The Ghost Town Of Bagana

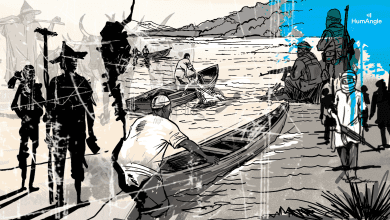

How two warring chiefs turned a commercial hub upside down, displacing thousands of its residents in north-central Nigeria.

Bagana, a once thriving market town in Kogi State, north central Nigeria, is a ghostly shell of what it once was.

Two warring clans have been fighting over the market, the town’s best asset. The violence has killed scores and chased many away. The people forced from their homes are now counting the cost.

Michael Audu* was born in Bagana, the community in the Omala area of north-central Nigeria. The son of a rice farmer, Audu is a graphic designer who now lives in Abuja, nearly 50 kilometres away.

He remembers an idyllic place, a world filled with traders, trees, and birds. All that is now gone.

He relocated to Abuja in April 2022, when the conflict between the Emagede and Patanyi clans was at its height. But eight months after moving, Audu still has nightmares. The horror was too great, too overwhelming, he said, “I saw a well-organised community disintegrate into something unrecognisable.”

For someone who had never seen dead bodies lying on the street, Audu saw too many in 2022 and it broke something inside him. He could not explain what it was exactly, but he admitted that he had changed a great deal.

Whatever broke inside Audu had kept him awake at night and engaged his thoughts by day.

Audu’s father was killed in an attack on his farm, Audu believes the attack was connected to the crisis.

“My pastor told me to fast and pray for 30 days in June last year and later I was asked to always fast in the first week of every month, but this insomnia has persisted. It is as if it is hard to feel normal again. You know I held my father until he breathed his last. That was June 14, 2021. This thing does not leave you as early as you would want it to.”

On May 23, last year, Audu was far away in the safety blanket of Abuja when he got a call from home that his mother had also been killed in one of the tit-for-tat attacks between the clans.

Now an orphan at 26 and displaced, he can hardly focus on the things he used to be passionate about. He might be walking on the street and a shrill sound of a car in the bustling town of Nyanya would take him back to his birthplace. His customers have started to complain that the quality of his work has declined.

“Whenever I send a new work now, it is often being sent back to me for more edits,” he explained. “I used to really enjoy designing flyers, banners, and ID Cards but now they don’t interest me that much. I wish you knew what I was before I became like this.”

Strangely, even when Audu talks about his troubling experience, he is all smiles. But the smiles mask torment.

He painted another striking scenario about his current state of mind. Sometimes, when he walks down the street, a burst of loud laughter from the sidewalk tears at his heart.

In his mind, this harmless laughter feels like mockery, like all the things he had lost. The reason might be that back in Bagana, he sometimes heard loud laughter at night coming from the bush.

Dorcas Francis*, his girlfriend, believes he masks his trauma with laughter: “I try to overlook some things he does because of the things he told me he had gone through in the past but sometimes his nagging gets to me,” she said, adding that he gets angry and confrontational easily.

The most striking thing about Audu is that he is connected to both warring clans. His father was from the royal family of Emagede and his mother was born to a Patanyi farmer.

The dispute between Emagede and Patanyi is over who should control a major commercial hub called Bagana Market. Both parties want sole ownership and are not willing to share.

The market racks up a weekly revenue for its controller of about ₦500,000 to ₦800,000, according to a source within the military assigned to gather information on the crisis. Because of its strategic location and profitability, the controversy over who should control it began to stir up more aggressively. It reached a crescendo in Aug. 2o21 when both parties who claimed ownership took up arms to fight each other.

Now a shadow of itself, Bagana was once a densely populated town with thick forests, steep-sided mountains, scraggly-red pebbles that were coated with light sand, and a warm community of mostly farmers who welcomed people from far and wide on market day. The community is close to four states: Benue, Edo, Enugu, and Nasarawa. Every five days, people from these neighbouring states troop in to buy and sell.

It is mostly inhabited by the Patanyi, Emagede, Hausa, and Nupe.

How the crisis erupted

The smooth-running wheel of the market had already been knocked off-kilter when the news came that Solomon Obochi, the High Chief of Patanyi, had been kidnapped.

Suddenly everything became much worse.

“From Aug. 28, 2021, when he was kidnapped, life has not been the same,” Sarah Uja, a 28-year-old tailor who fled the town, said.

The disruptive conflict escalated after that period. Violence suddenly became the norm in the town.

“The intensity was visible at the start of August. Residents were already preparing for the worst, but when the chief was kidnapped, we knew we were close to seeing hell,” Akoja John, a farmer, said.

John could no longer walk properly. He had a near-death experience on his farm, where he was beaten to a pulp and left to die. The incident has broken him and deteriorated his health, he said.

Once a man with a house and a large farm, he is now forced to live in exile at Abejukolo in another part of Omala — with painful memories of his burnt house and a farm he no longer believes existed.

“Life has dealt more blows than we can handle in the past year. This conflict has taken a lot from us. It took some of our families and made us homeless. It took away our peaceful community,” John, 34, spoke of the violence with a sharp look that suggested he had never seen something quite as terrifying.

The chief’s death and the carnage

Following Chief Obochi’s abduction, the town became uninhabitable, especially with the captors refusing to release him until a huge ransom was paid.

Residents already saw signs of war. Fingers were pointed at Obochi’s Emagede rival, suspected to have had something to do with the abduction.

“The town’s market was recording its lowest turnout. The way things were going at the time, you just knew it wouldn’t take long before something bad happened. Shortly after, what everyone dreaded happened,” recalled a resident who asked not to be named.

After a few days, people learnt, even though the demanded ransom of ₦3.4 million ($7,400) had been paid, Obochi had been killed. His body was found on a road leading to the market.

It felt like the world was coming to an end, Gabriel Johannah said. Panic grabbed the town by its scruff. Everyone was talking about the brutal manner the chief was killed.

Johannah saw the chief’s dismembered body. Blood stained the worn-out road and the expression on the corpse’s face told stories of excruciating pain. “It was a gruesome death. One that triggered the entire community of Patanyi people,” he said.

Before 4 p.m. that same day, many more dead bodies littered the street. Houses were brought down to rubble, including that of Salifu Anyebe (also known as Onu Otutubatu), the high chief of Emagede.

Within the four walls of many homes, hearts beat with fear. Johannah explained that no one had come this close to death or ever had any reason to be fearful for their lives. “This has never happened before. So, when it did, it opened the large town to one of the worst inter-tribal conflicts with casualties on a large scale.”

“A conflict that has fallen many heads and driven thousands from their home cannot be for nothing. It is about ownership and control,” Johannah said.

The war has a prize; a prize so valuable the two conflicting clans were moved to spill each other’s blood for it.

“This is not a pointless conflict between Emagede and Patanyi, but is it worth the lives and property that have been lost? I don’t think so. People took each other’s lives like they had never eaten on the same plate or gathered under a tree to discuss football,” said Blessing Oche*, a farmer from the Ihiankpe community.

According to a security source in Omala, since the death of Chief Solomon Obochi in Aug. 2021, over 100 lives have been lost and so many properties destroyed. Also, not less than 10,000 residents have fled Bagana to find refuge in neighbouring towns such as Abejukolo and Idrissu.

Peacebuilding efforts

Not less than three committees have been set up in the past to bring the conflict to its end. Amongst the solutions they recommended was that the two chiefs, one of them now late, should go back to their original domain a few miles away from Bagana.

The committees established that neither of them could lay claim to the community.

This recommendation was first proposed by the seven-man committee set up in 2007 by former Kogi governor Idris Ibrahim, who also hailed from the local government area. The committee argued that the only antidote to the crisis was the chiefs vacating Bagana. Two other committees – set up in 2008 by the late Attah Igala and in 2022 by Omala local government chairman Yakubu Aboh – also made a similar proposal.

Chief Salifu Anyebe of the Emagede resisted these demands.

“Recently, a chief from Abejukolo together with the Commissioner for Local Government and Chieftaincy Affairs in Kogi State summoned me to a meeting on June 10, 2021, in the ministry, only to threaten me to move out of my palace in Bagana,” he said.

“They explained that it was my presence in Bagana that usually generates tension in the area. I felt that this directive was biased and lopsided to a great extent, because they never wanted to know who actually owned the land in Bagana and to identify who was fomenting trouble, so as to know and take the necessary action. Rather, they were only interested in threatening me to relocate and forfeit the heart of my domain to them.”

The chief said previous court cases ended in his favour, so he had no reason to leave.

Yakubu Aboh, the Chairman of Omala LGA said his administration had done all it could to restore peace, saying the loss of lives was saddening and could never be justified.

“We are saddened as a government and as a people. We condemn this act in its entirety. No stand to justify a man taking another man’s life. We commiserate with families of those who lost their lives in this incident,” he said. He mentioned that the market has reopened and peace is gradually returning.

Audu, who belongs to the Omala Sons and Daughters in Abuja, said women must be involved in resolution committees to build long-lasting peace.

“You know in all the peace committees you have mentioned, none of them has women and they are the people that are mostly affected by the conflict. I believe for lasting peace to return, we also need to bring women to the table to hear their views and solutions,” he suggested.

Like in Bagana, women are often excluded from peacebuilding efforts across the world. According to United Nations, women served as only six per cent of mediators, six per cent of signatories, and 13 per cent of negotiators globally from 1992 to 2019.

Faith Ajeka, a spokesperson for the Omala Sons and Daughters group told HumAngle they have written to several stakeholders, urging them to act while also visiting government officials and traditional leaders.

“We will continue to do more and we want Bagana to go back to how it used to be. It used to be a welcoming and peaceful community,” she said.

The local government chairman announced in Sept. 2022 that it was now safe for residents to return but, Audu said, many people have advised him to wait and watch how long the peace would last before taking this step.

“I am not sure I would be able to stay there again but I would like to go home once in a while to have a feel of the place when peace has been totally restored,” he said.

Most of the people who spoke to HumAngle confirmed that Bagana is safe only on market days when security is beefed up from dawn to dusk. Otherwise, people have been able to summon the courage to live there since the conflict.

A retired officer in exile

Yunus Halilu*, a retired police officer, has stayed in Abejukolo and hasn’t been able to return to Bagana since the crisis worsened. According to him, many farmers have been murdered on their way to the farm and more people fled last August when the violence became worse.

“I left Bagana on the 28 of August and by evening, I heard it had turned into a bloodbath. Within three months, I lost my son and stepbrother, who were attacked on the farm and murdered,” the 65-year-old said.

“My stepbrother’s farm was close to mine. They went briefly that morning to check their trap and that was how they met their deaths.”

He also lost another close relative in April and has been shaken by her death.

“We grew up together and went to the same primary school. So, I have seen her as my closest relative for a long time which made it hard for me to move past her death and that of my son.”

Halilu’s four-bedroom flat in Bagana was burnt down too.

“Everything inside was carted away. And this is everything I have laboured for as a police officer all my life. My three shop buildings on state road were also burnt down with their contents looted,” he said fighting tears.

His two-bedroom guest house was reduced to rubble and his farm was destroyed as well.

A few minutes after Akor Boniface, 41, received a call from a security officer about a possible attack in Bagana that evening, he began to hear gunshots.

“I remember that it was Aug. 29 around 10 p.m. So many people were shot dead that night and I saw corpses being deposited at the Bagana river. Luckily for me, I got a call from a security agent about the attack and he gave me tips on how to escape.”

Boniface escaped to Abejukolo barefooted after hiding in the bush for two days without food.

“I saw men with guns walking around. I could not recognise the faces. I was lucky that I was not caught,” he narrated. His house was among those burnt down. The cement blocks they moulded for an ongoing construction of his brother’s house were also destroyed and trees were cut down.

“No one has been able to sleep in Bagana for the past two years. It is a ghost town with burnt houses. I have lost my farm, my house and my loved ones, you see I almost lost my life too.”

He still has nightmares from seeing how his brother’s son was slaughtered on his way from the farm.

*Names of sources have been changed to protect their identities.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter