The Journey Of Boko Haram Defectors Through Geospatial Lens

Thousands of defectors consisting of combatants and non-combatants navigate through water bodies and thick vegetation while at the same time evading interception from hostile insurgents during their rough journey to the other side.

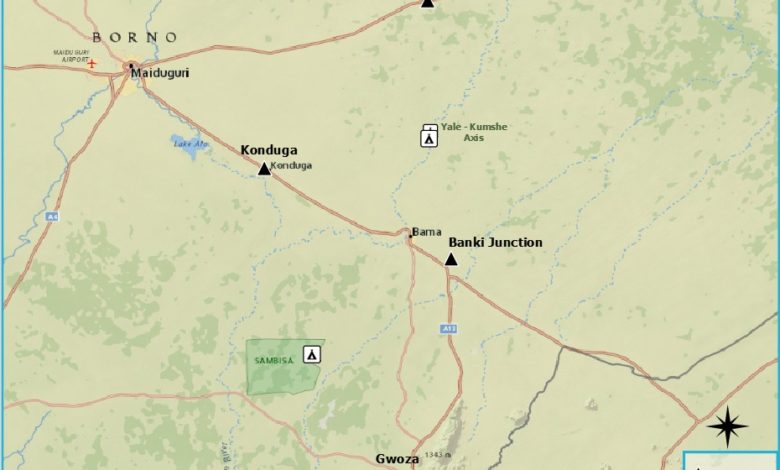

Once a vast shrubland known for its distinct biodiversity, Sambisa forest has become synonymous with Boko Haram and the centre of gravity of the recent wave of mass terrorist defection.

Located in the southwestern part of Chad Basin National Park and close to the Mandara mountain range in Northeast Nigeria, the forest and the adjoining environment provide sanctuary for insurgents from military campaigns as well as resources for their survival and operations.

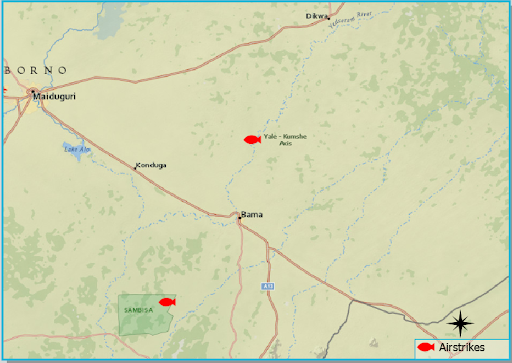

The Nigerian military has published several multimedia materials on ground operations and bombing runs targeting fighters and settlements in Sambisa, often with buildings hidden amid trees.

Over the past few weeks, thousands of persons associated with Boko Haram consisting of fighters and civilians have fled the Sambisa general area and flooded nearby garrison towns, navigating through the challenging terrain of muddy grounds and thicker grasses and shrubs that accompanies the wet season in the region.

The mass defections towards Konduga, Bama, Gwoza, and Mafa Local Government Areas (LGAs) are part of the aftershocks of the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) assault on the group’s stronghold, the subsequent death of Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau, and attempts to absorb the group.

The mass defections have been influenced by numerous factors, one of them is the ideological differences between the two groups. For instance, Shekau’s takfir creed, which means Boko Haram considered everyone outside its territory an “infidel” to be killed, including other Muslims.

While ISWAP does not believe in this, and although more deadly and tactical, it has a category of people designated as targets such as humanitarian actors, security forces and vigilante members.

For some of those defecting, it is because they can’t live under ISWAP’s creed or authority that they are leaving. Some of the other people defecting, however, include conscripts, captives, and civilians.

Sensing a window of opportunity amid the ensuing chaos and changes, more than 5,000 combatants and non-combatants surrendered to state officials and began their journey through a complex process involving profiling alongside designation for release, prosecution, or rehabilitation.

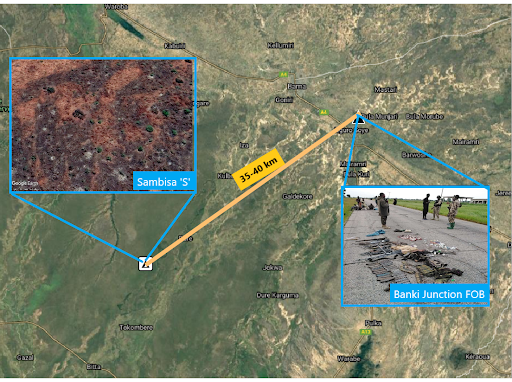

Hours-long journey from Sambisa to Banki-Bama

The journey to defection is between 35km and 40km from the Sambisa axis to Banki, a town in Bama LGA near the border with Cameroon. Defectors arriving at Banki were received and processed by the military at the outer perimeter of the town recaptured by troops from Boko Haram in 2015.

As of Jan. 2020, there were reportedly 42,055 displaced persons in Banki camp from areas such as Kangaleri, Charianari, Bama, Konduga, Kumshe, Nduguno, Dipchari, Jere, and Minwawo.

Potential movement of insurgents through this corridor would involve coming across environmental elements consisting of low tree canopies and thorny plants through relatively flat terrains, as they moved further away from the undulating configuration of the Sambisa forest area.

They would also come across little patches of water bodies and, depending on their trajectory, cross the tributary of the Yedseram river at least twice. The overall geography of this travel path is somewhat similar to the environment they interact with daily at the heart of the Sambisa forest.

Their path encompasses vegetation made of short plants as well as an open surface rock-type terrain similar to those found on the path leading to the mountainous area.

If defectors had the foresight or felt safe enough to push ahead, they could move through the other route with apparent human activities, as the journey would pass through pockets of settlements and the adjacent side of the Bama High School, crossing the Zungeru-Kure road and a sparse collection of mosques.

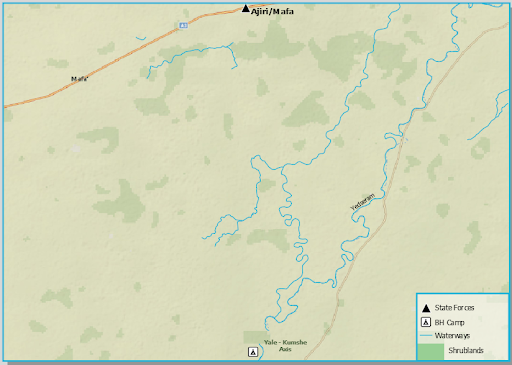

Rainy season complicates northward trip to Mafa

Boko Haram insurgents, particularly those within the Kumshe axis, have the option of choosing between defecting to the Nigerian Military in Mafa-Ajiri or South towards the Banki junction in Bama.

In the dry season, the trip to Mafa would involve travelling 25km through dry surfaces ladened with vestiges of shrublands and water channels that become recharged during the wet seasons. Defectors approaching the Forward Operating Base (FOB) in the Ajiri area of Mafa will initiate their route in the surrounding areas near the fringes of the Yardesam river.

The defectors may not have to cross, depending on what section of the river they start from. However, up ahead they would face the challenge of crossing through the 216m path across marshland that is about 1km wide.

The alternative to this path is to make a short trip around, which would add between 12 to 15 extra minutes to their walking distance as they manoeuvre.

Moving on, they would encounter greener and thicker vegetation along the path with little patches of bare surfaces. Also on this path, the size and assemblage of water bodies increase as one progresses.

At about 11km through, they are expected to come across at least one of the tributaries of the Yardesam river, after which they would run into more marshlands.

A significantly waterlogged terrain is situated about 9km from the last one at the inception of the trip. They would have to navigate this 7km area with tributaries stretching in both the right and left directions, which are sufficient to dissuade travellers from attempting to go around.

An attempt to circumvent the water body would increase the hours ahead for the defectors who are also threatened by insects and, worse, an interception by rival insurgents. The remaining 15km distance to the Mafa exterior and trench would involve forging northwards through wetlands of similar nature, with few options for evading this terrain.

Those who turned up in Konduga

The options for defectors who turned up in Konduga are either to travel about 42km from the edge of the Sambisa forest to the town or travel about 35km from an enclave such as Bone to Konduga area.

The journey from the Sambisa axis involves going through the Sahelian savanna-type vegetation of sparse trees and short grasses along a vast open land area of flat terrain. They might only need to cross a stream of the Yardesem river once.

The journey from the Bone hideout or area around it is similar to that of persons in the hinterland of Sambisa heading to Konduga. The defectors would, however, have to go through about 8km of densely vegetated surfaces before entering the zone of dry land and open ground rock surfaces.

Apart from the challenging environment and obstacles, defectors surrendering to Nigerian authorities also avoid hostile insurgents in the course of their journey.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter