The Rise And Fall Of Settlements In Nigeria’s Ungovernable Forest Reserves

While grass huts have traditionally served as dwellings for certain ethnic groups in Nigeria’s vast forest areas, terrorists have adopted the same type of shelters due to their flexible nature, complicating military efforts.

There is not a lot to find about Dan Ganji on the internet.

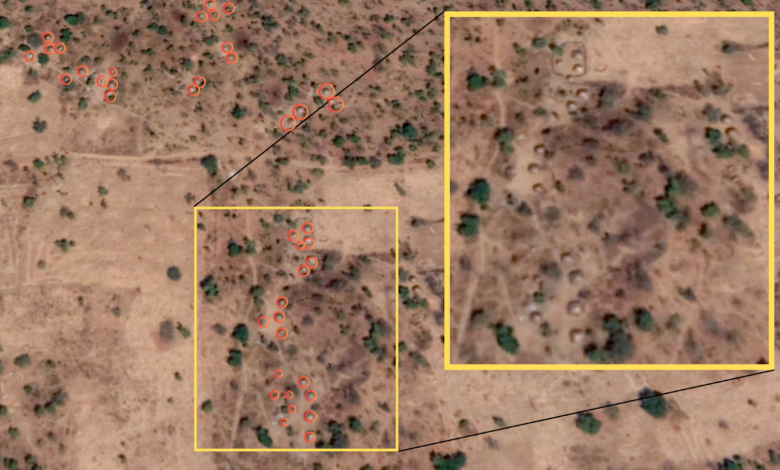

One might come across a weather forecast or a map pinpointing its coordinates and perhaps discover that it is in Zamfara, northwestern Nigeria, situated at the edge of the Kwiambana forest reserve. Locals familiar with the area suggest it’s a rural community, cut off from other areas with no major roads except for footpaths and bike routes. Experts say there used to be semi-permanent grass huts known as “Bukkaru” in the area, forming a community of typical wilderness dwellers. And that they faced persecution from terrorists and intimidation from local security groups who profiled them as terrorists, which pushed them further into the bushes. Early satellite imagery shows multiple clusters of about a hundred of these shelters.

These settlements often begin on the patches of barren land amidst savannah vegetation. From time to time, tent-like structures emerge, only to leave behind bare lands or scorch marks when abandoned or destroyed.

Large fields surrounded these Dan Ganji shelters, likely for livestock rearing and short-term crop farming. The traditional nomad settlement typically consists of a few families of herders who had settled to graze in the area.

Through extensive analysis of satellite imagery and other open-source data, HumAngle can highlight the ongoing struggle between nomadic traditional ways of life and the pressures of conflict driven by the evolution of forest shelters in Zamfara. While many of these structures serve as dwellings for certain ethnic groups, terrorists have adopted the same type of shelters due to their ease of assembly and disassembly. This complicates efforts to distinguish between peaceful nomads and criminal elements, both for state forces and apprehensive local communities, as newer shelters emerge in previously barren lands or amid the ruins of abandoned areas.

Nomadic tribes like the Fulani have a first-come, first-serve perception of land ownership. As Dr Ismail Iro – a researcher and academic spealising in Fulani history and culture – puts it in his paper: “The man who clears a parcel of land and builds his hut on it may claim rights to that piece of land if nobody else objects. When the Fulani man leaves the area, he relinquishes the claim to that land.”

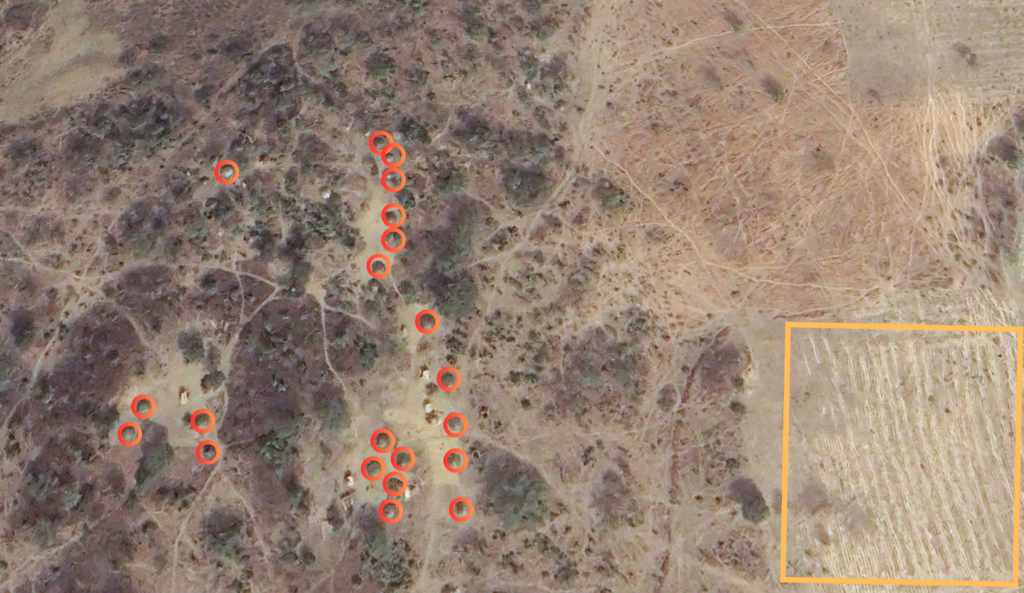

The Bukkaru is a temporary settlement mostly used by Fulani nomads. It is built by crafting millet stems, wood poles, and dried grasses into a dome. These structures are relatively easy for nomads to erect and durable enough to last as long as needed. They can just as easily dismantle them, load them onto donkeys and camels, and move them to another location.

The Dan Ganji campground, as of Jan. 31, 2024, showed plain land with no signs of the cluster that once existed. The fate of its inhabitants remains a mystery. Perhaps they moved on after a while, or they were forced away by armed herders or suspecting neighbouring communities.

Targeted by airstrikes

Similar settlements have appeared near the area recently, following the same pattern of emergence and disappearance over the years across Nigeria’s forest reserves. Most are grazing families searching for pasture as the seasons change, while some are associated with terrorism and designated by the military as hideouts or terrorist camps and subject to raids.

For the past decade, Nigerian forest reserves in the North West have been the battleground in the fight against terrorism and banditry. Footages of airstrikes on terrorists in these forests reveal that the Nigerian Air Force often targets tent-like structures similar to those in Dan Ganji.

Zamfara is arguably the centre of gravity for armed violence in the region. The state is surrounded by large forest areas on all sides, with terrorist nests in forest reserves and vast wilderness areas like Kwiambana forest and local bushes such as Fasagora, Ganda, and Gundumi. These forests extend to the boundaries of Sokoto, Katsina, and Kaduna. The extensive forest coverage is a significant factor for successful terror enterprises in these states, which face similar threats. Kebbi is another state in the North West facing security threats and, to some degree, communities around Kano’s Falgore forests.

About 30,000 terrorists are estimated to operate within these forests, utilising the vast, ungoverned landscape as bases for their operations. This terrain presents significant challenges for ground troops, making airstrikes a crucial component in the war against these terrorists.

Nigeria’s airpower has provided an edge in its fight against insurgency and terrorism. Following intensifying airstrikes on targets, the Air Force assured that troops would “stick to the rules of engagement,” using standard protocol to gather credible intelligence and identify targets before initiating strikes.

However, civilians are sometimes mistakenly targeted by state forces, who barely take responsibility. Occasionally, the military provides updates on websites and social media with pictures, videos, and coordinates of air raids, but the frequency of such updates has declined. Even when details are available, they are often riddled with inaccuracies, such as incorrect coordinates or misnamed locations.

Like Dan Ganji and many other settlements, the exact circumstances of their evolution often remain unknown. Reports have seen both local and state forces influence how these camps exist. By examining satellite imagery, we can gain insights into life in these ungoverned forests and the impact of the ongoing conflict.

No permanent settlements

HumAngle recently interviewed some victims of the 2021 Birnin Yauri abduction, who spoke about their captors, their daily routines, social life in the bushes, and the places they were held.

Various factions of terrorist groups are controlled by warlords. When a village is offered protection by the local warlord, it usually means he will keep his gang from attacking the area. Warlords are often known or recognised by their local communities. Villagers may know their farms when they are forced to cultivate them, or even their household where they go to negotiate ransom or attend to an invitation, but their hideouts are usually a closely guarded secret.

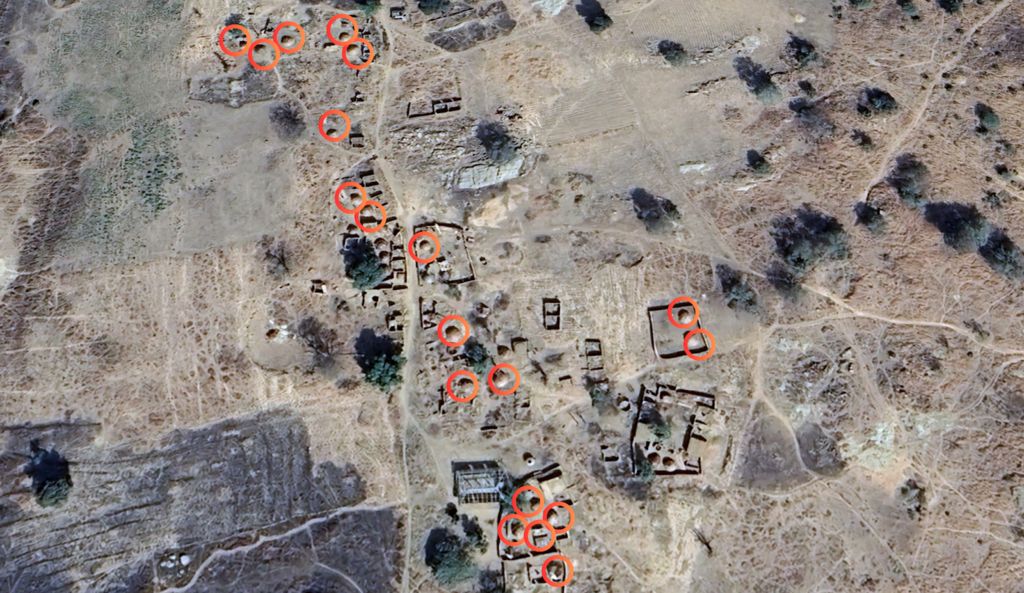

The survivors of the Birnin Yauri abduction said they were held in the forest between Dokka and Gwaska, deep in the wilderness. They were split between two campgrounds within walking distance of each other. They had compounds, living quarters and a praying area. The environment featured running water for domestic needs, a bare field where they gathered, the praying area where they congregated, and large rock hills used as sentry posts and other nuanced details. The information helped to identify areas matching this description. The camps were visible in 2018, evolved through 2021, and were likely abandoned between 2022 and 2023. Imageries available from January 2024 showed the structures completely disappeared. However, a few shelters emerged in the surrounding environment.

While we cannot be completely certain if this was the hideout based solely on witness accounts, there are numerous convincing parallels in the imagery. Additionally, many other camps have appeared and disappeared in other areas across the forest. Some lasted less than a year, most not exceeding five years before they vanished or were destroyed, while others have sprung up in recent years.

What are the signs?

One would typically become suspicious at the sudden appearance of dome-shaped structures in previously bare lands. But it would be normal if they were simply a herd of nomads grazing the area. Suspicion, however, deepens when bike routes appear after some time. If, after a long period, the vegetation near these structures remains intact and no cattle trails emerge on the ground, the natural hypothesis is that the residents are bike-riding campers not interested in domesticating livestock or settling there for long. These structures often last from a few months to a few years. Some are reappearing in areas where similar structures have been previously destroyed.

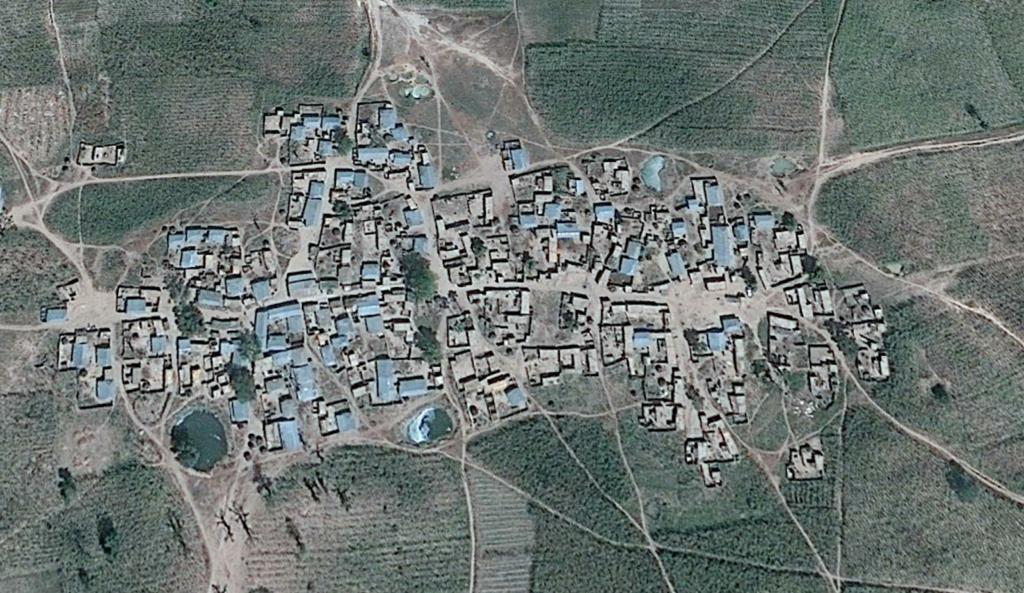

Tungar Daji is a prime example. In the last two years, more settlements have emerged amidst the wreckage of the old village. Given the current patterns, it is likely that before long, these new settlements will also be gone, continuing the cycle of rebuilding and obliteration/abandonment.

Similarly, the nameless Bukkaru settlements south of Wuya village in 2019 were a community mixed with tents and buildings. They were destroyed sometime in 2021 and reduced to building blocks by June 2022. By October 2022, about three compounds of new structures emerged. By January 2023, the settlements had expanded to include more tent structures.

These structures are like a hydra: some disappear, and more spring up elsewhere. Recent images show a proliferation of these Bukkaru-like structures in various parts of the Zamfara forest.

When a group of Bukkaru are erected together, they form a “Ruga” (human settlement). This is the most common settlement for wilderness communities. When rogues leave their families to join violent groups, they establish the same kind of living quarters they’ve known all their lives. As a result, when these settlements are targeted for destruction, there is a chance that innocent populations may be mistaken for terror hideouts. Sometimes, such raids are due to ethnic profiling.

“The settlers, especially the Fulani in these forests, are often seen as terrorists because, according to the nearby villagers, ‘it’s their brothers who carry guns to attack their villages and rustle their animals.’ So Yan Sakai [community vigilante groups] usually attack them or tell the security forces to attack them if they are looking for bandits,” said Abubakar Gummi, a security analyst based in Zamfara.

He added that, ironically, these Fulani dwellers also suffer greatly from terror attacks.

“Their armed tribesmen attack them because they believe that they are the ones giving the security forces information about them. So they usually give them two options: either leave the forest near their [the terrorists s’] territory or join them. But some of these are families with old men, women and children who only want to care for their herds. Because of that, they usually either abandon everything they own or move deeper into other parts of the bushes, away from the villages, vigilante groups, and the bandits’ territory.”

Native tribes like the Fulani, Gwari, and Kamuku still dwell within these forest reserves. They usually have a shared culture in terms of housing and isolation from places outside the bushes. This tradition is passed down through generations, preserved for posterity, and is a way of life that can not easily be changed.

Experts have repeatedly asserted that it is the responsibility of the Nigerian government to ensure that it only acts on credible intel to avoid civilian losses while doing its best to weed out those harbouring terror groups.

This report contains satellite imagery sourced from Google Earth Pro. Image analysis and illustrations were conducted by HumAngle.

Summary not available.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter