The Boys Lured into Boko Haram’s Enclave with Food Rations

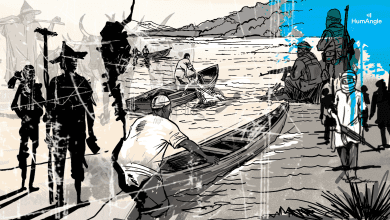

In North-central Nigeria, terrorists are weaponising hunger as a strategy to recruit vulnerable children into their fold. They would ravage specific areas, destroying their crops and farming infrastructures, looting stores and private houses, and then position themselves as the only source of food for children.

Hassan Audu is lost in the past.

Tricked into a Boko Haram camp in Niger State, North-central Nigeria, the 16-year-old is mired in the mud of his traumatic experience as a child soldier. He is a witness to the terror and tragedy devastating his hometown of Shiroro. He struggles to move towards a glimpse of the future. Audu’s nine-year-old brother, Ja’afar Hassan, was caught in Boko Haram’s vicious net in 2022, with families and friends thrown into agony that the terrorists had conscripted their beloved son. For years, no one could trace Ja’afar’s footpaths to the camp; his parents wallowed in pain, begging local authorities in the Mashekeri village of Shiroro to help retrieve their son.

When Ja’afar’s captors sauntered into the village in 2024 for their exploits, they encountered a weary Audu, exhausted from his desperate search for his younger brother. The terrorists took advantage of his desperation, asking him to follow them into the forest to retrieve his brother. He hopped on a motorbike, wedged among the terrorists, as the rider zigzagged his way toward the forest’s edge.

“They asked me to come see my brother. When I arrived, they locked me up in a mud cell,” Audu tells HumAngle. “We used three motorcycles, two people each, including the one I was on. They asked me to come with them and see my brother. Since I knew my brother was with them, I went along.”

The boy wears a sour face and a sober appearance, beaming softness and stone-heartedness simultaneously. One minute, his eyes catch tears during the interview in a secured location in the Hudawa area of Kaduna State in northwestern Nigeria, and the next minute, he carries a terrifying face, stirring up a panic-stricken atmosphere.

Concerned that he might go rogue if allowed to travel alone, Audu’s stepmother, Laraba, accompanied him from Zamfara to Kaduna to speak with HumAngle. Since returning from the terrorist den, his chances of going berserk have been high, according to the stepmother, who noted that the boy has lost his tenderness as a teenager, occasionally displaying wild behaviour and betraying a civil demeanour. Blame him, but also blame the men who lured him into the valley of violence, keeping him in the logistics unit of the camp where he witnessed how terrorists planned attacks, brutally punished offenders, and detained civilians for ransom.

The terrorists fed him enough tuwo, a local Nigerian meal made from maize, and a hastily prepared tomato soup. He had wanted to return home the same night with his brother, but fed like a cat, Audu stayed, with the terrorists promising more sumptuous meals if he swallowed their rulings. He had more than three square meals that he couldn’t have at home. Back in Mashekeri, a single solid meal daily was a luxury. The boy found that luxury in multiple folds in the terrorist camp and stayed glued to it, quickly forgetting his initial mission to bring his brother back home.

“I never missed home. Whenever I mentioned home, they would say, ‘Some other time.’ Since then, the feeling of returning home faded,” Audu tells HumAngle.

He is one among dozens of children lured with food to embrace corrosive doctrine peddled by violent extremists. The food weaponisation strategy is deployed by a fragment of the Boko Haram terror group predominantly settling in the lush canopy of the Alawa Forest in the Shiroro area of Niger State. Caught up in the terrorist zone, children are vulnerable to hunger and displacement and are trained to become brutal terrorists.

They are recruited into different areas of terrorist operations. While Audu, for instance, was placed in the logistics unit, his younger brother was taught how to spot a target and pull the trigger. Teenage girls trapped in the camp are kept as wives, a euphemism for sex slaves. The women are also responsible for the food supply, preparing meals for the captives and commanders in the camp, and determining the food ration formula.

Fed to forget home

The terrorist group deliberately ravages specific areas, destroying crops and farming infrastructures, looting stores and houses, and destroying properties to make life difficult for locals.

After impoverishing and uprooting them from the agrarian areas, the terrorists, having access to the food supply, take advantage of the undernourished children, tricking them into their enclaves with promises of enough food and water. They also use this tactic to gain appeal among marginalised communities, seeking to win the hearts and minds of potential supporters by providing crucial services and distributing meals.

HumAngle’s investigation, spanning months of identifying underage boys and girls tricked into the terrorists’ territory, interviews with their parents, and local sources, including farmers and vigilantes, reveals this strategy. We monitored some radicalised teenagers from the moment they were abducted to when they escaped from the terror camps to reunite with their families. Many of the victims’ parents asked HumAngle to hide the identity of their children for fear of reprisals and stigmatisation. Being a minor, we spoke to Ja’afar through his uncle, but Audu and two other teenagers with the same story spoke to us directly.

Several months after they tricked him into the camp, Ja’afar fell into a toxic love with guns and the deadly triggers they pulled. As a child, he was trained in the art of using a weapon to snuff life out of a human being and to get a human to do his bidding in seconds. When Audu witnessed his younger brother’s newly acquired prowess in spraying bullets, he fell flat for the escapade.

“It was an admiration. I admired the way boys my age wielded weapons,” he says. He had thought only grown-up men like police officers could do so until he saw his mates displaying mastery in it and following terrorists to the battlefield as they fought security agents or rival terror groups. “I gradually got used to their lifestyle. I adapted. It felt good, and I liked it.”

This terrorist empire belongs to a man simply known as Mallam Sadiqu. Sadiqu is a Boko Haram commander and a protégé of Mohammed Yusuf, the founder of the extremist group. An adherent of the catch-them-young maxim, Sadiqu heavily invests in manipulating teens and young people. The empire’s underworld setting, known among terrorists as Markaz (centre), makes it easier for them to plan covert anti-state operations.

Interactive map: Mansir Muhammed/HumAngle

Recruiting children as fighters didn’t start with Mallam Sadiqu’s terror camp — terrorists in West and Central Africa deployed child soldiers in their fights against authorities. A 2021 United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) report revealed that since at least 2016, the region has recorded more than 21,000 children used by non-state armed groups.

“Whether children in West and Central Africa are the direct targets or collateral victims, they are caught up in conflict and face violence and insecurity. The grave violations of their rights perpetrated by parties to the conflicts are unacceptable,” UNICEF says.

The global humanitarian organisation added in a 2022 report that over 8000 children had been recruited by insurgents since 2009, describing Boko Haram as the major recruiter of child soldiers in Nigeria. The sect forcibly recruits children to strengthen its fighting ranks, abducting many of them during raids on villages, schools, and camps.

Boys are often trained as fighters, spies, or to carry ammunition, while girls are frequently subjected to sexual violence, forced marriages, and used as domestic servants. Some of the children are direct descendants of these fighters, with terrorists raising a deadly generation of criminals. Boko Haram is also notorious for using children as suicide bombers, with at least 117 kids, mostly girls, used in covert bombing operations between 2014 and 2017, according to UNICEF.

Interactive map: Mansir Muhammed/HumAngle

Bewildered by the near-perfect coordination of the terrorist enclave, however, Audu’s naivety made him think it was a sovereign territory set up for religious purification and built to fight the secular state. The setting first set him off balance before offering an adrenaline of safety, power, and protection from what he thought was the government’s persecution. There were four rogue commandants, with only one supreme leader: Mallam Sadiqu, a dangerous man with a growing network of followers and foot soldiers.

The terrorist apprentice

In April 2025, HumAngle travelled to several satellite communities in the Shiroro area of Niger State. Apart from battling deeply-rooted insurgents, we found that the communities suffer from apparent government absence, turning the local areas into ungoverned spaces. Many villages and townships lacked good roads, hospitals, and basic schools. The terrorists are taking advantage of the governance gap to brainwash children and teenagers into believing in their ideology. There is also the social welfare appeal.

“When I fell critically ill in the forest, a doctor came in to treat me. I was worried that I might not be able to get adequate treatment in the bush, but I was wrong. I got a treatment far better than what I would have gotten at home,” Audu says. Even now that he’s out of the den, he wonders why he got better medical attention in the camp, saying, “This was one of the attractive points.”

Audu was placed under the watchful eye of Muhammad Kabir, the commander in charge of logistics and operations. Considered a stranger, Audu wasn’t given a gun or taught how to use it. He had only seen his terrorist chaperone servicing guns upon returning from battlefields. Kabir also prepared the fighters for operations, especially when they had fierce face-offs with security agents and local hunters surveilling the forest areas.

Kabir moved from the Sambisa forest to the Allawa wilderness to join Mallam Sadiqu in Shiroro. In September 2021, the Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps (NSCDC), released an internal memo confirming that scores of senior Boko Haram fighters were moving out of the Sambisa Forest to work in cahoots with Sadiqu, who was wielding rocket-propelled grenades and shuffling between Kaduna and Niger states at the time. The NSCDC advised security agents to scale up surveillance in the affected areas, according to the memo obtained by HumAngle. Kabir was among the terrorists the NSCDC was referring to, locals and security sources said, corroborating the internal memo.

Audu would later learn how to reload guns for the militants in the camp. He painstakingly watched his boss service various rifles, including the Russian Avtomat Kalashnikova (AK-47), the Gewehr 3 (G3), and Rocket-Propelled Grenade (RPGs). Kabir also prepared the fighters for war against the military and terrorist rivals. Under the operations unit was the group’s bomb manufacturer; he had produced scores of explosive devices used to waylay unarmed citizens and military men, tearing them apart and killing them instantly during face-offs. Audu referred to him as Baba Adamu.

“Baba Adamu had picked Ja’afar up in the village, luring him into the enclave and training him to operate guns and produce bombs,” Audu notes. “Baba Adamu himself learned bomb making from one man who later died during a gun battle with the military.”

Working with the operations unit, Audu’s duty included joining other child soldiers to work on Mallam Sadiqu’s illegally acquired farm fields. In many Shiroro villages, the group has violently evacuated local farmers, illegally occupying their lands to farm. When they needed more workforce on the farms, they abducted vulnerable civilians, forcing them to farm for them. Audu says he had joined other teenage terrorists to supervise civilians working on the farm. They planted beans, maize, and rice and harvested richly while the local farmers struggled to cultivate their fields over fears of being attacked.

Dozens of farming communities in Shiroro also signed a peace deal with the Sadiqu-led terror camp, paying millions before accessing their farm fields. In 2021, a journalist documented how 65 agrarian communities paid over ₦20 million to access their farm lands and live peacefully in the villages. In the same fashion as terrorists in northwestern Nigeria, Sadiqu partners with communities and, in some cases, collects levies to allow people to farm freely.

“We would travel through villages in the Alawa town to work on Mallam Sadiqu’s fields, which are close to people’s homes. Sometimes, we would spend days on the farms, planting and harvesting. We planted maize and rice most of the time. It was a big field,” Audu adds. “Almost all those who can ride motorcycles in the camp used to labour there. Almost all of us used to go there to work. We used to buy boiled cassava from the townspeople. But when the people fled, we harvested the cassava from the farms. We would boil and eat them while on the farms.”

Shadow justice

One man, Mallam Shaffi, was the spiritual commandant of the gang, usually regarded as the amirul da’wah. He led daily prayers and preached on Fridays, encouraging the children to neglect modern ways for their anti-Western governance path. Every morning, he admonished the combatants to fight for God’s cause, manipulating verses from scripture to convince his disciples that Western ways would only lead them to hell. Anyone antagonistic to their violent operations and extremist tendencies is an enemy and must be taken out of the way, Audu says.

Although Sadiqu presided over the general affairs of the camp, Mallam Shaffi served as the Amirul Khadi (chief judge). This role gave him oversight that ensured discipline and strict adherence to their extremist doctrine within their sphere of control. He was consulted before judgments were made on offenders. In this clime, misdemeanours could attract capital punishments; petty thieves caught with their hands in the cookie jar were first jailed before their hands got cut off.

When Sani, Mallam Shaffi’s younger brother, was found guilty of petty theft, he was not spared. “His hands were cut off instantly; they passed a judgment,” Audu recalls. It was his first time witnessing such a gory scene, wondering why a man would lose his hands “just because he stole”. But something even more shocking unfolded before his eyes months after he arrived at the forest: six combatants were killed on the camp’s wild execution ground.

“They killed them for imposing a tax on the Gbagyi locals and seizing their farm produce,” Audu tells HumAngle. “The fighters executed are Jabir Dogo, Usmna, Attahir, Abdullahi, Elele, and Abu. They killed them about a month ago.”

The black market justice system turns like a vicious circle: if the rules favour you today, they might be used against you tomorrow.

One morning, Ja’afar woke up locked in a cell, with his hands and legs tightly bound. He was accused of stealing petrol and bullets from the logistics store. Ja’afar’s case seemed different from other thefts recorded in the past. While others stole from civilians on the other side, he stole from the terrorists — that was considered a grave offence, raising tension that the punishment might be more than cutting off his hands, like they did for Sani.

Audu’s worry suddenly grew cancerous; he was there to rescue his brother, and now he had been fed so much that he even forgot about going home. The detention of his younger brother tensed his worry; the probability that the young lad would be killed was high. He had committed treason, according to their laws, and the most severe punishment for such an offence was brutal death.

Rumours mounted that Mallam Shaffi had ordered that Ja’afar’s throat should be slit. That rumour flared up Audu’s fear. He had lately been nursing the thoughts of escaping the forests due to increased aerial attacks from the military. That trepidation was aggravated when the military perpetuated surveillance of their camp almost every day, killing the combatants frequently.

“Teenagers far younger than me and my sibling had been killed in that forest, either by the terrorists or the military,” Audu says, enveloped in his sweat. Months after leaving the camp, the boy still lives in fear, displaying paranoia towards every positive event around him and showing violent tendencies at any provocation.

Lost in the lush

As he forged escape routes for himself and his brother, Audu says he thought about scores of girls also trapped in the terrorists’ camp. Girls from satellite communities in Shiroro were tricked into the underworld after they were promised better living conditions. One girl, Zainab Mainasara, suddenly disappeared after terrorists raided her community in 2021, kidnapping a considerable number of girls. Since then, Zainab’s parents have done everything to retrieve their daughter from the hands of the terrorists. Later, they learned she had settled with them, marrying one of them.

When Audu came to the forest, he met Zainab. He had learned about her from the lips of villagers, especially how the terrorists attempted to pay her bride price to her father in the Kurebe area of Shiroro. HumAngle spoke to her father, Ali Mainasara, somewhere on the shore of the town, where he is currently burying his head. He left the Kurebe community in shame after villagers accused him of marrying off his 17-year-old daughter in exchange for farming freedom.

Ali denied the allegation during an interview with HumAngle, saying he wanted to give his daughter the formal education he lacked. “But the terrorists took her away from me one afternoon, with guns and weapons in their hands,” he says, amid sobs. “If she were with me, she would probably have finished schooling or legitimately married.”

Zainab’s mother, Fatima Mainasara, left the community for a neighbouring village. The incident that took their daughter away from them also shattered their homes, as Fatima seemed to have swallowed the flying rumour that Zainab’s father sold her out to terrorists. “Since the incident, her mother has been quite distressed and experiences anxiety daily. She has been diagnosed with chronic hypertension. The reality is that we are suffering deeply. I am urging the government to assist in securing my daughter’s release so that she can be safely reunited with her family,” Mainasara cries out.

Audu knows where to find Zainab, but cannot take anyone there. While in captivity, he realised Zainab was forcefully married to his chaperone in the forest, Muhammad Kabir. Now with two kids from the ‘unholy’ marriage with the terrorists, Audu recalls that Zainab and many other girls were in charge of cooking and sharing food in the camp. Knowing each other from Shiroro, they had met on many occasions and exchanged greetings, but they’d never had a chance to discuss anything. It was forbidden to be seen discussing with the fighters’ wives in the camp.

“Zainab’s first child was named Adam. I don’t know the second boy’s name,” Audu notes. “Adam could be around two or three years old. The boy can walk and talk. The second boy is an infant.”

Mainasara’s worries double up at the mention of his daughter’s sudden disappearance into the woods. He fears Zainab might have been brainwashed into the realm of extremism, as news emerging from the terrorist camp revealed she had been fully immersed in the life outside her home. Her mother, once chubby, has become emaciated due to the anguish of her daughter’s disappearance. The grief has taken a toll on her health, but Zainab’s captors won’t let her go.

Scores of girls in Kurebe are in Zainab’s shoes: they were indoctrinated by terrorists a few years back, and now they can’t look back. One such girl is Rumasau Husaini, who was just 11 years old when she was abducted in 2022. Her father, Haruna Husaini, is still desperately searching for her. He once offered to pay a ransom for his daughter’s release, but it failed.

“When we reached out to the terrorists, we asked them to return her, but they told us it was impossible since she had already been brought into the forest,” Husaini recounts. “They mentioned discussing her dowry, but I refused to entertain that. All I want is my daughter back.”

Other girls caught in the trap of the terrorist group include Mary, Azeemah, and Khadijah — all from the Kurebe village of the Shiroro town. While Zainab was betrothed to Muhammad Kabir, Mary was forced to marry Ismail, another terrorist, and Azeema was given to Mallam Shafii.

As the grip of Boko Haram grew stronger in Shiroro, casting a shadow over the community, girls and boys became an endangered species. Mallam Sadiqu took over the leadership of several ungoverned communities neighbouring the Alawa Forest. One evening in 2021, he announced in his local mosque, with his voice echoing through the modest building: all girls must be married off or risk being forcefully betrothed to terrorists.

“Any female child that is up to 12 years old should be married off,” Sadiqu was quoted to have announced, instilling fear among the parents who listened. Unable to bear the thought of their daughters being taken by terrorists, many families chose to flee, relocating their girls to safer locations or sending them to displacement camps in more garrison areas.

When Sadiqu finally took absolute control of the political and economic lives of the locals, he propagated his extremist beliefs, wielding threats like weapons and eliminating anyone daring to defy him. He banned schools, stripping formal education away from children and forcing them into menial jobs and denying them a brighter future.

The tragedy deepened so much that the Nigerian military declared Kurebe a terrorist zone. In April 2022, six out-of-school girls were sent to fetch water from the nearby Kurebe stream. In a cruel twist of fate, they were mistaken for armed terrorists by the Nigerian military. An air raid ensued, killing the unprotected children who had already been traumatised by the circumstances forced upon them.

As the dust settled, it became clear that Boko Haram’s reign of terror was far from over. With schooling activities ground to a halt in the community, the terrorists began abducting the very children they had denied an education. The girls were taken as brides, and the boys were forcibly recruited into their radical ideologies, whisked away to secret camps hidden deep within the forests of Alawa.

“Up till now, some of our boys and girls are still missing,” laments Yusuf Saidu, the district head of Kurebe. He looked disturbed as he spoke of the lost boys and girls missing from their homes and families. “They marry the girls and sometimes even come to pay dowries to their parents.”

As military surveillance abounded in the Alawa Forest, Mallam Sadiqu built fortresses around himself to dodge attacks. Then, fear grew like wildfire in the terrorist camp, especially among children and teenagers trapped in the camp. Audu realised his younger brother could be killed if he folded his arms — either by military airstrikes or through the terrorists’ shadow justice system, which recently found him guilty of stealing.

One night, while everyone slept, he crept into the cell where Ja’far was caged and untied him. Discreetly, the two brothers walked out of the camp, trudging through the woods to find a way out. After days of sojourning in the forested expanse, they finally reunited with some relatives in the Shiroro area. Knowing they were not safe anywhere in the town, their relatives moved them to a community in northwestern Nigeria.

Back to square one

For Ja’afar, it was a free ride out of the lion’s den. And for Audu, the journey had only just begun. Their lives never remained the same; even after escaping from the radical world, they struggled to adapt to a regimented civilian lifestyle under their guardians. A few months after reuniting with families, Ja’afar exhibited attitudes suggesting he could no longer live in a civilian community. He would threaten his mates with death or charge at them at any slight provocation. His family has handed him over to the military in Kaduna State, hoping for a deradicalisation and psychological reform process so he can be safely reintegrated into society.

Audu, who appears calmer, was moved to Zamfara State to stay with a family member and is under tight monitoring. The family feared the proximity of the original town to Shiroro could later prompt the teens to return to the terrorists. Months after they returned, the boys seemed to be back to square one. Audu, for instance, is not enrolled in a school and struggles to have three square meals as adequately provided to them in the terror camp.

The situation remains dire back in Shiroro: locals caught up in war zones can hardly feed themselves properly, as food insecurity bites harder. Unfortunately, food insecurity is a reality for many Nigerians, yet those in power tend to downplay the issue. The United Nations predicted last year that by 2030, over 80 million Nigerians might face a severe food crisis. In many villages and displacement camps HumAngle visited while gathering this report, hunger, malnutrition, and food insecurity dominate the land, with hundreds of locals uprooted by the insurgency relying on animal feed due to an extreme food shortage.

HumAngle spoke to Dapit Joseph, a child psychologist at the Federal University Kashere, Gombe State, to further understand the implications of children being recruited in this manner.

“You know, food is a physiological need; it’s the foundation of human motivation and the first in the hierarchy of needs. People need food to survive, and in the quest to get it, they can do anything to survive. When people are hungry, especially children, that hunger can be weaponised to lure them into terrorism,” he asserts.

Joseph noted that we can neither blame the children nor the parents in this situation, because “when you’re caught up in a devastating war-torn area, you lose a lot of things, you become traumatised, and all you do is struggle to survive. It’s a very terrible condition that comes with a lot of psychological effects.”

The psychologist thinks the government needs to prioritise rehabilitating and providing social support for the children. Social support, he says, includes providing the basic needs these families require to survive and educating the parents on how to take care of these vulnerable children in society.

“Religious bodies have a role to play. You know, we attach serious meaning to religion in this part of the world,” he advised. “So if religious bodies can go, talk to these people, give them hope, and tell them that it won’t remain like this forever, it would help.”

For a region big on farming and fighting insecurity, it remains unclear what the Niger State authorities are doing to avert Boko Haram’s weaponisation of food shortages to recruit children. However, the permanent secretary of the Ministry of Niger State Homeland Security, Aminu Aliyu, recently told local journalists that the government and security agents were aware of the situation, failing to reveal steps to put the situation under control.

Laraba, Audu’s stepmother, worries about what might happen to him and his younger brother. She says she ponders every day, with no clarity, how to ensure these children do not derail again. Her heart pounds whenever she sets her eyes on Audu every morning because she’s clueless about providing a permanent succour to the brothers.

Audu’s parents are stuck in Shiroro, living from hand to mouth, swept under the control of terrorists in the ungovernable Kurebe village. Now, looking after their children has become a burden for Laraba, who complained recently that Audu has refused to return to school after terrorists brainwashed him against Western education.

“He has now returned to Hudawa, and he shouts about wanting to get married, instead of going back to school, but we’ve warned him against that,” Laraba says. For a 16-year-old, the stepmother thinks marriage should not be the next chapter in Audu’s life, but the boy seems convinced otherwise.

Audu’s return to the town also bothers Laraba because the area, although in Kaduna, borders Shiroro, making it easy for the boy to return to terrorism if he finds no help. “We’re seeking help from all angles so that he can at least start a business even if he can’t return to school,” she says.

Ja’afar’s uncle has also expressed doubt over his fate. He says living with the military has not yielded desired results, noting that the boy does not seem to have been deradicalised months after he was taken to the army. As it stands, the future of both boys has been halted.

Asked if he was considering going back to the forest fringe if he gets the chance, Audu says he would not hesitate if another chance was given, “because I got enough food that I don’t have access to even at home.”

Hassan Audu, a 16-year-old from Nigeria, experienced a tragic ordeal after being tricked into a Boko Haram camp while searching for his kidnapped brother, Ja’afar. Captured and manipulated by the terrorists, their strategy of using food and false promises lured numerous children into their ranks, indoctrinating them with extremist ideologies. These children are often trained as fighters or subjected to domestic servitude, with Audu himself ending up in the logistics unit. The terrorists exploit conditions of food insecurity, leveraging these hardships to further entrench their influence over vulnerable communities.

The situation in Shiroro and other affected areas is dire, with basic infrastructure, education, and necessities like food being scarce. Children like Audu struggle to reintegrate into society after escaping such environments, highlighting flaws in efforts to deradicalize and support them adequately. Additionally, Boko Haram's integration of Sharia-inspired control within their camps, involving brutal punishments, creates an atmosphere of fear and obedience, making it difficult for captives to escape.

While Ja’afar is undergoing military deradicalization attempts, Audu’s struggle continues as he grapples with societal reintegration and the lack of adequate food and educational resources.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter