The Everyday Misogyny Faced by Women Healthcare Workers in Nigeria

From hospitals to pharmacies and laboratories, women working in Nigeria’s healthcare sector endure dismissal, bullying, harassment, and disrespect from colleagues, patients, and the families of those they treat. It takes a heavy toll on their emotional well-being and careers.

It was not passion that pushed Rahimat Ola* into the medical field. She had dreamed of becoming a writer, but her parents decided they wanted her to be a medical doctor because that was where the money was. After three years, from 2011 to 2013, of failed attempts to get into medical school, she settled for a degree in science laboratory technology with a speciality in microbiology. She took that option because it was the closest to her parents’ dream.

But her story was not a tragedy, because she soon became interested in it and started nursing another dream of becoming a medical researcher.

“I wanted to make so many contributions to the world through medical research and just help people,” she told HumAngle. “I rewrote the exam again and got admission to study nursing, but I didn’t take it because I had already fallen in love with medical research.”

During her Student Industrial Work Experience Scheme (SIWES) placement at a clinic, Rahimat’s dedication was such that she continued to volunteer even after the official programme ended. It was during this period that she was involved in an accident that gravely affected her.

“There was this patient who obviously looked sick, but he did not mention he was afraid of needles, so while trying to take his blood sample, he started struggling immediately. The needle pricked him, and as a result, I got pricked too,” she recounted.

Rahimat reported the incident to her senior colleagues immediately, and they asked her to wash her hands. At first, she thought little of it, until the test results for the patient came back showing he had Hepatitis C, a bloodborne virus transmissible through blood.

She tested for the virus after three months, then six months, and a year later, all came back negative. But soon afterwards, she began to notice symptoms, such as cramps and skin sensitivity. The doctors she consulted insisted everything was fine until her mother went back there with her and kept pushing for more tests. It was then that the result returned positive.

What followed was not only a medical battle but a social one. After she disclosed her condition to the head of the lab, believing it was the right step since she had contracted it at work, her medical information leaked. Stigma soon crept in, with rumours and insinuations circulating among her colleagues. “One of the lab scientists who once made romantic advances towards me started to make sexual insinuations,” she said.

Even after she explained that her doctors said that the earlier negative results might have been due to low viral load at the time of infection, some colleagues refused to believe she had contracted the infection in their lab.

Rahimat said that the stigma and gossip at her workplace had a serious impact on her.

Such disinformation is a common tactic used to distort, dismiss, and distract to stifle the voices of people, especially women. Gender disinformation is particularly widespread and perpetuates a culture of silence and shame, and also creates room for misogynistic tendencies to thrive. In Nigeria’s healthcare sector, where women make up about 60 per cent of the workforce sector, these dynamics are especially pronounced.

For Rahimat, the whispers and innuendos carried an old, familiar sting. Long before her diagnosis, she faced unwanted sexual advances from some lecturers at a medical school in northern Nigeria.

A survey of over 30,000 tertiary education students in Nigeria revealed that about 37 per cent of the respondents have experienced a form of sexual violence, with female students reporting twice as many incidents as their male counterparts.

“I knew it would have been worse if my father had not been a lecturer in another faculty in the same school. The moment they learned that, they left me alone, but some persisted,” she said.

One lecturer, she recalled, sexually harassed her throughout her four years in school. By her final year, while she worked on her thesis, the harassment turned into victimisation.

“He promised me he was going to disgrace me during my thesis defence, and he attempted it. During the defence, before any other lecturers could speak up, he started asking questions he thought I could not answer, but unfortunately for him, I answered the first two and told him the last question was beyond the scope of my study and would research more,” she said.

At times, even women lecturers blamed her for the harassment, suggesting she did not wear her hijab “properly” for a Muslim, even though the university was not a religious institution.

After graduating, Rahimat hoped such experiences were behind her. But during her National Youth Service in 2019, while working at a university lab in Oyo State, southwestern Nigeria, she faced yet another round of gender prejudice. At first, everything went smoothly, but seven months into her one-year service, the head of the lab started to make sexist remarks, claiming women were lazy and that he preferred male lab technicians.

Research shows that deep-seated beliefs about gender roles in work environments add to the systemic barriers that make it challenging for women in the workforce.

Rahimat said she would simply ignore those comments and focus on her job. This shift in her manager’s attitude coincided with the arrival of another male corps member in their team. Tension grew after her new colleague found out that her ₦30,000 stipend was higher than what he received. The school did not recognise him as a lab technician, so he earned only the extra ₦6,000 paid by the state government to corps members.

Rahimat explained to him that the extra ₦30,000 was paid to her directly by the school, not the laboratory, and that another colleague in the same role as hers was receiving the same amount. Still, the explanation did little to ease the resentment. Soon, the male colleague began spreading rumours that she was being paid more because of personal connections.

The rumours got so serious that Rahimat was summoned to the administrative office.

“I could remember, the man there said to me that if I wanted to do ‘stuff,’ I should not have done it that obviously. I told him I did not understand what he was saying, and he started to backtrack. I told them that whatever issue there was with the payment was their fault and it had nothing to do with me. Apparently, by ‘stuff’, they meant I had seduced someone to get favours, when in reality I had never even met anyone connected to the organisation before I was posted .”

Her service year was her first time in Oyo, as she grew up in northern Nigeria. She had moved there alone and did not know anyone, like most corps members.

Following the administrative summons, she was instructed to refund the extra amount she was being paid. She asked them to put the instruction in writing, and that was when they let her be. At the end of that month, the management announced that she and the male colleague would be transferred to the university’s science laboratory department, where they would work as teaching assistants.

However, Rahimat soon learnt that she was the only one who was reposted, and the male corps member was made to retain her position, a move she suspected had been the plan all along.

She felt out of place in her new role and believed the lingering rumours affected how she was treated, but eventually, colleagues began to warm up to her. However, she did not receive payments, as the management claimed they were deducting her “overpayment”.

“I felt hopeless and discouraged,” she recounted. “I felt like a nobody in the system, and it bothered me that I couldn’t change the system. It felt like it was not a safe space for me to be, and I did not want to deal with the medical field anymore.”

Determined not to give up, Rahimat attempted to start her postgraduate studies to pursue her dream of becoming a medical researcher. However, when her sister fell sick with cancer, she became her sister’s primary caregiver, putting her ambitions on hold.

This rerouted her career path. She took a job as an editor at a publishing house and sold books on the side to support her sister’s medical bills. In 2021, she started a psychology degree.

Now 29, Rahimat said she is content with her writing career and free from the complications of being a woman in the medical field.

‘Not so casual’ misogyny

Rahimat is one of many women in medicine who have faced gender discrimination at work. Janet Adam*, a medical doctor in the country’s North West, initially thought she had escaped much of it, until she examined her career more closely and realised that these experiences were normalised.

For women doctors in Nigeria like Janet, this discrimination often manifests through sociocultural biases, lower pay, and a lack of professional respect. Patients and their relatives sometimes refuse to recognise women as doctors, addressing them as nurses even after being corrected. “I have had several encounters,” she said. “I am a very vocal person, and I have actually changed it for patients.”

According to Eunice Thompson, a labour lawyer and HR and compliance expert, such behaviour can be more than just disrespect; it can be a workplace rights violation.

“Women can seek justice when they experience harassment, abuse, or injustice in the workplace,” she said. “In the course of the work I do, I noticed bullying, verbal abuse, and harassment are a common experience that women go through, and this is a violation of their right to dignity and a threat to their mental health, safety, and career.”

The lawyer advised women to document incidents by keeping a private log of events using screenshots or recordings on their phones, keeping track of the dates and who was present during the event, and if the facility has a HR professional or a complaint channel, they should utilise it even if they do not trust the system, as submitting it in writing is a form of documentation itself. She added that they should request an acknowledgement of the receipt of the complaint.

Janet believes much of the treatment she has faced stems from her gender, noting that male colleagues rarely endure the same. The pattern, she says, extends to women in other departments, like administrative workers and sometimes even to female patients.

Sometimes, this misogyny for female doctors translates into patients dismissing their diagnosis or professional advice and seeking a second opinion from a man, she explained. “Even if the male doctors asked if you [referring to a female doctor] didn’t inform them beforehand, they would say you did, but [they] still needed to confirm,” she told HumAngle.

The disrespect also comes from colleagues. During a ward round early in her career, she asked in Hausa about “the boy” usually present by a teenage patient’s bedside. A senior male colleague, with whom she’d had prior tension, berated her for using the word “boy,” dragging out the criticism “unnecessarily”.

“I don’t think he would have said anything if I [had] asked about the girl staying with the patient, as it is normal to see women, even doctors, being addressed as ‘ke,’ but they never address male doctors as ‘kai”,” she noted. In Hausa language, the informal ‘hey you’ can be seen as disrespectful, especially when there is a professional relationship.

Janet said she cautioned the colleague not to disrespect her in front of her patients again. The consultant present did not interfere in the matter.

Years later, the lack of professional respect she experienced from colleagues would echo in her interactions with patients’ relatives. In 2024, while working at an orthopaedic hospital in the same region, her colleagues informed her of the son of an elderly patient, who was known to throw his weight around, constantly referencing the fact that he came from Europe to take care of his sick father.

“The day I resumed work, I went to check on the patient, but the son kept interrupting me, asking unnecessary questions. I told him I could not comment because I hadn’t fully read the patient’s folder and had just come to check in,” Janet recounted.

However, he ignored her explanation and continued with the questions. When Janet turned to monitor the nurse who was taking the patient’s blood pressure, the man suddenly began to yell at her. “He accused me of being disrespectful,” she said.

He eventually asked her to leave the room. As she walked away, the patient’s son started to come menacingly close, as though about to hit her. When Janet asked him if he wanted to slap her, he demanded to know what she would do about it if he did. Due to the threat of violence, she reported the incident to her line manager, saying she would not treat the patient again.

The confrontation didn’t end there. The man followed her to the reception, continuing to shout. Frustrated, Janet said she shouted back at him, prompting him to bring out his phone to “record the disrespect”. “I slapped the phone from his hand and told him he could not aggravate me and then try to record my response,” she recounted.

It was not the first time she had felt the need to use extraordinary measures to tackle situations like that. “Even in medical school, I ensured not to tolerate things like this,” Janet said.

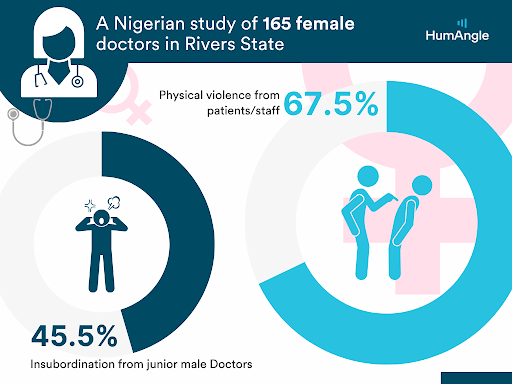

A 2023 study by the Nigerian Medical Association shows that 45.5 per cent of 165 women doctors in Nigeria’s South South have experienced physical violence from both patients and/or other staff in their work environments.

Twenty-five-year-old Halima Bala*, who is currently practising in Katsina, northwestern Nigeria, echoes Janet’s experience of being bullied by a patient’s relative.

“A nurse and I were the only ones on duty, and the patient’s relative, who was a big man, started shouting at both of us because there weren’t any empty bed spaces, and we had to be cautious because we didn’t know what he might do to us,” Halima recounted. “He mysteriously became calm and civil when a male colleague came to interfere. I was so upset. I even felt like I didn’t want to treat his daughter anymore, but my anger softened when I saw the state the patient was in, and I believe there is no patient I should refuse to see.”

When incidents like this happen, the hospital can either take the doctor off the case or, in more severe cases, which Halima has never witnessed personally, choose not to treat that patient. Yet, in her experience, the default approach is to side with the patient. When the hospital apologised to the man who had disrespected her instead of holding him accountable, Halima said it reinforced her understanding of how deeply entrenched and unjust misogyny can be.

However, she noted that these experiences did not deter her; if anything, they encouraged her to excel at everything she does.

Eunice said women can report such abuse to professional bodies like the Medical and Dental Council or Nursing and Midwifery Council, and if internal channels fail, they may go public or seek community support to push for accountability.

“If harassment is verbal or slanderous, people often dismiss it, but it is harmful, especially when you can prove it’s targeted and persistent. Record it and write exactly what was said, and get a trusted colleague who can serve as a witness or offer support, and you can sue for defamation too,” the labour lawyer added.

‘As a woman, you should…’

When 54-year-old Hadiza Husseini* chose to study pharmacy out of her love for helping people change for the better, she assumed it would be less consuming compared to being a doctor, hence she would be able to raise her family. While she can not recall experiencing gender discrimination and assault during her undergraduate studies, Hadiza said she came face-to-face with the challenge after she gave birth to her third child.

“I had a very misogynistic boss at that time, who would constantly make sexist comments about my womanhood and motherhood. I ignored him, but one day I completely lost it. I told him to leave all the work for me that day, and he would see that my gender or baby would not stop me from doing every work that was supposed to be done,” she recalled.

He stopped bothering her afterwards.

However, the impoliteness did not end. Years after she became a chief pharmacist, making her the third in command in her department at that time, her deputy director, who was a man, turned to her after a meeting one day and asked her to clear the dirty cups they had been drinking from since she was the only woman in the room.

“I was shocked and dumbfounded and struggled to wrap my head around it,” she recounted. “Even my junior colleagues turned to stare at him. I instinctively said, ‘What?’ and he said he thought I wouldn’t mind because I was a woman and I would enjoy doing it.”

Most of the people who drank from the cups were not only younger but also much lower in rank than her, and they were all still in the room.

Since then, there have been several other acts of gender discrimination that Hadiza has challenged. “There are people in my office who call me the minister of women’s affairs because I do not allow anyone to disrespect a woman in front of me,” she noted.

Research shows that workplace conflict, which could be a product of power imbalance, gender discrimination, resource allocation, transgenerational strain, and interprofessional relationships, affects the experiences and well-being of Nigerian medical practitioners.

In Nigeria, there is no strong anti-workplace discrimination law, but there are still legal protections that are available. Eunice, the labour lawyer, noted that Chapter 42 of the Nigerian Constitution, which states that nobody should be discriminated against based on sex, even if you are the only woman in the room or team, is one of those laws.

She also cited other laws that could be useful, such as the Violence Against Persons Prohibition Act (VAPP) and the Laws of Torts, which recognise psychological abuse as a form of violence.

“The International Women’s Rights Treaty is also a powerful advocacy tool, although it has not been fully domesticated in Nigeria. However, a law is only as useful as a system that enforces it, and enforcement is weak in Nigeria,” Eunice noted. “That is why we need more legal knowledge alongside community power and support. The fact that these things are common does not make them right. Women deserve to be treated with dignity and fairness.”

Bullied yet underpaid

Globally, nursing remains a female-dominated profession, and Erica Akin* says her nine-year career has been marked by frequent bullying from both healthcare practitioners and patients alike. “Nurses on duty get blamed for every problem in the hospital, even while it is glaring that they are not at fault. If a lab scientist does not come to get a patient’s blood for investigation, or if the patient waits too long in line to see the doctor, the nurse gets blamed,” she said.

Erica, now 34, became a professional nurse in 2016 after passing her qualifying exams on her first attempt. Despite the rigorous training and pressure during her studies, she found the workplace equally challenging. She says bullying is normalised in the sector, leaving her feeling unappreciated, and it often worsens when she stands up for herself.

“It only challenges me to be smarter and more efficient at my job to avoid disrespect of any kind,” she told HumAngle, adding that she is also concerned about how nurses are significantly underpaid in the healthcare sector.

While her federal-level salary is higher than in private facilities, she believes it still undervalues nurses’ workload. “The startup salary for the [federal government’s] Consolidated Health Salary Structure (CONHESS 9) is about ₦215,000, while private hospitals may pay ₦30,000 to ₦60,000, depending on the facility,” she said.

‘Twice as hard’

“The medical system is very toxic,” Jamilat Abdulfattah, a medical practitioner who works in Kwara State, North Central Nigeria, claimed, adding that earning her white coat has not been an easy ride. “People respect male doctors more than females, and even other health workers vividly show dislike towards you because you’re a female.”

The 26-year-old sees this as a result of the general misogynistic notion that women cannot perform as well as men. Oftentimes, this makes her feel underappreciated and sometimes pushes her to work twice as hard as her male colleagues just to get appropriate respect; on some days, it means going to work early.

“I observed that my male colleagues can just slack off, and people still respect them as doctors,” she said. “As a woman, I am always on edge and pushing myself to go the extra mile so I won’t be seen as less than, and every mistake is ascribed to my gender.”

“However, I don’t let it get to me. I call out misogynistic behaviour most time. But when it’s coming from a senior colleague, I will have to endure because the hierarchical system would not allow me to do certain things, or else I can risk getting kicked out of the system. So instead, I focus on what I can control and let what I can not control go,” Jamilat told HumAngle.

She is hopeful that these irregularities will change in the future.

“Most of us plan to break the cycle of bullying,” she said.

Names marked with an asterisk (*) have been changed to protect the identities of the sources, who spoke on condition of anonymity due to fear of harassment or further discrimination. The names of the institutions where they work have also been withheld.

Rahimat Ola's career journey from aspiring writer to medical field professional illustrates the challenges of gender discrimination and stigma she faced in Nigerian healthcare. Initially forced into the medical field by her parents, Rahimat found passion in medical research but encountered stigma after contracting Hepatitis C at work. Additionally, her workplace was rife with gender bias and gossip, which impacted her job satisfaction and progression. Despite these challenges, Rahimat pursued a psychology degree and shifted to a writing career.

Other women, like Janet Adam and Hadiza Husseini, also faced misogyny in medicine, manifesting through lower pay, lack of professional respect, and unjust treatment. Many experienced unwarranted sexual advances and mislabeling of roles, where patients and colleagues disrespected their authority as doctors and pharmacists. This environment pushed professionals, like Jamilat Abdulfattah, to work harder for recognition and hope for future change. Legal expert Eunice Thompson emphasizes documenting incidents and seeking justice, although enforcement remains weak in Nigeria. Despite hurdles, these women remain resilient and hopeful for a better, more equitable future.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter