The Buni Yadi Tragedy: The Boy Who Saw It Coming

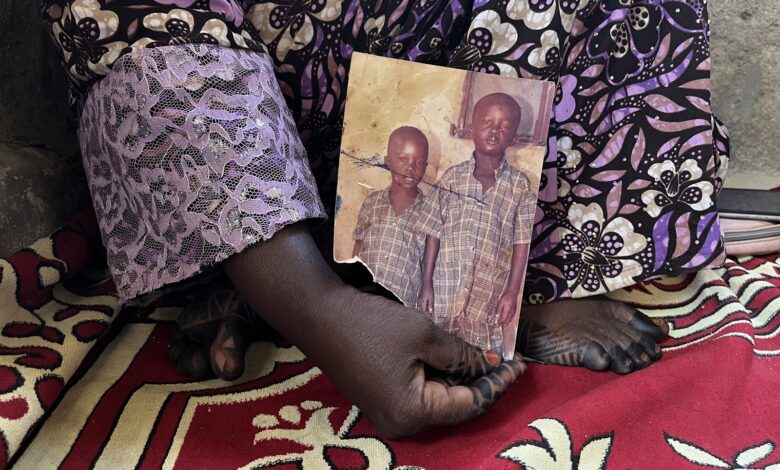

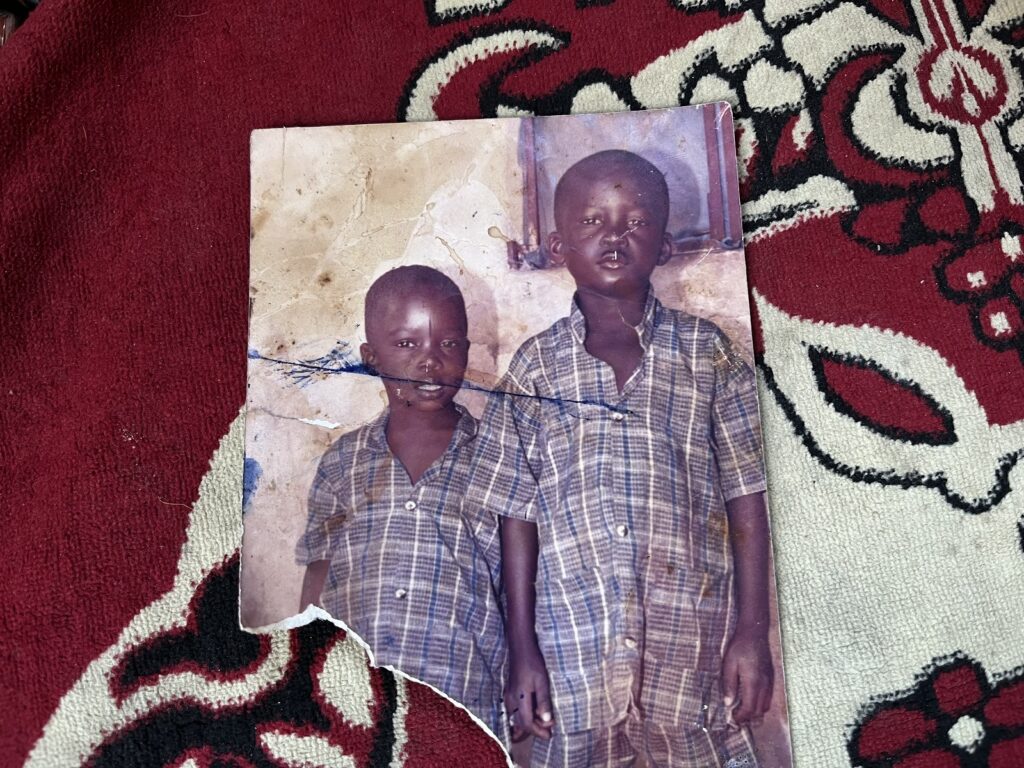

Some months before the 2014 attack on a school in Buni Yadi, 17-year-old Mustapha ran back home from boarding school unexpectedly. Rumours were circling that Boko Haram was about to attack the college, he said. His mother looked into moving her son, but the night the terrorists came, he had already returned.

For a very long time after Fatima Tanko Haruna was given a million naira by the Yobe state government as compensation when her 17-year-old son was murdered in school by Boko Haram insurgents, she left the money in the bank and did not touch it. She could not bear to.

The boy had been murdered in cold blood, and there was nothing in the world that could have brought him back. She did not see the point of the money. And even though her children, especially Ibrahim, tried to explain to her and convince her that it was not payment for the boy’s life, she could never really bring herself to see it that way. The idea of spending the money felt to her like treachery, as though she had accepted that her son’s life was not only quantifiable but could also be paid for.

Months later, Ibrahim tried another approach to getting her to use the money. He asked her to use it for the Hajj pilgrimage to Makkah. That way, she could even pray for her son’s soul, he said. Still, Fatima remained reluctant. But she was no longer as adamant as she used to be about the subject. Sensing he was finally getting to her, Ibrahim contacted her brother to pose the same suggestion. This time, however, her brother advised her to deposit the money in an account that would mean it would be safe. The account her brother suggested offered Islamic finance, meaning it would accrue benefits, without interest. That way, even as she struggled to bring herself to terms with having to use the money at some point, it would keep appreciating. By the time she was ready to use it, she would have more money than she was originally given. She agreed.

She forgot about the money. After all, she was morally opposed to it in the first place. Months later, a family member told her there had been problems with the bank that culminated in the Central Bank of Nigeria having to intervene. She is not entirely sure about the facts of the matter because she never paid much attention to it. And so, to her, the money died a natural death.

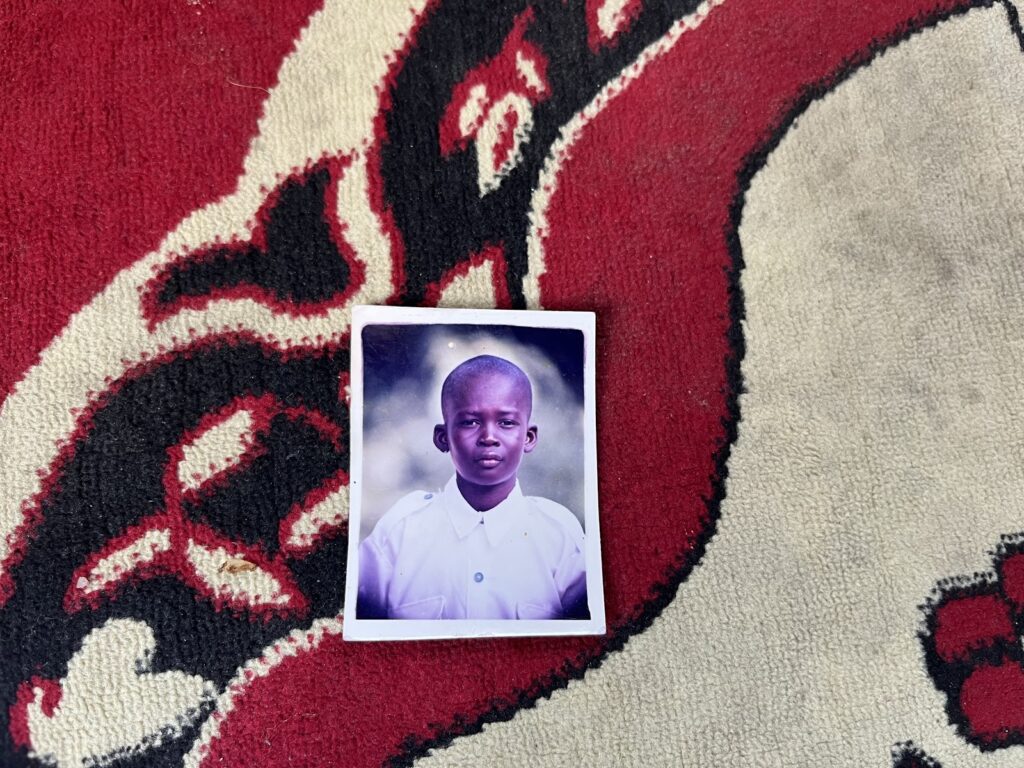

Fatima and her children were based in Monguno, Borno state in northeastern Nigeria at the time her son, Mustapha Abubakar Ali, was killed in school by Boko Haram insurgents during the Buni Yadi massacre.

Buni Yadi is a small town, about 55 km from Damaturu, the state capital. The proximity to the state capital did not do much to protect the town, as even the state capital was not spared from an attack later that year. The Federal Government College located in the town was ideal for many teenagers, not just in Yobe but around the north. The school had students from places as close as neighbouring Borno state, where Fatima and her family were based, and places as far away as Kaduna from the Northwest.

When the terror group attacked in 2014, during a time they were set on an anti-school rampage, at least 29 boys were killed in what has now been known as the Buni Yadi massacre. Parents from all over the north were bereaved.

Some months before the attack that killed him, Mustapha and his younger brother came back home from the boarding school, unannounced, all the way from Yobe state -some 300 km at least.

There were rumours that the terror group would attack the school, he had said. He did not feel safe and neither did many students who had also been fleeing home. He had also heard that there had been attacks in nearby locations.

The boy was right. Attacks were being recorded in many local government areas in Borno and, increasingly, Yobe. Boko Haram was also famous for its anti-western education beliefs. It made sense that the school was in danger. It was close to places like Buni Gari that had been attacked already. For reasons such as these, many would come to believe the Buni Yadi massacre was avoidable.

At first, people tried to convince Fatima that the boy was making things up, perhaps because he did not like school, or was tired of boarding school, as boarding students were known to do all sorts of things to evade school. Fatima said no, her son was not a liar.

And so she began to explore other options for school for her two boys. She herself worked at a federal government college in Borno and so was aware that private schools were expensive for people like her. Still, she put her head into it because she was searching for safety for her children. She sampled a few schools, and the cheapest fee she was given for registration alone was ₦40,000. This was not inclusive of uniforms, books, and reading materials. She could not afford it for both boys.

She explored another option: since Mustapha was in his final year at the time, she would merely pay for him to register in a nearby private school that was safe, so that he could take his final school leaving examinations and proceed to university if he got good results. But the fee, again, was beyond her. In the end, Mustapha proposed to her to leave him at the FGC in Buni Yadi, hoping that nothing would happen in the last months he had left in school. He asked her to enrol his younger brother at the private school instead as that was something she could afford.

“Mustapha has always been compassionate,” she says. And then she starts to cry. Under her breath, she mutters a prayer to God to still the ache in her heart.

In the end, Fatima took his advice and enrolled Ibrahim in the private school. When the dust around the possibility of an attack in Buni Yadi settled, she sent Mustapha back to FGC Buni Yadi.

In Feb. 2014, just as Mustapha was starting his mock final examinations. As she was closing from work for the day, she heard on the BBC that there had been an attack at the school in Buni Yadi the previous day. Her heart sank.

At the time, there was no network coverage in Monguno, so she could not make any calls to Mustapha’s school guardian to enquire about him. She also wondered why his guardian would not have called her nearly 24 hours after the attack was said to have taken place, especially because she had a good relationship with him and had known him long before he started working at the school.

“He was a staff at the school where I taught before he was transferred to the FGC Buni Yadi,” she says of the teacher.

Fatima trekked to another village in search of network coverage. When she finally found it and attempted to dial her son’s guardian, it would not go through, meaning his phone was either off, or he was also at a place with no network coverage. Downcast, she went back home and asked if anyone had been able to reach Musty’s guardian. They were all already tense and panicky, and no one had been able to reach him.

Later that night, she heard that there was a man who lived nearby and whose daughter was also a student at the school. She contacted him to see if he might have more news than she did. He did not, but he was getting ready to drive down to Buni Yadi the next day. She asked to come with him, and he agreed.

“I did not sleep that entire night,” Fatima says. “I could not wait for the day to break.”

When morning finally arrived, the man stopped by her house and got her. Together, they started to drive down to Buni Yadi.

While on the way, people from home suddenly started to badger her with phone calls and asked her to return. Shortly after she left Monguno they had heard the details of what had happened and that Mustapha had been killed. It was not news they could relay to her over the phone, and they also did not want her to arrive there and see for herself what had happened to Mustapha, while far away from the people who could console her. But Fatima could not figure out the reason for the constant calls. She told them she had no intentions of returning without first reaching the school. She also had anxieties over stopping on that road because six years before, the road had taken her husband’s life. She just wanted to get to her destination as soon as possible.

Then, after everyone else had failed to convince her to return home, Fatima’s older brother called her. He asked where she was exactly, and she told him.

“Then he said wherever I was, I should turn around and start coming right back home.”

There was something about the man’s words and tone that consumed her with a sinking, knowing feeling that whatever it was that had happened in that school in Buni Yadi had taken her son’s life. She stopped on the road, got another cab and returned to Monguno.

At home, her brother confirmed her fears to her: Boko Haram insurgents had stormed the school that Sunday evening and set fire to all the buildings. They positioned themselves at various entry points and shot and killed boys who tried to escape the fire. Others were slaughtered like animals. Mustapha was killed in the attack with a bullet in his belly.

Her brothers would later go to the school on her behalf.

“They found his corpse, dressed him, and buried him,” she says. And here she breaks down for a long time. When she regained her composure, she said in a tone that made it impossible to know if she was speaking to herself or to me, “it was Allah’s will. It was Allah’s will. Whatever Allah has willed to happen, no one can stop it.”

Two weeks after the incident, she assembled what was left of her family and moved to Maiduguri, the Borno state capital.

Later that year, she says, she and other bereaved parents were invited by the authorities in Yobe to the government house and handed a cheque of ₦1 million each as compensation. The first source of annoyance was that her name was initially spelled wrong on the cheque, written as Falmata instead of Fatima.

About two years later, the first lady, Aisha Buhari, gave them each an additional ₦200,000. That was about it in terms of support from the government. She never spent a penny of it.

The money just made her angrier. If she had had access to that amount of money at the time Mustapha fled the school, the boy might still be alive now. She would have been able to withdraw him from the FGC, register him at a safe, private school, and given him an education that was worthy. Of what use was that amount of money after he had been killed? She could not bring herself to spend it.

While families of people who have been victims of the insecurity in Nigeria often admit that no form of support could possibly fill the hole left behind by their loved ones, they say it helps to some degree to know that their pain has been acknowledged, and the death of their family is recognised and felt by the people charged with securing them – the government.

“Nothing can be done to help,” Fatima sobs. “‘It has already happened. But it would help for him to be remembered.”

Ibrahim, who she had successfully withdrawn from the school and enrolled at a privately run school in Maiduguri, tries to console her when he can.

“He told me that the money was not Diyyah and I shouldn’t see it as such, because if it were, it would be a lot higher than that. Diyyah is expensive.”

Diyyah is the Islamic term for the monetary value of the life of a person who was killed, paid to their family by the killer.

Ibrahim is now a third-year student of Zoology at the university.

Mustapha was her first child. If he were alive, he might have been well on his way to becoming the doctor he had always dreamed of becoming.

“But Allah did not will it to be.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter