is grateful to God that she survived it, she says. She came out of the experience stronger, after all.

A woman named Antu in Gombe State, North East Nigeria, was bitten by a snake while retrieving her children's uniforms during a rainy night. Her harrowing journey to get medical assistance involved transporting a dead snake as proof of the bite through several checkpoints before finally reaching the Snakebite Treatment Hospital in Kaltungo, known for handling snakebite cases due to the region's high snake population.

Despite initial treatment delays and referrals to multiple hospitals, Antu eventually received anti-venom treatment and spent a week recovering in the hospital. Her survival was notable, given the severity of viper bites, and she experienced a lengthy recovery period of three months with ongoing painful symptoms. Her ordeal underscores the critical issue of snakebites in the region and the ongoing efforts to manage and treat them effectively.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter