The Making and Unmaking of Abubakar Shekau

Abubakar Shekau’s fanaticism thrived like wildfire in the Sambisa Forest Reserve. His dramatic reign ended abruptly, but the scars of his terror still linger. This is how he lived.

The night air over the Sambisa forest reserve in North East Nigeria throbbed with the growl of engines. Then came the voices — distant at first, before swelling, amplified through loudspeakers mounted on the backs of trucks. “We seek only Shekau,” the fighters declared. “Surrender, and you will live.”

It was late May 2021, and two columns of fighters of the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) rolled into the dense forest in perfect coordination. Their target was not the Nigerian army, their usual adversary — it was Abubakar Shekau, the leader of rival terror group Boko Haram, who once ruled Sambisa as a self-anointed caliph while his followers wreaked havoc and terrorised northern Nigeria for more than a decade.

But this forest that once echoed gunfire and war chants now seemed overcast in ghastly silence; the fighters who had not abandoned Shekau — as many had taken ISWAP up on the chance to surrender — called it “the silence of waiting”.

In his wooded hideout, Shekau’s health deteriorated. Long afflicted with seizures, in the last days as ISWAP closed in, he reportedly suffered more frequent episodes, floating between rage and lethargy.

Within hours of ISWAP’s advance, the group’s stronghold was surrounded. Witnesses recall the confusion — frantic radio calls, bursts of gunfire, and the echo of men shouting in Kanuri and Arabic as the walls of Shekau’s empire closed in.

Then, the blast rolled through the trees.

According to an internal message released by ISWAP, Abubakar Shekau died in the hours between the 18th and 19th of May 2021. Rather than surrender, he reportedly triggered his suicide vest, killing himself and several others present. The man who had used death as a symbol of his sermons chose suicide as his final supplication.

It wasn’t the first time Shekau had died — his death had been rumoured and reported half a dozen times in the preceding years, by the military or competing insurgency groups — but it was the final, definitive time, with confirmation coming just a few days after the blast. His death ended his reign of terror, but his legacy endures across the Lake Chad region, and more broadly in the geopolitical alarm his insurgency helped ignite. It is the legacy of Shekau’s long war of mass abductions, executions, and persecution of Christians that has reverberated so far as to cause figures like Donald Trump to designate Nigeria as a land of Christian genocide requiring urgent U.S. military intervention.

Boko Haram has deliberately targeted Christians because of their faith. At the same time, the group also targets the vast majority of Muslims in the region as murtadd or murtaddūn—“apostates”—a label it applies to any Muslim who rejects its ideology, joins state institutions, or refuses to submit to its rule.

This dual campaign of violence is central to understanding the group’s impact. Many observers objected to Nigeria’s designation as a Country of Particular Concern for religious freedom violations precisely because the data show that, for every two Christians killed or enslaved, as many as eight Muslims have suffered the same fate. This underscores that Boko Haram’s violence is not only sectarian but also profoundly political and ideological, targeting all communities that fall outside its extremist worldview.

This profile retraces Shekau’s path, from an obscure perfume seller in Maiduguri to the architect of one of Africa’s deadliest insurgencies with a $7 million bounty on his head. Shekau’s caustic ideology and cruelty reshaped a region and left behind a generation born into war.

To understand why Shekau died the way he did, we must first know how he lived.

He was born in a remote village in Yobe State, northeastern Nigeria, where his early life unfolded in a modest, devout Muslim household. His father served as a local district imam and ensured that religion, discipline, and community values formed the foundation of his son’s upbringing.

Shekau was a familiar face on the village’s dusty football fields. “He was an above-average player,” one of his childhood friends recalled. “You couldn’t ignore him in a game.” Back then, everyone called him by his nickname, Babson — a name that echoed across the playgrounds from Yobe to Maiduguri in the 90s.

Shekau was a fluid midfielder, sometimes stepping into defence when the match demanded grit. “He read the game well,” said his friend. “When he played, his presence was always felt.”

Off the pitch, however, his world was more modest and solitary. For years, his livelihood revolved around a rickety Spilley bicycle and a box of small perfume bottles tied to the back. He was known as Mai Turare, the perfume seller. In one Maiduguri neighbourhood, two residents recalled his sales ritual: he’d uncap a bottle, dab a drop on the back of your wrist, and wait silently as the scent settled on your skin. Only then would he ask if you wanted to buy.

According to his mother, Falmata Abubakar, who spoke with journalist Chika Oduah for Voice of America in 2018, Shekau’s childhood was fairly uneventful. As a young boy, he left home for Maiduguri to continue his Islamic education — a common path for children known as almajirai. In this traditional system, students live under Quranic teachers, locally known as Mallamai, memorising scripture from wooden slates while often fending for themselves by begging for food.

Falmata described her son’s early years as humble and devoted to learning, but she also identified this period as the turning point in his life.

His first Islamic teacher, Malam Mande, rewarded Shekau with a bride after he memorised the Qur’an. The couple were in their late adolescence. But the joy was short-lived as his young wife died in childbirth. The circumstances surrounding the tragedy drove a wedge between Shekau and his teacher. In the midst of this great wave of personal grief, sometime in 2004, fate brought him together with Mohammed Yusuf, the radical cleric who would later found Boko Haram.

“Since Shekau met with Mohammed Yusuf, I didn’t see him again,” Falmata, Shekau’s mother, said. Her words carried both love and sorrow. “Yes, he’s my son and every mother loves her son, but we have different characters. He brought a lot of problems to many people,” she told VOA. “He just took his own character and went away. This is not the character I gave him. It’s only God who knows.”

The birth of Boko Haram

Nigeria’s transition from military rule to democracy in 1999 was rocky. For decades, the country had been governed by a fraught, violent series of military dictators who grappled for power, overthrew each other in coups, and crushed opposition with force. Corruption was rife, as was neglect of communities on the peripheries.

In Maiduguri, out on Nigeria’s northeastern fringe, the teachings of a medieval Sunni Muslim scholar and jurist, Ibn Taymiyyah, began to take hold. Ibn Taymiyyah’s ideas profoundly influenced contemporary Islamic reform movements, including Salafism and Wahhabism, by holding that the corruption of rulers justified followers’ rebellion. And in Maiduguri, Ibn Taymiyya’s writings found an audience among young people shaped by years of military rule and corruption, disconnected from a government that had long discarded them.

Among them was Mohammed Yusuf, a fiery young preacher who set up a study centre and named it ‘Ibn Taymiyyah Masjid’ in Maiduguri and hatched a group of like-minded thinkers, spurned by the government and eager for action. Boko Haram was born.

Shekau, who had been studying at the mosque, was among them and shared his compatriots’ profound rage. On occasions when he gave sermons, his voice trembled with suppressed fury as he condemned state impunity and corruption.

Muhammad Yusuf and Abubakar Shekau’s words spoke to the wounds of hundreds of youths that the state refused to see. Their promise of purity and justice, however twisted, felt like a balm. Many young men were drawn to this cult that offered dignity through resistance.

In late July 2009, clashes between the sect and Nigerian security forces erupted across four northern states. The violence, sparked by a disputed incident in Maiduguri and an initial attack in Bauchi, left hundreds dead. Rights groups later documented extrajudicial killings during the crackdown. Security forces stormed the group’s base and captured Mohammed Yusuf, who was later executed extrajudicially while in police custody. His body was riddled with bullets, behind a wall that serves as a barrier between the police headquarters and the police staff quarters. Detained in a cell at the time, I heard a senior Mobile Police officer yell, “Don’t shoot the head!” — so his body could be identified amid the heaps of corpses that were then piling up in Maiduguri. The gunfire that followed ended Yusuf’s life outside the law.

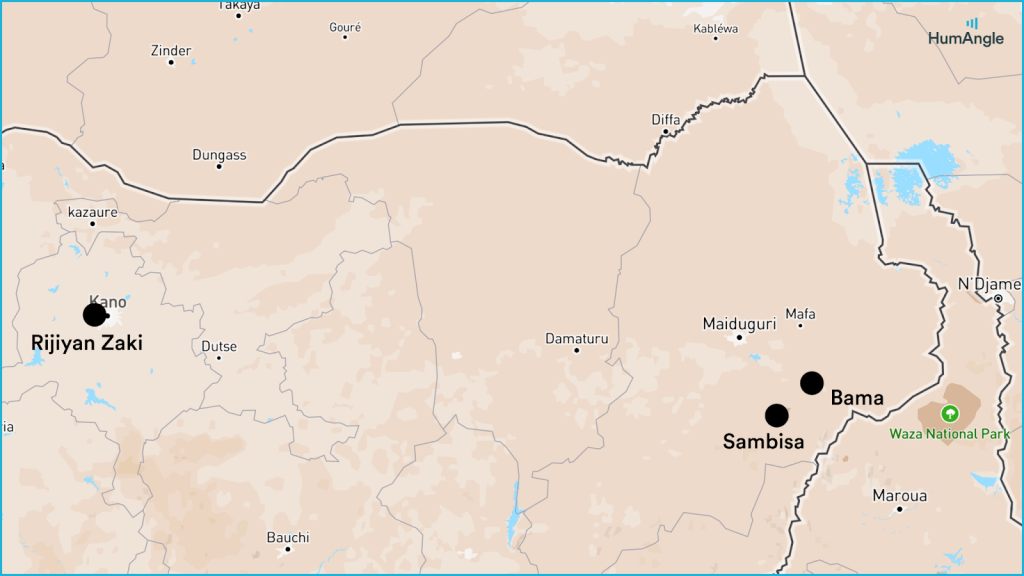

Shekau, who was wounded during a night assault on the Police Headquarters on July 27, 2009 (a bullet tore through his thigh), went underground. From the dust-choked streets of Maiduguri, he was ferried to Kano and admitted to the National Orthopaedic Hospital, Dala. Months passed as he nursed his wounds later in a rented house in the Rijiyan Zaki area within the Kano metropolis. This was when he adopted a pseudonym — Alhaji Garba — hiding his true identity from neighbours and strangers.

Shekau’s personal life was as regimented as his theology. He remarried after his first wife’s death, and later took an additional wife, Hajara, who was the younger sister of one of Mohammed Yusuf’s wives. By the time Boko Haram’s violent uprising erupted in July 2009, Shekau was married to Yana and Hajara. After Yusuf’s death, Shekau claimed one of his widows, Hajja Gana, as his third. By 2011, when he was still living in Rijiyan Zaki in Kano, he added a fourth wife, Fatima, from Potiskum in Yobe State.

“Alhaji Garba” defied the script, as bombs were being detonated at the Police headquarters, UN house, media houses and several mosques and churches in Abuja and across northern Nigeria. He cruised highways, dropped into towns, and traded pleasantries at checkpoints from the owner’s corner of his SUV and sometimes in the ’90s model of a Golf sedan.

Then came the nationwide search. Cornered in Kano, he bolted through Maiduguri to Bama, the ghost town he controlled and vanished into the Sambisa wilderness. He took with him his four wives and dozens of children

When he re-emerged, it was not merely as a man healed, but as a prophet of vengeance. Yusuf’s death and those of hundreds of sect members that were summarily executed, with their houses demolished and businesses confiscated by the Nigerian government, did not end the threat. Instead, the episode set the stage for a far deadlier insurgency under Shekau’s leadership.

Suspected members of Boko Haram were detained in sweeps across the country. Fear of arrest and persecution led many young men to shave their beards, and many women to stop wearing long hijabs. The stigma attached to families with any real or perceived link to the sect forced many to relocate; some parents did not survive the strain.

From that point, an already incensed and offended sect read their plight as state persecution. Facing the path of radicalisation, the sect found justification in fueling retribution. Their assassinations of police officers, suspected informants, and traditional rulers spread across northern Nigeria. Bank robberies, car snatching, and other crimes also became rampant in parts of the North East.

In September 2009, Boko Haram orchestrated a prison break in Bauchi, freeing more than 700 inmates, many of them adherents of the sect. The sect arrived in Bauchi with leaflets bearing their chosen name, Jamaatu Ahlissunnah liddaawati wal-Jihad (JAS), which they scattered across the city like confetti. It was the first time the sect rejected the poster name Boko Haram and proclaimed its preferred name. A sign that the group was probably preparing for a prolonged offensive showed in its manifesto dated September 7, 2009, in which it honoured its fallen members, held the state responsible for the demolition of mosques, denounced those who snitched on it and vowed to wage jihad against Nigeria. It then drew a line on the sand, threatening that “those who collaborate with unbelievers … will perish with them.” This was the seed of Shekau’s doctrine of insurgency — a war without mercy, legitimised through his bigoted interpretation of the scripture.

It would later become evident that these criminal activities were sources of funding for turning the sect into a fiery army. By 2011, Shekau’s Boko Haram moved to suicide car bombs, IEDs and coordinated raids. In Abuja, a bomber drove into the Nigerian Police Headquarters on June 16, killing several people. On Aug. 26, a suicide car bomb struck the UN compound, killing 21 and injuring dozens. In Damaturu on Nov. 4, waves of car bombs and gun battles hit police stations, churches, and banks, leaving about 100 to 150 people dead. Christmas Day attacks later that year hit churches in Madalla (near Abuja) and Damaturu, killing over 41 people. In the years that followed, suicide bombings and shootings were recorded in major mosques in Kano, Adamawa, Kaduna, Abuja, and others.

Boko Haram roughly translates to “Western education is forbidden,” reflecting the group’s rejection of Western-style schooling and governance, which they see as bearing a corrupting influence on Islamic values. Nevertheless, the group does not use the name Boko Haram. Members call themselves Jamā’at Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Da’wah wa’l-Jihād, “the People of the Sunnah for Preaching and Jihad.” This name emphasises their religious identity and mission as they see it — spreading their version of Islam through Da’wah (preaching or invitation) and Jihad (engaging in struggle) against what they consider un-Islamic authorities and communities.

The movement, and its later offshoots such as the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), have devastated the Lake Chad Basin since 2009, directly causing tens of thousands of deaths and displacing millions across Nigeria, Niger, Chad, and Cameroon — destroying livelihoods, fracturing communities, and turning once-thriving settlements into ghost towns. HumAngle has extensively documented this destruction.

A house of fear

By 2013, Shekau had become both emir and ruler in his own theocratic sovereign state. Sambisa, now a metaphor for bloody resistance, had transformed into a fortified world of trenches, checkpoints, and fear. At its core lay a settlement known as Ukuba on the fringes of Farisu, an area within the Sambisa forest reserve where Sunday Shaibu, a Nigerian Army Staff Sergeant, engaged in one of his toughest battles against Boko Haram in 2016. “When we got close to Farisu in Sambisa, the terrorists put up a fierce resistance never seen before, with scores of soldiers and terrorists killed,” Shaibu told HumAngle.

For more than seven years, Abubakar Shekau’s compound in Ukuba sat only a loudspeaker’s reach from the army’s fortified garrison in Bitta (Gwoza LGA), between 7 and twelve kilometres apart. The soldiers could hear Ukuba’s call to prayer drifting over the scrub, and the fighters heard Bitta’s in return. Yet no one crossed. A wide, invisible wall of landmines lay between them.

Ibrahim Pulka, once a courier for Shekau, ferrying drugs, food supplies, and handwritten letters or voice notes recorded and saved in memory cards to be dispatched within Sambisa and on some occasions far away, told HumAngle that the warlord’s long stay in the Farisu precinct was no coincidence. “It’s the only area in the reserve where the trees form a living wall,” he said, describing a landscape so dense that daylight often arrives dim and broken. Beneath that canopy lies a treacherous wetland, its mud deep and deceptive, swallowing even the bravest soldiers’ boots like quicksand.

Heavy vehicles and motorbikes of the counter-terrorism forces falter there; only those on foot dare to tread. And even then, death lurks beneath the soil. The area is laced with mines, so many that, according to Ibrahim, “not a week passes without monkeys being blown apart by hidden explosives.” For Shekau, who lived in Farisu throughout his stay in Sambisa, these characteristics worked in his favour, as they helped ensure that outsiders had difficulty gaining access. He introduced laws to ensure the area remained dense: no cutting down of trees, even for use in his own household. Anyone caught cutting down trees in Farisu was immediately executed, no matter who they were.

Every morning began before dawn—the muezzin’s call blended with the clatter of crockery at daybreak. Generators for the supply of electricity were ingeniously installed at a distance from the homes they powered, using underground cables, to avoid detection by surveillance aircraft that occasionally circled overhead.

Young children fetched water and shared food, which was always in abundance in Ukuba, even during times when the group faced hunger and starvation. Reaching Ukuba without an invitation was almost impossible. Its checkpoints were manned by teenage boys bearing rusty rifles. Each checkpoint was a test of a visitor’s loyalty. Inside, Shekau’s compound stood behind walls of mud and timber. Visitors surrendered their weapons a kilometre away. Those who were allowed entry spoke of a house that was neither grand nor austere. In its centre lay a prayer mat worn smooth from years of use, spread on a woven rug. A small metal box held his most guarded possessions: a handheld radio, a few documents, and a set of Qur’anic commentaries. Every decision to conduct raids, bombings, and executions emanated from this room.

Shekau’s obstinacy

In the wilderness, he built an empire of terror and servitude. One associate recalled that it was impossible to count his enslaved women; he would hand them out as gifts to loyal fighters returning from raids or after capturing villages. He fathered 26 children in total — 19 from his wives, and five from women he enslaved.

A former female captive, kept in his household for over a year as a sex slave, later recounted a harrowing experience of repeated rape and labour. “He didn’t speak much, but before sex, he would try to be chatty and touchy,” she said with teary eyes. He would force himself upon her once or twice a week, depending on his availability or her monthly cycle, back in their quarters, where other Kuyangus (sex slaves) were kept, about six at the time. The sexual abuse was so normalised that they teased her in their rare moments of laughter and jokes that she was Shekau’s favourite, considering how frequently he abused her, in comparison to the others.

She recalled that he always kept a suicide vest within reach and took personal hygiene seriously, such as frequently brushing his teeth with a Miswak (chewing stick). “I remember this because when I was passed on to two other fighters before the military rescued me, my hygiene and that of my captors were a constant source of irritation aside from the fear of death,” she recounted.

Shekau’s guards enforced his will with absolute obedience. “Those he accused of sin were forced to dig their own graves,” one former bodyguard recounted to HumAngle years later. “We would shoot them and bury them ourselves.” Another bodyguard was Ali Umar, whose obligations to his principal sometimes stemmed from reverent awe as a spiritual leader and, at other times, from fear.

On one such occasion, the hands of the man condemned to die trembled so violently that the shovel kept slipping from his grip. “He knew what awaited him. After a while, one of us grew impatient, seized the shovel, and began to dig the pit ourselves.” The man just stood there, frozen — his eyes wide, his lips moving silently as if in prayer. “When the hole was deep enough, we told him to step into it. He obeyed. Then we raised our rifles and fired. Sometimes, in those moments, we felt something — pity, grief, or perhaps shame. A few of us even wiped our eyes. But no one dared to question the orders. No one refused. To hesitate was to invite death upon yourself.”

Between 2013 and 2016, Shekau had effectively institutionalised violence as the means of governance. His command structure, once collegiate, gradually descended into a cult of personal ego. Previously trusted lieutenants either faced death or fled. In their place rose enforcers — men like Pepper, Kaka Ari, and Aliyu Ka’id — whose only qualification was their unflinching promotion of Shekau’s thirst for blood. Shekau’s rule turned the movement inward. Fighters accused of dissent vanished. Civilians, often accused of apostasy, were summarily executed.

Even senior commanders lived in dread of accusations of misinterpreted dreams or becoming targets of a rumour. One defector recounted how Shekau shot a senior member of the group, Ba Gomna, at close range, as the latter descended from his motorbike. Shekau then rode on the bike, firing into the air, celebrating the execution. The victim’s crime was that “he bought a house at Amchide, [a border town between Nigeria and Cameroon], and that was enough to kill him.”

Prominent among his victims were Bana Banki, Baba Abdulmalik, Muhammad Tasiu, Mustapha Chadi, Habu RPG, etc. Shekau himself shot some. The executions were conducted under veils of unsubstantiated allegations; the widows would be told their husbands died in battle. “This was no longer Islam,” frowned Mamman Nur, one of Shekau’s long-term associates who then defected to ISWAP mainly for this reason, before being killed by his own comrades.

Appeals to ISIS and al-Qaeda

Years before Boko Haram splintered into different factions, Shekau desperately sought relevance, validation, and alliance from global jihadist organisations. In “Appeal to al-Qaeda,” a two-page Arabic tract sent in 2009, seen by HumAngle, he invoked Qur’anic verses urging unity among Muslims. He praised Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, pledging loyalty and seeking to learn al-Qaeda’s organisational methods. He signed as Abu-Muhammad Abu-Bakr al-Shakwi al-Muslimi — a calculated identity that merged scholarship with militancy. The message expressed a desire to “operate under one banner with a clear vision to spread the true religion”.

In 2010, his voice reached beyond Nigeria when Al-Andalus, the media arm of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), rebroadcast his Eid al-Fitr sermon. It was a symbolic endorsement: the first time AQIM broadcast a message from a group outside its direct orbit. Those close to Shekau in Kano at the time said he was elated about the news. But that alliance did not last. By 2012, al-Qaeda’s affiliates distanced themselves, citing Shekau’s indiscriminate killings and theological excesses. The stage was set for new fractures.

Ansaru, officially known as Jama’atu Ansaril Muslimina Fi Biladis Sudan, emerged in 2012 as a Boko Haram splinter, vowing to “protect Muslim lives and property in Black Africa”. The group positioned itself as a moral and ideological counter to Boko Haram, accusing Abubakar Shekau of abusing power and killing fellow Muslims. The final split reportedly came after a ₦40 million bank robbery. Shekau allegedly kept the loot for himself, deepening divisions within the insurgent leadership.

In March 2012, Ansaru’s kidnapping of British engineer Chris McManus and Italian national Franco Lamolinara ended tragically during a failed rescue by Nigerian and British forces in Sokoto. The incident revealed Ansaru’s growing ties with AQIM and prompted a series of counterterrorism raids. Security forces later stormed Ansaru’s meeting points in Zaria, killing or capturing top members and dismantling its command structure. The group’s remnants retreated into the forests of southern Kaduna, marking the collapse of what once seemed a potent new faction in Nigeria’s extremist landscape.

Facing internal unease, defections, and the emergence of a faction, Shekau again sought acceptance from outside. In 2015, the group pledged allegiance to the Islamic State, an offer ISIS accepted, leading to the emergence of the so-called Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP). Yet, from the beginning, Shekau’s interpretation of the religious enterprise fell short of conforming to the objectives of ISIS. While ISIS sought territory and taxation, Shekau offered purification or annihilation.

His sermons glorified suicide bombers, including young girls strapped with explosives who targeted markets and mosques. For him, death through whatever means was proof of devotion. For people who closely followed the internal feuds and contradictions among the jihadists, it did not come as a surprise that ISWAP commanders — led by Mamman Nur and Abu Musab al-Barnawi — accused him of corruption, enslavement, and murder of Muslims. In an internal communiqué, they described his doctrine as “the Shekau deviation”. To them, he was not just misguided; he was mad.

The terrorist who loved the spotlight

Shekau was the brand ambassador of Boko Haram. Long before social media turned everyone into a broadcaster, between 2009 and 2015, he was already chasing clout with the dedication of a full-time influencer. He demanded regular video appearances and, in the process, barked orders to members of his media unit.

His men would rush to contact what he called “kafiri mai fa’ida” (useful infidel) — a reporter, in a position to ventilate his rage, often at cross with the government. Then, like an eager artist waiting for his song to hit the charts, Shekau would hunch over his radio, tuning in to different channels and every bulletin and commentary about himself.

Former associates say he was so obsessed with staying in the headlines that if the world dared to ignore him for too long, he’d summon his camera crew again. Sometimes he threatened the Nigerian government, other times he lectured the United Nations, or made appearances whenever claims of his death were made. Petty, paranoid, and painfully addicted to attention, Shekau wasn’t just a warlord; he was a man at war with silence.

According to two sources close to him, Shekau reportedly celebrated each time a new bounty was placed on his head. To him, the growing list of rewards signified his notoriety and influence. His infamy, however, extended far beyond Nigeria’s borders. Known for masterminding bombings and mass abductions, Shekau became one of the world’s most wanted terrorists, drawing international condemnation and pursuit. The United States government offered a $7 million reward for information leading to his capture or death, highlighting global concern over his violent activities. In 2012, the Nigerian government also announced a reward of more than $300,000 for his arrest. Additionally, in February 2018, the Nigerian Army separately offered a ₦3 million cash reward for information leading to his arrest.

The feared became fearful

The years that followed bled into decline. Sources close to the late Boko Haram leader said he was haunted not only by the war he started but also by a frailty he could not escape. According to them, he suffered epileptic-like seizures that often struck in waves, usually triggered by bad news — reports of his fighters being defeated or the deaths of his most trusted lieutenants.

HumAngle spoke to several associates and eyewitnesses who recalled moments when his body convulsed uncontrollably during prayers, sermons, and Shura meetings — violent episodes that seemed to mirror the turmoil within him. However, one of his childhood friends recalls that he never had seizures whenever he played football as a teenager. “It was in his 20s that I learnt about this condition he suffered,” he said, adding that Shekau’s seizure seems to be a disease whose severity grew with his age.

In the final days, as ISWAP forces closed in from different directions, he reportedly suffered up to two seizures in a single day. The attacks, according to those familiar with his condition, were likely provoked by suffocating anxiety and dread — the realisation that his end was imminent. It was this unpredictable vulnerability, they said, that made him increasingly reclusive. He avoided human contact, preferring long stretches of solitude deep in the Sambisa wilderness with those closest to him, where silence offered both camouflage and relief.

That night, when ISWAP breached Sambisa, as explosions echoed across the forest, Shekau and a few bodyguards retreated. ISWAP’s negotiators pressured on loudspeakers, promising safety if he surrendered. Inside the last line of defence, the exchange was brief, and his choice was final.

A small band of loyalists with Shekau that witnessed his final moments included one unlikely fellow, Abraham Amuta, from Benue State, North Central Nigeria, who was a graduate of Plateau State Polytechnic and deployed for his National Youth Service in Borno. He was abducted alongside Moses Oyeleke, a pastor with the Living Faith Church in Maiduguri, on April 10, 2019. Moses and Abraham were travelling to Chibok in southern Borno for Christian evangelism when Shekau’s men abducted them. The group placed a ransom on their heads. The ransom was paid. But Abraham, in a dramatic turn, reportedly turned his back on freedom, refusing to leave with his compatriot. This unusual act brought him close to Shekau, who counted him among his closest aides.

Abraham, who served in both Boko Haram’s media unit and as Shekau’s Chief Security Officer (CSO), was reported to have fought alongside him until his death.

Shekau was believed to be about 51 years old at the time of his death in 2021, according to accounts from his friends and family members.

After Shekau’s death, Sambisa did not celebrate. It heaved a sigh. The forest embraced his loss as though reclaiming what was once stolen. ISWAP moved quickly to consolidate control, absorbing or executing Shekau’s surviving men. Some defected to Lake Chad; others drifted to join armed groups in North Central and North West Nigeria. Intelligence officials referred to them as “the fragments” — fighters without doctrine, driven only by vengeance.

For Ali Umar, once Shekau’s loyal guard, the end came with both relief and emptiness. “We didn’t fear death,” he later boasted. “We feared failing him.” Shekau’s wives and concubines disappeared. Some were taken as wives by new commanders; others vanished into displacement camps. His children scattered, some adopted by the group’s members and sympathisers, others presumed dead.

The generosity of a warlord

According to members of the first generation of Boko Haram who knew him during the era of Mohammed Yusuf, beneath Shekau’s ruthless public image was a leader who never forgot his early companions. From time to time, he would inquire about those who had drifted away or fallen on hard times. When he learned that someone was struggling, he often sent financial support — sometimes through trusted couriers carrying envelopes of euros or U.S. dollars, and occasionally even small gold bars. These resources, believed to have originated from ransom payments and other illicit dealings, were part of the group’s growing underground economy.

Former members say that Shekau used this wealth not only to sustain loyalty among his followers but also to lure back those who had left. His generosity was both a gesture of kinship and a calculated strategy for consolidating influence. One of the most notable examples was Mamman Nur, a senior figure who had abandoned the group before the July 2009 uprising and relocated to Cameroon.

There, Nur lived modestly, eking out a living as a commercial motorcycle rider and struggling to feed his family. Word of his condition reached Shekau, who soon invited him to return. Along with the promise of reconciliation came the offer of power and resources. When Nur rejoined, Shekau appointed him to a senior leadership position, granting him access to funds and logistical networks that helped shape Boko Haram’s operations in its early years.

The echo of one man’s madness

Shekau was a product of a system that fused ignorance, state brutality, and the politicisation of religion. When Mohammed Yusuf’s movement was fractured in 2009, it was not ideology that survived; it was anger. The state’s failure to provide justice became Shekau’s first platform of relevance. Each time a civilian was summarily executed after military raids in homes and public places, each time a mosque was demolished or a detainee tortured, the anger received further oxygen, and the insurgency gained recruits.

Yet Shekau’s doctrine went beyond politics. His idea of divine purity justified murder as worship. Even his followers were never safe from this obnoxious logic. Those who left were labelled apostates; those who stayed became executioners. He ruled through strange doctrines and terror, but both were built on the same principle: that human life could be weighed against one man’s interpretation of faith.

For the Nigerian state, Abubakar Shekau’s death marked the end of a man, but not the end of what he set in motion. His body was torn apart, but his fury, his words, his defiance reverberated across the Sahel. ISWAP endures — leaner, more calculating, and far more disciplined — while new factions emerge across the Sahel, carrying shards of his chaos and shaping them into new weapons and machineries of war.

The poisonous doctrines Shekau preached remain disturbingly resonant across northern Nigeria and the Sahel. It is not his violence that draws sympathy, but the sense of grievance and moral rebellion that underpinned it. For the few who embraced his violent creed, perhaps one in a hundred, their numbers still run into thousands, enough to reshape the fate of entire regions. They kill Christians when they can, and they kill Muslims who refuse to bow to their fancied divine authority.

In parts of Borno, Yobe, and northern Cameroon, Shekau’s message once spread like harmattan fire. Whole communities, long betrayed by state authorities, wallowing in poverty, and repressed by official corruption and neglect, recognise in his sermons a voice of rage, resistance, and a dream of revenge.

Men like Shekau did not rise in a vacuum; they drank from the wells of radical clerics who preached hate and intolerance unchecked by the Nigerian state. Under this caustic ideology, Christians were hunted and Muslims who dissented were condemned; no official or aid worker was spared, all profiled as agents of “Taghut”. Now, many who still fight beneath Shekau’s banner were born into it — children who never knew peace, who learned to recite the Qur’an to the staccato of gunfire, who bowed at dawn and raided by dusk. His legacy is not the scripture he claimed, but the scars carried by children born into a storm they did not start and cannot yet escape.

This report draws on archived materials and interviews with over ten individuals — among them former associates, friends, bodyguards, and captives of Abubakar Shekau — whose testimonies provided critical insight into his personal life, network, and operations.

In May 2021, the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) targeted Abubakar Shekau, the leader of Boko Haram, in Nigeria's Sambisa forest.

Faced with surrender, Shekau committed suicide, ending his reign of terror characterized by mass abductions and executions across northern Nigeria and the Lake Chad region.

From humble beginnings, Shekau rose to infamous leader, heavily influenced by Mohammed Yusuf and radical Islamic teachings.

His leadership saw Boko Haram engage in severe violence, including bombings and kidnappings, drawing global condemnation. Despite his death, Shekau's legacy endures in ongoing regional instability and the ideologies he propagated continue to influence insurgent groups in Nigeria and beyond.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter

Weldone for this in-depth and mind blowing analysis of the life of one of the most dreaded and feared terrorist in the whole of the Sahel. My question will always remain. Where did he get his funding after been dislodged by the Military in 2009? It was mentioned here that he letter got funding from kidnapping for ransom and Armed robbery attack. Where does the initial funds came from that was used to acquire arms,thereby using it for their I’ll vices. Is it true that he was been sponsored by politicians? Because from all your analysis,I doubt if any politician can even approach him for such offers. Kindly shed more light on the areas of Funding. Thank you

“Ibn Taymiyyah’s ideas profoundly influenced contemporary Islamic reform movements, including Salafism and Wahhabism, by holding that the corruption of rulers justified followers’ rebellion.”

I would like to see the evidence supporting this statement. As far as I know, this is almost direct opposite what Ibn Taymiyyah preached.

I would like to see your supporting evidence. Thank you