The Risks That Come With Drilling Oil In Nigeria’s North

Beyond the fanfare, there are environmental, wildlife, and security concerns related to oil and gas exploitation in the Kolmani river field.

Nigerian authorities have announced the discovery of oil and gas deposits in the savannah drylands of the north amid a production drop in the Niger Delta. However, hydrocarbon exploration in the new basin could lead to environmental pollution, endanger wildlife, and be rocked by insecurity.

In November, President Muhammadu Buhari visited the Kolmani river field in the Upper Benue Trough between the northeastern states of Bauchi and Gombe. The discovery in the area, also known as the Gongola Basin, was first announced in Oct. 2019 after several previous attempts to find oil in the country’s north.

“We are pleased with the current discovery of over one billion barrels of oil reserves and 500 billion cubic feet of gas within the Kolmani area and the huge potential for more deposits as we intensify exploration efforts,” Buhari was quoted as saying.

It is not clear when production will commence in the field. However, the licence area is categorised as Oil Prospecting Lease 809 and 810, meaning it is still in the stage of exploration and appraisal.

After investigations are concluded, oil mining licences could be granted, paving the way to full-scale production. Authorities say the field would be utilised through an integrated development project, which has reportedly attracted foreign direct investment of about $3 billion and would host a refinery, fertiliser, gas processing, and electricity generation plants.

HumAngle obtained satellite images showing the gradual build-up of exploration activities in the basin over the past few years. The data highlights how the movement of heavy vehicles and the construction of facilities and support infrastructure has impacted the local environment.

The images show that the area has scattered trees with minimal human activities in the form of small clusters of compounds and farmlands, although more villages are visible much farther.

Between July 2017 and Dec. 2018, there was a rapid change in the geography with the appearance of a dirt road, a concrete oil well pad at a site, and earthwork taking place at another one less than a kilometre across a seasonal river. This build-up trend continued to increase in 2019 with the intensification of exploration and the setting up of operational infrastructure.

Visible on satellite is the expanding dirt road network for moving equipment and personnel between the sites and other locations. As of April 2019, work had escalated on the drilling site, with operators constructing multiple helipads and a temporary bridge in preparation for the rainy season.

The second site appeared to have become fully operational between May 2021 and February this year. At the same time, the first location was shut down while a concrete bridge was being constructed. The road was also tarred, indicating plans for extensive operations in the area.

Environmental and wildlife concerns

“We have learnt our lessons. With the developments and what has been happening around the Niger Delta and other oil-producing areas of the world, naturally, no government will allow things to follow the same track,” the Governor of Gombe, Inuwa Yahaya, noted in an interview about oil exploration activities in his state.

It highlights the concerns around protecting the environment and the need to avoid the widespread pollution that has continued to plague the Niger Delta in South-south Nigeria.

The prevention of spills and management of gas flares is essential. In 2019, Nigeria’s oil company said it would no longer sign off on gas projects that flare gas indiscriminately. It made a statement of intent that it is committed to a “zero gas flare regime”, but whether that means no gas flaring at all is not established.

Yankari Game Reserve is about 16 kilometres from the closest drilling site. The closeness of the oil field infrastructure to the game reserve further highlights the importance of mitigating an ecological crisis in the basin. The conservation sanctuary covers a total area of 2,244 km², and has a diverse and sensitive wildlife population, including elephants, lions, buffalos, and hippopotamuses.

The loud noises, human movement, and vehicle traffic from drilling operations can be a menace for the animals. The Gaji river that runs through it could also be affected when the exploitation of the field leads to more activities and pollution.

An environmental activist and founder of Surge Africa, Nasreen Al-amin, says any extractive activity within the axis of the Yankari Game Reserve threatens a very fragile ecosystem. She added that considering its importance as a biodiversity hotspot where many endangered species continue to thrive, measures are needed to protect the reserve.

The expectation is that the conduct of an Environmental Impact Assessment would consider the investment required to preserve and protect the natural environment. For example, in Uganda, environmental and conservation groups are opposing oil exploration activities in the country’s Murchison Falls Park.

The companies working to develop the oilfield have, however, made promises to reduce the impact of the development through smaller footprints, noise limits, buried pipelines, and elephant-proof fencing around work areas.

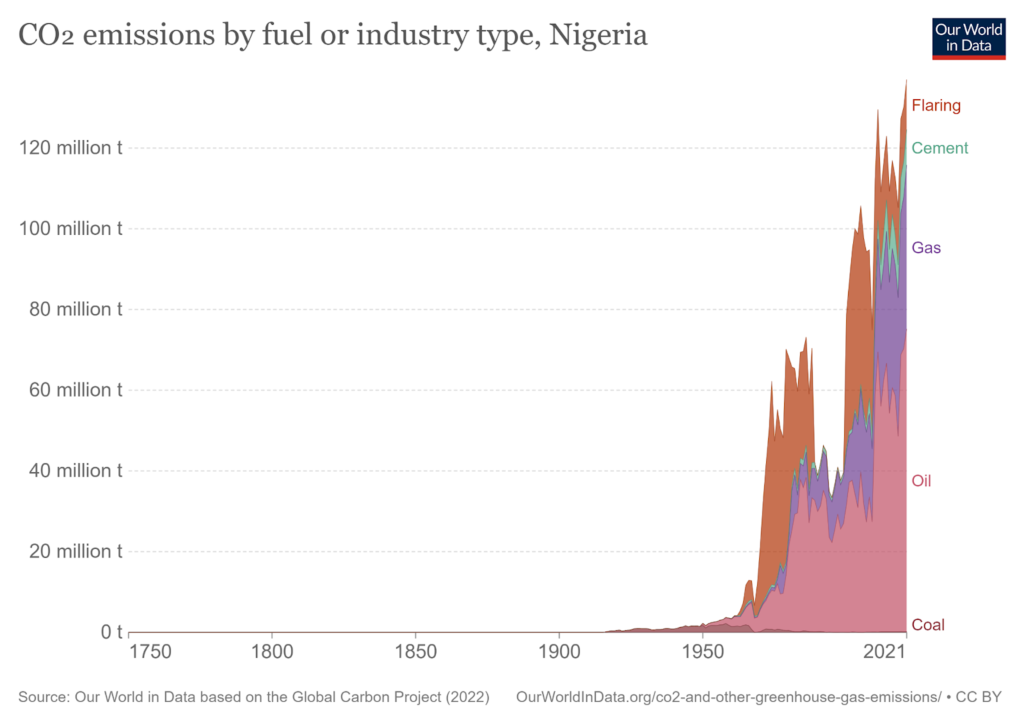

Apart from pollution and wildlife conservation concerns, the project could come under the spotlight of Nigeria’s energy transition and nationally determined contribution (NDC) targets.

Last year, the government committed to unconditionally reduce emissions by 20 per cent below business-as-usual by 2030 and to achieve a 47 per cent conditional reduction with international support.

Emission target

The global push to cut emissions and accelerate the transition to cleaner energy has impacted the availability of finance for new hydrocarbon projects. This is likely connected to the President’s remarks that “at a time when there is near zero appetite for investment in fossil energy, coupled with the location challenges, we are able to attract investment of over $3 billion to this project.”

In a Washington Post op-ed in November, Buhari expressed frustration with low climate resilience investment and the constraints on developing hydrocarbon reserves, adding that “if Africa were to use all its known reserves of natural gas — the cleanest transitional fossil fuel — its share of global emissions would rise from a mere 3 per cent to 3.5 per cent.”

For Nigeria, it’s clear that utilising gas reserves is critical to energy and economic security. A few months ago, Nigeria’s Vice President Yemi Osinbajo told the U.S. Special Presidential Envoy on Climate Change, John Kerry, that Nigeria needs the exploration and use of gas as a “transition fuel”.

The Vice President also stated that exploiting gas reserves would ensure the country has the necessary energy baseload for industrialisation.

The project partners, Sterling Global Oil, New Nigeria Development Commission and Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited, seem to have found ways to raise funds for operation in an era of dwindling appetite for funding industries with high carbon emission rates.

Security trends

Nigeria’s northeastern region is currently grappling with multiple security challenges ranging from insurgency to resource conflicts and violent crime. There has been a series of violent incidents in the Alkaleri area of Southeast Bauchi.

These attacks signal the need to secure the area and address vulnerabilities, especially due to the remote nature of the sites and access from forest areas in the region. For example, a cattle breeder in Duguri District was killed and three individuals were abducted by kidnappers in August.

In July, three villages in the local government area were attacked. One person was killed, three were abducted, and three others sustained injuries.

Earlier in June, armed assailants raided five communities in the area, killing four persons while three suffered varying degrees of injury. It was similarly reported that farming activities in the Duguri, Gwana, and Pali districts had been crippled due to the risk of violent attacks and kidnapping for ransom.

The ability of security forces to address these threats could be crucial to short- and long-term oil operations. Similarly, the authorities need to ensure that land rights are protected and documented to avoid conflict while providing economic incentives for inhabitants to forestall grievances and agitations.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter