The Illusory Truth Effect And Why Army’s ‘Fake News’ Tags Are Tricky

The Nigerian Army, the security agency responsible for land warfare, has recently stepped up its war against “fake news” but its controversial approach comes at a cost for its integrity and the trust the public may have in the media.

An analysis of over 5,400 tweets on the verified handle of the Nigerian Army posted since April 2013 shows that it has mentioned the words “fake news/publication” at least 67 times. In 56 of those tweets, mostly from 2020, the security agency was calling out various media publications or other reports.

The first time such a tweet was made was in September 2017, in reaction to a publication by PM News Nigeria but it has since been deleted. In the second instance the following month, the Army reacted to a report by Vanguard Newspaper which said people panicked in Port Harcourt, Rivers State, over forced vaccination against monkeypox by soldiers.

After these two tweets, the following related posts were more detailed, sometimes involving the use of press statements to rebut misinformation. For example, in the series of tweets from September 2019, the Army took time to explain why rumours about planned terrorist attacks should be disregarded.

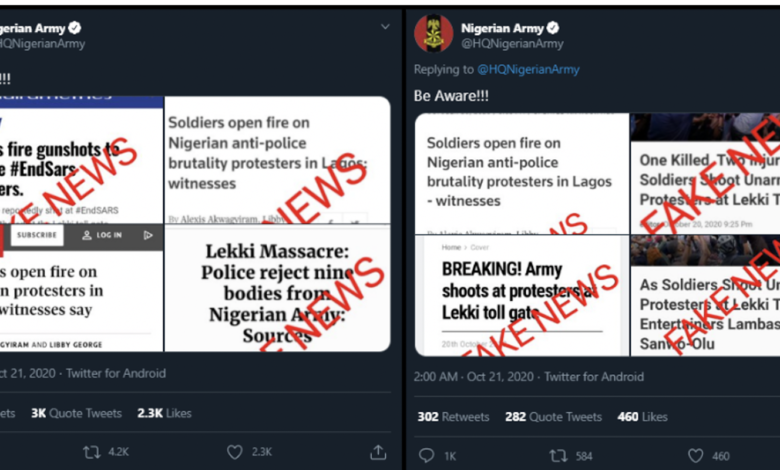

However, starting from July 11, 2020, a change in approach was noticed. On this day, the Army uploaded screenshots of publications by Global Sentinel and Premium Times about the voluntary retirement of 256 soldiers and stamped them, in bold red fonts, as “FAKE NEWS”. It again added captions, but in the screenshots this time, arguing that the disengagement was a normal routine and that the force was not in short supply of willing recruits.

In most of the 32 “fake news alerts” shared since then (between August and November), no further explanations were provided. The notices only had screenshots from the online reports, an eye-catching “fake news” stamp, and a caption that said either “fake news” or “be aware,” often accompanied by three exclamation marks.

Unlike conventional fact-checking, this approach makes it difficult for people to understand why a news report should be considered untrue.

The inclination to describe unfavourable reports as fake is not limited to the Nigerian Army. In November, for example, Nigeria’s Information Minister, Lai Mohammed, dismissed a CNN investigation about the extrajudicial killing of protesters in Lekki as “fake news” and “misinformation,” without specifically explaining why.

Introducing the illusory truth effect

For a lot of people, what is true hardly matters as much as what is viral or repeated often. This is a cognitive bias known as the illusory truth effectㅡor, alternatively, the validity or reiteration effect. For instance, the government may, for instance, succeed in convincing people the economy is faring well despite evidence to the contrary, simply because it keeps repeating the deceitful claim.

Repeating a claim makes it appear more believable and, according to experts, the best way to avoid becoming a victim of this bias is to be on the lookout for such statements and then actively consider “what objective facts corroborate each version of the events.”

United States President Donald Trump is one person who seems to have prominently taken advantage of the illusory truth effect. He has, in fact, been credited with popularizing the phrase, “fake news.” During his campaign and since his election in 2016, Trump used the phrase loosely and frequently to describe news about himself which he considered unsavoury.

“You know why I do it? I do it to discredit you all and demean you all so that when you write negative stories about me no one will believe you,” he said in 2018. And it has worked, with the number of people having confidence in the press plummeting hard over the years.

The regard the Nigerian Army has for Trump’s approach to the press likely dates back years. Notably, in November 2018, it referenced, in a now-deleted tweet, a video of the U.S. president to justify opening fire on protesting members of the Islamic Movement of Nigeria (IMN).

“When they throw rocks… consider it as a rifle… They want to throw rocks at our military, [then] our military fights back,” Trump had said in the clip.

Meanwhile, the wanton use of the expression “fake news” is questionable, considering how it has become weaponised over the years. Experts have observed three common uses of the term: to describe misinformation, to discredit disliked claims, and to undermine or delegitimise the source of a claim, especially news platforms, even if the claim were true.

“The dismissive usages of the term ‘fake news’ are particularly problematic because they do not leave room for critically evaluating a source or its message, which can lead to gaps in understanding of consequential information,” says Tamar Rubin, an information literacy expert.

“If the term, ‘fake news’, is being used to describe everything from intentionally fabricated fictional news stories to legitimate news sources that are simply reporting on a controversial topic, then the term cannot be considered a reliable indicator of whether a source is trustworthy.”

Rubin instead recommends the use of more specific terms such as “misinformation” and “disinformation”.

Fact-checking truth with falsehood

Although fighting false information, especially through broadcast and online media, has recently been one of the Nigerian Army’s key interests, the agency itself has several times had its hands caught in the cookie jar of misinformation.

Back in July, the army was quick to label a Premium Times report about hundreds of soldiers retiring due to a loss of interest as “fake news.” But documents later surfaced confirming the report to be true.

Months earlier, the army had similarly debunked another report on the suspension of approvals for voluntary retirement applications. But the newspaper then published a copy of the internal memorandum, substantiating its story.

More instances came to light during the EndSARS campaign in October. In one of such, the army first described a hooded official who called on his colleagues not to kill demonstrators in a widely circulated video as a “fake soldier.” Two days later, it announced that it had identified and arrested the official for cyber crimes.

Similarly, the army went from claiming none of its men was at the Lekki tollgate and that no shots were fired to explaining that it intervened after it was invited by the state government and that its men only fired blank shots.

It is quite surprising that, despite the obvious conflicts in some of its statements, the Nigerian Army has hardly deleted any of the concerned tweets. This reinforces the theory that it may have a goal bigger than just “fighting fake news” and may be banking on the illusory truth effect to promote distrust in the mainstream media.

The cognitive bias is so effective, says Psychology and Cognitive Science expert Tom Stafford, because the instinct of the average person is to use “short-cuts in judging how plausible something is.” Though helpful, this can be misleading. The first step to guarding against the bias is to learn about it, Stafford suggests.

He explains: “Part of this is double-checking why we believe what we do – if something sounds plausible is it because it really is true, or have we just been told that repeatedly? This is why scholars are so mad about providing references ㅡ so we can track the origin on any claim, rather than having to take it on faith.”

Importantly, the army’s casual method of fact-checking may not just worsen distrust for media publications but can also harm its reputation.

“Credibility is the cornerstone of effective narratives,” argues Dr Abdullahi Tasiu Abubakar, a journalism lecturer at the City University of London, in reference to the army’s communication strategies. “Honesty – or the perception of it – is a necessary condition for the long-term efficacy of strategic communications.”

The current government has repeatedly listed winning the fight against insurgency and other forms of insecurity as a top priority. But to achieve this, media practitioners have insisted, it needs to see journalists and other opinion-shapers as partners in progress and not enemies who must be crushed. Security agencies, especially the Nigerian Army, must also be committed to sincerity and transparency, so long as this does not compromise the security of the country.

The researcher produced this article per the Dubawa 2020 Fellowship partnership with HumAngle to facilitate the ethos of “truth” in journalism and enhance media literacy in the country.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter