The Evasive Funding Channels Sustaining Boko Haram/ISWAP in Nigeria

Beyond the battlefield, the terrorists have governed civilian spaces, collecting taxes, enforcing laws, and offering basic welfare, particularly within their strongholds in the Lake Chad region.

Beneath the violence that has come to define the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) lies a highly organised financial ecosystem sustaining their operations. Fuelled by a complex blend of taxation, extortion, smuggling, and ideological justification, the groups have transformed parts of northeastern Nigeria into a conflict-driven economy.

For over a decade, terrorists have waged war against Nigeria and its neighbouring countries, displacing millions and wreaking havoc on communities. They took control of some civilian communities, collecting taxes, enforcing laws, and offering basic welfare, particularly within their strongholds around Lake Chad.

In recent times, HumAngle has uncovered how these groups have moved beyond the conventional tactics of ransom collection and taxation. They are now tapping into the dark web to generate revenue, exploiting the anonymity of cryptocurrencies to evade traditional financial surveillance. This marks a strategic shift by Islamic State affiliates, especially as the core group struggles with diminished income following its territorial losses in Iraq and Syria.

Beyond the traditional hawala system, which transfers funds informally through networks of trust, terrorist financiers are now leveraging decentralised digital currencies to solicit donations and channel funds. These covert financial pipelines challenge counterterrorism efforts and expose a growing blind spot in the global fight against extremism.

Drawing from interviews with former fighters, security experts, and residents of conflict-affected communities, HumAngle has also traced offline funding methods that jihadist factions continue to rely on across the Lake Chad region.

“Zakat is paid willingly by members and enforced on outsiders,” said a former ISWAP member, who spoke anonymously due to safety concerns. “It is pooled to the Baitul Ma-al (treasury) at the headquarters of the different wilayats.” For the outsiders and non-combatants, the term is referred to as “jizya”, a levy enforced on an individual who doesn’t subscribe to the jihadists’ version of Islam.

The wilayat (smaller territories under ISWAP control) enforcing the zakat and jizya serve as administrative zones modelled after Islamist governance. They function not only as extensions of the Islamic State’s ideology but also as de facto provinces, each led by a wali (governor). At the local level, operations are controlled by an administrator known as an Amir.

The insurgents operate a formal taxation system that draws from Islamic principles but is executed with military precision. Residents pay zakat, the religious tithe, alongside fees for farming, fishing, or conducting trade. Outsiders entering the dawlah (state) are subjected to additional levies.

“Revenues are collected by appointed officials who move around town, villages, farmlands and grazing areas,” the former fighter explained. “The financial records are kept by the revenue collectors.”

Compliance is mandatory. Refusal brings swift and brutal retribution. “Confiscation of assets, jail sentence or capital punishment were the typical sanctions,” he said. “[Sometimes] it could amount to capital punishment.”

Farmers interviewed by HumAngle in Borno, for instance, are required to pay about ₦10,000 per hectare. No one is permitted to begin farming without this payment, and receipts are issued by the group as proof. Recently, that levy has been increased to a whopping ₦50,000, causing some discontent among the people living under ISWAP’s control, reportedly making them defect to the Jama’atu Ahlussunnah Lidda’awati Wal Jihad (JAS) faction of Boko Haram.

To mask coercion under religious legitimacy, ISWAP invokes theological language. Appeals for financial support are couched in terms like isti’dad (preparation for jihad). While donations are said to be “according to your means,” refusal is harshly punished.

“Sometimes businessmen are fined for disobedience, and it’s called a donation,” the former terrorist recalled. “It’s never really voluntary.”

This fusion of religious rhetoric and criminal enforcement allows ISWAP to assert moral authority while wielding authoritarian control. The collected money doesn’t simply enrich individual fighters. Much of it flows into a central Albaitul maal, where it is redistributed across operational and administrative needs.

According to the former fighter, funds are used for multiple purposes: “Weapons, paying fighters, giving stipends to widows and orphans of dead fighters, running health clinics on special days. Even some community services.”

Fighters receive monthly salaries and bonuses during military campaigns. Welfare packages are given to the families of dead fighters. Some areas under ISWAP’s influence maintain makeshift clinics and rudimentary schools, financed from this central pool.

While this may resemble the functions of a state, it is fundamentally underpinned by coercion. Services are tied to loyalty, and taxes to survival.

“Those living in the dawlah see it as normal activity, and forcefully living under the dawlah, they have no strength to make any reaction,” the former member said.

People living under ISWAP-controlled areas are divided into Awam (commoners/non-combatants) and Rijal (contextually meaning fighters). For civilians in ISWAP-held areas, daily life is a constant negotiation with fear. Some comply to survive, and others, especially new arrivals, live in quiet terror.

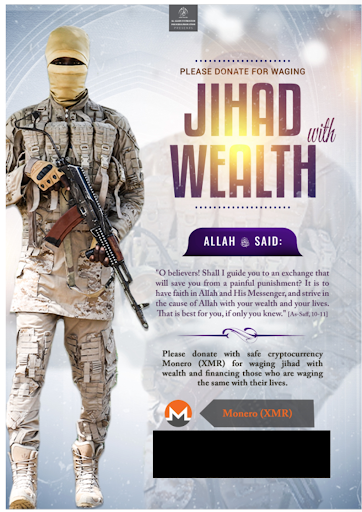

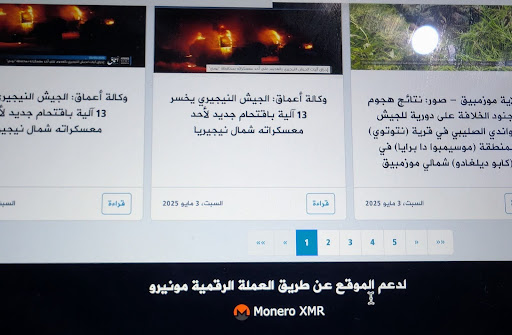

Crypto donations

Nigeria’s status as one of the world’s fastest-growing cryptocurrency markets offers fertile ground for terrorist financing, allowing terror groups like ISWAP to use different platforms, such as Monero, a digital crypto page with enhanced privacy features.

ISWAP’s use of digital currencies in its financial playbook mirrors a broader trend among insurgent groups in Africa and beyond. On the dark web, their propaganda outlets have actively solicited Monero donations, leveraging its anonymity and security.

Monero, developed in 2014 by anonymous creators, conceals transaction details on its blockchain. This has made it the preferred choice for both ransomware operators and extremist networks. The Islamic State’s dark web platforms have openly called for Monero donations in support of insurgent activities. While IS branches like Khurasan have launched dedicated crypto campaigns, ISWAP has yet to do so. However, researchers identify it as a leading crypto user among IS affiliates globally.

ISWAP generates significant revenue, which is often converted into the Monero cryptocurrency platform, which can facilitate anonymous transactions. The preference for Monero stems from its enhanced privacy and security measures, making it challenging for authorities to track and monitor financial flows. By utilising Monero, ISWAP maintains secrecy and evades detection, potentially complicating efforts to disrupt their financial networks and operations.

Smuggling and black markets

In addition to cryptocurrencies, black market operations and regional trade form a large portion of the insurgent economy. Smuggling routes span Nigeria’s borders with Cameroon, Chad, and Niger, facilitating the movement of fuel, food, and drugs.

“Smugglers bring in fuel through Banki and Kirawa [in Borno State],” the former fighter said. “They pay a levy to pass. The group taxes everything.”

Markets within ISWAP’s domain operate under strict supervision. The group controls livestock and fish markets via appointed intermediaries—local businessmen who handle external trade and launder profits back to leadership.

“They are businessmen, but they are also collaborators,” the former ISWAP member told HumAngle. “They don’t carry weapons, but they are part of the system.”

This economic integration has allowed the insurgents to embed themselves into local commerce, making it harder for Nigerian forces and international partners to isolate and weaken them.

The financial engine behind Boko Haram and ISWAP is resilient, adaptive, and deeply entrenched in local realities. It flourishes in the absence of Nigerian state authority, often aided, willingly or otherwise, by community actors.

A 2023 report by the International Crisis Group observed that ISWAP’s economic model mimics state structures and generates steady revenue, especially from taxation of local businesses and traders, noting that defeating this system would take more than military might.

“Breaking the financial backbone of these groups involves restoring legitimate governance and providing alternative livelihoods,” a former staff member of the Nigerian Financial Intelligence Unit told HumAngle, pleading anonymity for security reasons. “As long as they provide services and the state does not, they will retain influence.”

Fifteen years into the conflict, the fight against Boko Haram and ISWAP is no longer solely about military victories, the expert said. It is also about dismantling the systems that keep them alive. In a conflict-ravaged region where the state has faltered, insurgents have constructed a parallel order, founded not only on violence but also on function.

“They are fighting a war, yes. But they are also running a government,” the former ISWAP fighter reiterated.

The Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) has developed a sophisticated financial system in northeastern Nigeria, combining taxation, smuggling, and use of cryptocurrencies to sustain its operations.

These strategies include leveraging the dark web and Monero for anonymous transactions, challenging counterterrorism efforts. They govern areas through systems resembling state structures, collecting mandatory taxes and employing theological justifications to mask coercion.

ISWAP's financial model integrates into local commerce through smuggling and black markets, embedding itself deeply into the region's economy. Despite being an insurgent group, they administer territories, providing services akin to governance.

Successfully disrupting this system requires restoring legitimate governance and alternative livelihoods, as mere military force is insufficient against their entrenched economic and social presence.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter