The Exploitative Slot Systems Targeting Desperate Job Seekers in Nigeria

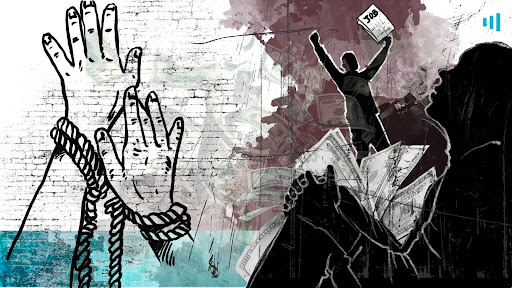

As many Nigerians battle unemployment amidst the cost-of-living crisis, inadequate opportunities, and economic inequalities, others profit from this system by selling ‘job slots’ to desperate job seekers. Many of these never materialise, leaving them to battle economic loss, among other risks.

After Zahra Usman* quit a job she described as toxic in a law firm that overworked and underpaid her, affecting her mental health, she found herself searching for a job for over a year. She applied for every opportunity she was qualified for, and that was how she came across one that promised a role at the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) in the United Nations in 2024.

“My friend sent the flyer to me. It looked like a legit job application. The job had different roles, including legal assistants, and that was the role I applied for,” she says, recalling having no doubts at first, as she submitted her cover letter and curriculum vitae (CV) to the provided email address.

She did not receive an acknowledgement email and eventually forgot about it, as it was common not to hear back after applying for a job. However, in April 2024, they sent an email claiming they were recruiting again. Since she had already applied for the other role, they said they reached out because she met the requirements for the current position.

“They asked me to confirm my interest, reply to the email before the deadline, and send in an updated CV,” she recalled. They even offered an estimated salary of $2,ooo and links to calculate the tax requirements. They also said that due to the high level of applications, they couldn’t reply to individual queries.

After sending the CV, she didn’t hear back from them until May, when they informed her that she had gotten the job. They asked her to return the signed appointment letter, do a BSAFE assessment (a mandatory online security awareness training for all UN personnel), and submit the certificate. It took her almost the whole day to process the certificate, which required taking short courses and tests for each segment. The final test required answering 80 per cent of the questions correctly. Even though the process was stressful, Zahra still ensured she did it on time.

They also requested a Quantifiable Emotional Intelligence, Racial and National Diversity, Inclusion, and Validation Certificate (QREDIV). Still, when she followed the link, she discovered a payment of $99, which was about ₦160,000 at the time. At first, she wanted to borrow the money from a friend, but she became suspicious.

Employment scams were ranked as the second most serious type globally in 2023. Scammers exploit the economic crisis and high unemployment rates by promising lucrative opportunities with reputable companies. This includes fake job postings, phishing emails, and fraudulent job advertisements, many of which go unreported in the country. There is a lack of proper structures in place to trace and address these cases, and feelings of shame often prevent victims from speaking out. Additionally, some of these scams involve fake interviews designed to lure victims into situations where they could be kidnapped for ransom demands from their families.

“I entered the third-party website, and the whole thing made me suspicious. That was why I started to conduct proper research, to be sure, as it felt weird that the UN was expecting me to pay for any course. I searched for James Hall, who signed off all the emails on LinkedIn, but I couldn’t find him, and that was when I started to get more suspicious,” Zahra said.

The 29-year-old trusted her gut and decided to dig even deeper. She searched on Google to find out if the UN requires payment for courses, which led her to the Naija forum, an online platform where Nigerians shared their experiences. The search also led her to a disclaimer by the UN that they don’t charge a fee at any stage of the application process.

“Everything seemed so genuine. I even tried to run the links on ChatGPT, which confirmed they were legitimate. If people feel stupid for falling for this, they should know that it is not their fault; everything initially seemed legit. I later discovered that the first test I did was a requirement for UN workers,” Zahra added. She is currently job-searching while working at a friend’s law firm. Her near-scam experience has made her more vigilant; she now double-checks every opportunity before applying.

A successful extortion

In 2024, Fadila Mahmoud*’s cousin called to tell her about a job opportunity at Mentor Mothers, an initiative working towards preventing mother-to-child HIV transmission, and she was ecstatic to apply.

The initiative was under the Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS in Nigeria (NEPWHAN), which has an office at the Kaduna Ministry of Health in the country’s northwestern region. The only catch was that the job ‘required’ a payment before processing. She and her sister didn’t hesitate to raise the money.

“I called the man supposed to be in charge, and he assured me of a job opportunity. All I had to do was pay ₦150,000 in instalments, and the job was mine,” she recounted. However, the requirements didn’t end there; a percentage of their salary was expected every month.

Before starting the job, she and her sister paid an initial fee of ₦75,000. They were then expected to pay the balance within the first three months. A monthly deduction of ₦15,000 from their salary was also required. This included ₦5,000 labelled as ‘miscellaneous’ fees, which was deposited into the team leader’s account, and ₦10,000 that went to a coworker’s account, allegedly the sister of the person who referred them for the job. This arrangement made it difficult to identify the actual beneficiaries of these payments.

HumAngle examined the bank statements and confirmed records of the transfers that were made within those months.

Nigeria, which is said to have one of the highest misery indices globally, has seen an unemployment and inflation rate from 30.5 per cent in the third quarter of 2023 to 36.9 per cent in the first quarter of 2024. This situation is a serious concern, especially considering that the World Bank estimated in 2023 that 87 million Nigerians lived below the poverty line. Additionally, the removal of the fuel subsidy and the resultant cost of living crisis have further exacerbated this crisis.

“Since we needed the job, we agreed to the terms and got the job after a month of payment,” the 23-year-old explained. They signed a contract for the job, but it said nothing about the payment arrangements.

Her responsibility was to orient HIV-positive pregnant women and guide them to the hospital to obtain their medication during community outreach programmes. Each team is assigned to a specific hospital. “We attend antenatal days, sometimes twice a week,” she told HumAngle.

Things changed, however, when the company announced a salary increase from ₦75,000 to ₦120,000. The man who offered them the job demanded that they increase the monthly payment to ₦20,000, making a total of ₦25,000 monthly. HumAngle saw a record of the text that communicated this to her.

“The work was supposed to be contract-based; they assured us that we would be retained for two and a half years and our contract would be renewed for another two and a half years.”

Seven months later, however, Fadila said the head of the Kaduna Mentor Mothers branch called five of them to his office and explained that he had been contacted by the Abuja headquarters that the project they were hired for had been ‘put on hold’ for now. His explanation did not convince them. He also didn’t reference the monetary arrangement, suggesting he knew nothing about the unofficial contract.

“We thought that what they said was not true, and they had other reasons for doing so. At first, we suspected they might want to sell the job slots to others,” she said. Fadila also claimed three of the five people whose contracts were ‘terminated’ had purchased their job slots.

However, HumAngle found that the reason was unlikely. Mentor Mothers had to downsize as a result of funding cuts, according to a senior employee, who asked to be anonymous. HumAngle contacted the NEPWHAN Coordinator in Kaduna State, Bala Sama’ila, for his response to the allegations. We followed up for over three weeks but received no tangible response from him. When we reached out to inform him that we would go ahead with the story, he threatened a lawsuit, distancing himself from the allegations, without offering any explanation as promised.

He also asked HumAngle to share the identities of our sources with him, a request that goes against journalistic ethics and the principle of source confidentiality. “As far as I am concerned, I want to distance myself from all the allegations. Finally, I am not aware of the allegations,” he said in a snappy message sent to HumAngle.

The system is complex

A conversation with a colleague also made Fadila realise that there could be more at play, as she learned that the job slots were ideally intended for HIV patients rather than healthy workers.

Mentor Mothers was initially designed as an empowerment programme for women living with HIV to provide them with the knowledge and skills necessary to educate and emotionally support other mothers living with the virus.

HIV patients experience economic hardships due to medical expenses, loss of income, and an inability to work. A study conducted in Oyo State, South West Nigeria, reveals that female HIV patients are more likely to lose employment opportunities, with a ratio of 24.3 per cent of women affected compared to 9.5 per cent of men. Assigning jobs intended for HIV patients to healthy individuals further exacerbates this disparity.

“Normally, they would tell you not to speak about the monetary arrangement to others to keep it ‘under wraps’ and one of the coworkers even claimed to my sister that the money she was paying them was higher than what we were paying,” Fadila explained.

She felt betrayed and deceived over her job loss. However, she is not the only one being scammed by a seemingly legitimate job.

Habiba Shehu* also faced a similar experience with Mentor Mothers. She paid for a slot, but it did not lead to a job offer. It took several months before she received her money back. At 28 years old, she was waiting for her National Youth Service posting in 2024 when she received a job offer.

“My cousin called me about a job opportunity that her in-laws had sent her. However, they mentioned that I needed to pay ₦75,000 for it. I borrowed the money from others and managed to gather it on time,” Habiba told HumAngle.

The man assured her about the job, providing the requirements he had previously given to Fadila and her sister. They sent her an appointment letter shortly afterwards, with the man claiming that Habiba had taken someone else’s slot because of the high demand. However, after three months, he called her to say that while others had gotten the job, she was unfortunately no longer on the list.

“I asked for a refund of my money. He asked for a one-week extension and then two more weeks. But when he did send in the money, he sent only half of it and asked for more time,” she said.

After he began to evade them, they resorted to calling and threatening him. He became scared when they threatened to take him to court and refunded the full amount. Currently, Habiba is completing her NYSC, and she hopes the labour market will be much kinder by the time she finishes.

Eunice Thompson, a corporate lawyer and expert in HR and compliance, sheds light on the legal implications of these schemes.

“The Advanced Fee Fraud Act states that everyone who collects money for something they can’t deliver can be jailed for up to seven years,” Eunice noted that people can sue the individuals and organisations responsible for this scam. The ICPC Act for public service jobs also counts asking someone to pay for a job slot as an act of corruption, which can lead to prosecution. But this also means that the people paying for the jobs are also taking part in the illegal system.”

The lawyer adds that people who have been scammed can get justice by gathering evidence and acting swiftly. She encourages people to collect documentation of every conversation they have with the person, including screenshots and other forms of documenting interactions.

“There are Ministries of Labour and employment offices in many states where these issues can be reported. If money has been collected, it becomes a criminal case, which can involve the police and the EFCC. In case you need legal aid in terms of resources, the Legal Aid Council of Nigeria or National Human Rights Commission or other nonprofit organisations can help,” she explained.

Hope beyond the shores

Haruna Shuaibu*, who has done jobs throughout his adult life, is another victim of the exploitative system.

After graduating from secondary school in Zamfara, things stagnated for him. He didn’t have the means to continue his education and was desperate for better opportunities. His desperation made him move to Abuja, the Federal Capital Territory, hoping to get a better chance at life. However, things didn’t go as planned, and he had to work other menial jobs to survive.

His first business in this new city was borehole repair, and he also sold carrots on the side. Eventually, these jobs were not sustainable enough to keep him in town, so he relocated to Kaduna State in 2012. With little to sustain himself, he started to hawk sugarcane in a wheelbarrow, but soon after, his brother-in-law employed him to work as a tiler under his business, where they got contracts to fix tiles in people’s homes.

“I worked with him for three years, but realised in 2015 that I could enter the tricycle business (locally known as Keke Napep). This has been the job that has sustained me for many years, during which I was able to start my own family,” Haruna said.

For the past few years, Haruna has used 23 tricycles, most of which he rented from others. He pays the owner ₦3,000 from his daily proceeds in his current arrangement. He also manages the tricycle’s daily maintenance while the owner handles significant repairs.

This job does come with its challenges. The tricycle is constantly at risk of being stolen, as it has happened to him before. However, this business has also introduced Haruna to what he believes could be a pathway to a better life.

A kind encounter with a passenger led to his employment as a driver for a family. This connection is what introduced him to the possibility of leaving the country.

“I worked with them for a few years. Before I learned that her husband helps process job opportunities for people abroad, I had received another job offer,” he recalls. Haruna had never considered leaving for greener pastures. Still, after an incident rendered his tricycle unusable, preventing him from working for almost four months in 2023, he had to explore other possibilities.

“My friend encouraged me to consider leaving with him as he tried to get opportunities out of the country. Someone connected us with a woman who was said to have connections. We were made to process our international passports and undergo a health screening,” he recounts.

However, the plan fell through due to financial constraints; the agents expected them to pay almost a million naira. They tried negotiating the terms, hoping to pay when they reached there, but they disagreed.

The opportunity was said to be in Baghdad. The woman collected their passports for a while, claiming she would help them process the jobs to the best of her abilities. “When we discovered that it wasn’t going to work out because the woman herself was leaving the country, we simply collected our passports back, ” he says.

Along the way, Haruna received other opportunities to work in Libya but refused after hearing the horror stories about such trips. Human traffickers have been operating in Libya since 2014, facilitating the smuggling of undocumented migrants across the Mediterranean Sea and causing many to lose their lives. This situation frightened Haruna, making him wary of such opportunities. Shortly after, the woman he worked for learned about his attempts to travel. She then informed him that her husband had connections with individuals who handled these opportunities.

“They said that the problem was that you have to pay first, due to previous bad experiences, where people switched jobs and secretly left the company they were assigned to, without paying their debts to the people who processed the opportunities. This had forced them to start a strict payment before service policy,” he tells HumAngle.

The husband in question later contacted him in 2024 and said they had an opening for a bike delivery man in a factory in Qatar. They thought he would be a perfect match for the job since it was similar to the one he was already doing. But he still wasn’t financially able to pay for it.

Haruna has been saving up for the next opportunity. He recently started the procedure for a potential job in Saudi Arabia, but he is invited to an interview in Lagos State before everything is set. This opportunity required a ₦500,000 processing fee, which he managed to save up.

The term “Japa,” which comes from the Yoruba language and means “to flee,” is commonly used to describe the mass outmigration of Nigerians seeking better opportunities abroad. Research indicates that various socio-cultural, political, and religious factors, such as high unemployment rates, insecurity, and poverty, fuel the Japa phenomenon. This trend has resulted in a significant loss of talented individuals. For example, Nigeria’s medical system has experienced a substantial drain of doctors, leading to a troubling doctor-to-patient ratio of approximately one doctor for every 30,000 patients in certain regions.

“I am not sure which kind of job it is, but I know it involves working in a factory,” Haruna says. There weren’t a lot of details given to him about the job in question; the agents claimed that he would get more information when he went for the interview and medical screening in Lagos. The person he is communicating with informs him in Hausa that his potential job is at a ‘waya’ factory, which could translate to either a phone factory or a factory dealing with cables and wires, leaving him unsure of what the job description entails.

The job opportunity is said to last two years. “In those two years, you are expected to pay the company a certain agreed-upon amount from your salary. When the time expires, you can choose whether you want to leave or stay,” he explains. The details of the payment plan have not yet been communicated to him.

The company informed them that their potential monthly salary may be up to ₦800,000. There are many risks to irregular migration such as kidnaping and theft, exploitation and abuse, physical abuse, rape, torture, deportation from the countries, and enslavement.

HumAngle found that most of the supposed opportunities are for drivers or delivery men, who usually go to men, with occasional opportunities more suitable for women. The agents, who mostly work as middlemen, require a down payment before travelling, with a few exceptions.

Bashir Abba*, an agent between job seekers and companies, claimed, “There are many challenges. Sometimes, we get opportunities for people who refuse to pay back after getting the job. Other times, people ask for favours, and when we get them opportunities, they disappear and leave us to bear the cost.” This, among other reasons, is why he is reconsidering leaving that career path.

For Haruna, the reasons for leaving are massive. “I have many reasons for wanting to leave. I wouldn’t even go anywhere if I got tangible start-up money for my business. I would rather stay here and start a business instead. I am pretty sure there would be something I can do.”

Haruna expects to travel before the year ends, hoping to make enough money there. However, he is still sceptical, mainly due to the unclear details. He hopes that if he does travel, he will get a chance to change his financial status in Nigeria when he returns.

A BBC documentary released in April highlighted how scammers steal thousands from unsuspecting people under the guise of job opportunities and fail to deliver on those opportunities. Kelvin Alaneme, a popular Nigerian medical practitioner, who claimed to have helped 5,000 migrants relocate to the UK, was at the centre of this scheme. One of his victims claimed to have paid him £14,000 (₦29 million), after which the job didn’t materialise.

Payment made, refund denied

The extortionate job slot system thrives because many young Nigerians are desperate, as in the case of Ahmad Hassan*, who expected to get a job immediately after graduating from Ahmadu Bello University in 2015, especially with his skill set. However, 10 years later, like many other young Nigerians, he struggles to find footing.

Ahmad found himself constantly filling out job applications and delivering his CV to many who promised to help, but his hopes were crushed continuously as none of these opportunities materialised. “I had to find other ways to survive, so I ventured into selling clothing and jewellery. But that business soon went under as people always took things on credit,” he laments. The situation made it difficult for the 34-year-old architect to sustain his business. With few other opportunities in the saturated architectural field, Ahmad believed that buying a job slot or opportunity was his best alternative.

In 2022, his friend connected him to someone who was said to have a connection to the government and was offering a Central Bank job. Before that, Ahmad had tried to buy a Prisons Service job slot for ₦200,000 in 2021. He didn’t get the job, nor did he get his money back. He said the CBN opportunity came from a more ‘trustworthy’ source, and the total amount to be paid was ₦3.5 million with an initial deposit of ₦1.5 million, after which a balance of ₦2 million would be paid upon documentation.

“I did my due diligence by making inquiries about the process, people involved, duration of time it takes for the appointment to be ready and any other thing I was aware of. After I was satisfied with my inquiry and the assurance I got from those involved in finding a government civil service job, I made the payment.”

The initial contract also specified that payments would be refunded three months after they were made if the job did not succeed. However, Ahmad’s hopes were once again dashed when the opportunity he struggled to get money for didn’t manifest. He was left to keep asking for his money back, but the people kept requesting time extensions to source the funds.

Recruitment fraud in Nigeria has evolved into a multi-million naira industry with thousands falling victim to the schemes, leading to financial losses and mental distress. Earlier this year, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) arrested a scammer who posed as a staff member at a house and defrauded job seekers of an estimated ₦22 million. Besides fake job advertisements, these scammers request an upfront payment or pose as agents from reputable organisations.

Eunice, the lawyer, explained that selling jobs is illegal especially government jobs which violates the Civil Service Rules, ICPC Act, as well as the Nigerian Constitution, and people who are caught can either be jailed, released from service or forced to pay money back- and as for private sectors, this also violates the Labor Act, the Advance Fee Fraud Act, and the Anti-money Laundering Act. She believes that the lack of access to information on the dangers of buying jobs, as well as the desperation that pushes many job seekers to make that decision, further perpetuates the circle.

“I got ₦700,000 back in 2023, and only got the rest back last year in two instalments, ₦500,000 and then later on ₦300,000 was returned to me. I was even among the lucky ones to get their money back, as some people got nothing in return,” Ahmad said.

Ahmad felt he had few options despite the challenges and risks, as other businesses he ventured into eventually failed for one reason or another. Sometimes, he gets the occasional architectural gigs that bring in some cash. Then, a friend informed him that there was an opening for a job with the National Drug Law Enforcement (NDLEA), with an initial deposit of ₦100,000 required. However, even paying the money on time did not guarantee getting the job; he still struggles to get his money back.

“They only refunded me ₦50,000 in 2023, and I still haven’t gotten the rest back. When you don’t have options, you have to crawl your way up, and I know people who got jobs in the Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS) and the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) through this process,” he added.

Another challenge he encounters is age limitations, which are a barrier to opportunities for which he is qualified. In 2023, Nigerian senator Patrick Abba Moro called for the dismissal of age limits, which serve as a discriminatory factor in the employment system. This limit has led to desperate Nigerians falsifying birth dates to meet this criterion. Chapter 4, Section 4 (2) of the Nigerian Constitution states that all citizens have the right to be free from Discrimination.

Ahmad has not given up on finding new business ventures or applying for job opportunities. He is not unwilling to try finding a job through this process, especially since he has seen it materialise for others, and other alternatives don’t seem to be working.

Like Ahmad, who almost tore his pocket to pay for non-existent job slots, Linda Joseph can never forget the man who taught her mother for a few years in secondary school. Now, his identity has become the man who defrauded her family with a fake job offer at the Ikeja Airport, Lagos State, southwestern Nigeria. His history with her mother was likely why her parents trusted him and didn’t scrutinise his offer deeply.

“He told my mum he worked at the Ikeja Airport and had an open position, but his boss requested a ₦100,000 fee. My mum paid in two tranches, and the last we heard from him was after the second payment landed in his account,” she says, noting that from 2019 till date, the man was nowhere to be found and no job materialised.

When this happened, Linda worked in a privately owned organisation in Lagos. Although she loved her job, she was usually up working in the middle of the night, which affected her sleep schedule.

“I won’t say I was searching for other opportunities heavily at that time, but the lack of sleep bothered me and my parents,” she explains.

After graduating from the university in 2014, Linda endured the treacherous job market. The 30-year-old has worked in the private sector and now works at a nonprofit, where her passion lies. Over the years, she has volunteered, interned, worked as a consultant, learned baking, and worked as a writer for a short while.

“In retrospect, I do not think he worked in any airport. My mum has since ‘left it to God’ in her usual manner, but I? He better hope I don’t see him anywhere on the streets because he will vomit my 100k.”

In the meantime, she is learning a skill pertinent to her career and hopes it will open up room for bigger opportunities.

Eunice pointed out that the problem with Nigerian laws is in implementation. Sections 23 to 24 of the Labour Act particularly seem good on paper. “There is a law that every recruitment organisation must first be licensed by the Ministry of Labour, but a lot of them operate illegally without registration. A lot of our processes and systems also use paper trails, making it difficult to trace,” she noted. “If enforcement is tightened, the bodies responsible can identify the people running these scams. For instance, in Ghana, the board department publishes a list of licensed employment private agencies online.”

The lawyer believes this would help curb some of the employment scams many desperate job seekers fall victim to. She also thinks in the adoption of a National Job Portal for public service jobs, which is currently being done in other countries like Kenya, as well as public awareness, with national orientation to educate people on these scams, especially using already existing schemes such as NYSC, can help put an end to these issues.

After quitting a toxic job, Zahra Usman fell victim to a scam promising a role at the UN, only realizing it was fraudulent after being asked to pay for a certificate.

Similarly, Fadila Mahmoud experienced an extortionary job process at Mentor Mothers, where she and her sister agreed to a salary deduction and additional payments. This highlights the prevalent issue of job scams in Nigeria, worsened by unemployment and poverty, with schemes often going unreported due to a lack of proper infrastructure and societal shame.

Haruna Shuaibu and Ahmad Hassan are among those deceived by false promises of lucrative job opportunities abroad and government jobs, respectively. Haruna tried to embark on an international job venture only to encounter payment scams, while Ahmad fell to a scam involving a Central Bank job and faced challenges reclaiming his funds. Furthermore, Linda Joseph faced deception by a trusted individual with a fake airport job offer, emphasizing the impact of scams on Nigerians desperate for employment due to systemic issues and the need for stronger legal implementations to prevent such frauds.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter