The Almajiri Girl’s Long Distance Race To Relevance

About three in 10 almajiri children in Nigeria are girls, but the world has hardly paid attention to how the controversial system of Islamic education affects them.

In 2012, when she was only seven, Maymunah* left her home in Dandinshe, a small community in Kofar Ruwa, Kano State, for Makafin Dala. The only reason her parents gave her was her paternal grandmother’s blindness. Her mission, they instructed, was to assist the old woman in begging for alms.

Also known as the ‘Colony of the Blind’, Makafin Dala’s reputation as a haven for the visually impaired is steeped in myth. According to one account, the town emerged because of a blinding curse placed on some Maguzawa, a Hausa subgroup, for their refusal to accept Islam. Another theory suggests it was founded by a blind warrior, Kassassawa, giving rise to the influx of other blind people.

Today, Makafin Dala is home to hundreds of visually impaired people, who because of their disability resort to begging for their daily bread. They rely on young almajiri girls like Maymunah to support them and also attract the interest of passers-by.

Maymunah does not get paid for her services but is given new clothes during Muslim festivals, allowances for food, and drugs whenever she takes ill.

She admits she regularly faces discrimination, insults, and harassment from older residents because of her work as a beggar’s guide.

“I feel bad,” the 15-year-old says. “Most times, I feel like returning home. If I am able to stop begging for alms, in shaa Allah, I will be very happy.”

Fortunately, she attends both a tsangaya (Islamic learning centre) and a public secondary school, where she is currently in JSS 3. In the morning, she goes out with her grandmother to solicit charity from open-handed strangers and, by late afternoon, she would hurry off to school. Eventually, she hopes to study Medicine and Surgery in order to “help those who are sick”.

But in spite of her tall ambition, she would rather settle down as a housewife than continue schooling because of a lack of resources.

“If I further my education, I will have to take care of myself,” she says. “But, with marriage, the man will take care of my needs.”

Unlike Maymunah and other girls in Makafin Dala, many almajiri girls do not have the opportunity of getting formal education.

The girls mostly live in rented apartments in the town, “so dilapidated you could even see what is happening there from outside,” joked Aliyu Dahiru, a resident of the Local Government Area. The work of helping disabled beggars was male-dominated about two decades ago. Today, it is estimated that only one out of 10 of the children is male.

“Those giving the alms are only attracted to the girls. If you want to give money because of sympathy, there are beggars without guides you can help,” Dahiru observes. “Sometimes, the girls will look fine. They bleach their skin. You won’t even think they are guides when they are not with the beggars. They dress up well.”

“And sometimes even when they are begging, they would really be flirting with you,” he adds as he twists his face and winks amorously to illustrate what he has seen.

Who is the almajira?

Though Mohammed Sabo Keana has run the Almajiri Child Rights Initiative (ACRI), an advocacy organisation, for over four years, he still finds the concept of female almajiri baffling and “unthinkable”. At first, he hoped it was not true there were girls who participated in the system. He, however, soon realised there was no escaping that reality.

“There are female almajiris,” Keana concedes. He has either seen or received reports about them in Kaduna, Sokoto, and Zamfara states.

Almajiranci is a system practised mostly by the Hausi, Fulani, Nupe, and Kanuri tribes of Northern Nigeria where young children are sent to Islamic schools, oftentimes in distant places. Many of these children, however, resort to begging in communities in order to sustain themselves and pay their teachers.

While the male child is known locally as almajiri, almajira refers to his female counterpart.

About 10 million children are estimated to be directly affected by this practice, constituting over 80 per cent of Nigeria’s out-of-school population, and the poster boys for the system are often thatㅡboys. But then, in a 2009 study, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) estimated that as many as 30 per cent of the almajiris in Kano and Zamfara were female.

“Almajiri schools are usually male only schools,” Deepika Chawla, Senior Associate at Creative Associates International which implemented the study, said at the time. “In fact, when we got the results, the immediate reaction was that it was impossible. There were ‘no’ girls in the almajiri system.”

Keana highlights the challenges faced by the male almajiris to include physical abuse, sexual exploitation, ritual killing, forced labour, and child begging. Unlike their male counterparts though, it is not common to find female almajiris residing within the school.

“They are almajiris, but outside the school. They go to the school to study and go out for begging as well. Most of them are not boarding students,” says Zainab Yunusa, a community advocate and humanitarian social worker in Sokoto.

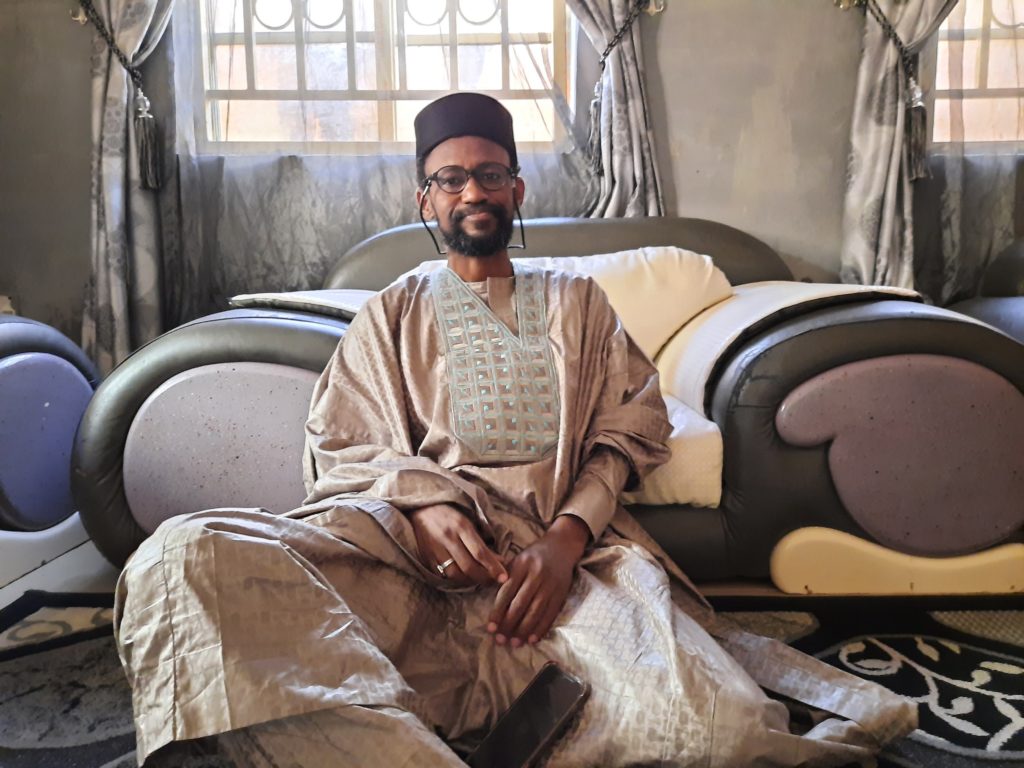

Sayyadi Bashir Usman Bauchi, a Bauchi-based Islamic scholar, explains that his female students are of two types: day students who attend the almajiri school and girls who live with the mallam and are treated as family while they memorise the Qur’an. He himself grew up relating with both male and female almajiris, who were part of the household, as a child.

Bashir is one of the prominent sons of Sheikh Dahiru Usman Bauchi, a leading Tijaniyya scholar whose foundation runs an almajiri school with about 300 branches and 60,000 students distributed across the Northern region. But his school, which employs and houses teachers, is one of the advanced ones. There are almajiri schools in rural areas where students learn in considerably worse conditions.

Based on her visits to various schools in Mabera, Yabo Local Government Area, Yunusa estimates that 20 to 25 per cent of all almajiris in the state could be girls. Many of the girls are from other communities, states, or even other countries in West Africa. While some migrated with one or both their parents, others came alone and stayed with caregivers. In the morning, they go for their Qur’anic classes and later in the day, they move through the streets, begging for alms.

Meanwhile, almajiranci as it is popularly practised violates provisions of the Child’s Right Act, a federal law enacted in 2003 that guarantees every child the “right to parental care and protection” and freedom from exploitative labour. It also provides that no child shall be used “for the purpose of begging for alms, guiding beggars, prostitution, domestic or sexual labour or for any unlawful or immoral purpose”.

Eleven states, all in the northeast and northwest regions, have, however, yet to domesticate the Act 17 years after it was passed.

Sexual violence

Part of what Makafin Dala is notorious for is that it serves as a hotspot for transactional sex with the young female almajiris though the vast majority of them are underage. The girls also often face sexual harassment from residents during the course of begging. This could range from indecent comments to inappropriate contacts.

Maymunah says even though she interacts with other guides, the girls hardly disclose information about abuse suffered. “Everyone keeps it to themself,” she adds.

But a vigilante officer in Makafin Dala who spoke to HumAngle says his team receives at least two cases of sexual harassment on a weekly basis, which they hand over to the police.

Yunusa narrates the experience of Zahrah*, a young almajiri from Niger Republic who settled in Sokoto with her parents, after they had moved from one place to the other. Both parents begged until the father secured a job as a security guard. Later, Zahrah met a rich, elderly ‘alhaji’ who raped her. Rather than face justice, he covered up the incident by offering to marry her. Her parents agreed. Zahrah was only 13 years old at the time.

She suffered harassment as the Alhaji’s wife. Months into the marriage, one of his older wives poured hot water on her, scalding a great part of her upper body. Alhaji simply returned Zahrah to her mother, who still tried persuading her to go back.

“There is harassment. There is child marriage and child labour. Anything you can think of, those children are facing it,” Yunusa says. “In most cases, if anything happens like sexual harassment, they will cover it up. If you take them to the station, they will disgrace you there because they would have bribed the police officers.”

Shrouded in secrecy

Keana says getting access to female almajiris who are still enrolled has been tough for his organisation because of the wall of suspicion erected by their mallams (teachers). In Bauchi State, this reporter and his fixer faced similar difficulty as they spent days trying to get access to female almajiri students without success. Their teachers, about five of them, were not comfortable with the idea.

When one finally agreed to arrange an interview with his female students, too much emphasis was perhaps placed on the word “arrange”.

Each time the girls were asked to describe how much they have learnt in years of attending the school, the answers seemed terse: Hadith, Qur’an, Islamic Jurisprudence, Islamic History, and with the Mallam’s prompting they added English and Mathematics.

Rather than allow the girls to reply freely to certain questions, the mallam, Naziru Shu’aibu, jumps in to puncture their silence. “She wants to further her education,” he says when Hannatu, 17, was asked what her post-graduation plans were.

What higher school of learning does she have in mind? “Anyone,” she says. “Don’t you want to become a doctor?” her teacher asks unprovoked. “Yes, I want to become a doctor,” she replies in a frail voice.

But among the schools in the community, which one does she like? The fixer himself answers on her behalf: “They normally do Higher Islam, it is like secondary school, then they go for NCE. After NCE, they go for a degree programme.” Which school? “Fa’il Khaer Academy,” the mallam says. “Among the colleges of education, we have Tatar, Ibn Abbas, COA Azare, and Legal School, Misau.”

Okay, but why does she want to become a doctor? “I want to help the female gender,” the mallam whispers and Hannatu, raising her voice, echoes his statement exactly.

When this reporter asks Firdausi, a 15-year-old classmate of Hannatu, what she wants to do upon graduation, the fixer immediately suggests, in translating, that she should say she wishes to “further her education”.

Minutes later, she says she would like to get married. “If I marry and I get permission from my husband, I will further my education,” she clarifies.

When 11-year-old Halima is called forward and asked if she wants to attend a Higher Islamic School when she is done at the almajiri centre, the fixer does not bother translating the question. “Um-um, yes. They are planning the same thing,” he says guardedly.

To abolish or not?

While Sayyadi Bashir agrees there are challenges with the educational system that need addressing, he says the solutions must come from within. Meeting with this reporter in one of his houses in Bauchi, he does not hold back his distrust for western civilisations, which he says promote immorality and the pursuit of pleasure.

“There is no society that does not have problems, but why should our problems be a source of attack?” he asks.

“We need to be very wary when we seek solutions. They can’t tell us what to do. They can’t tell us what is good for us and what is not good for us. There might be female almajiris, but that does not invalidate the entire system.”

He blames the proliferation of almajiri beggars on widespread poverty and the lack of support from well-to-do citizens. Indeed, Nigeria’s northern states, according to a World Bank estimate, have 87 per cent of all poor people in Nigeria. Yunusa considers poverty a major factor as well but Keana does not agree.

“When we met some of the parents in the villages and asked if the problem was that they could not feed their children, they replied ‘haba! We have enough,’” he recounts.

He has learnt from his many interactions with the parents of almajiri children that they are happy to enroll their kids in school. The problem, he says, is that those schools are just not within reach in those communities. The least they think they can do to secure their children’s future is therefore to get them Qur’anic education in almajiri schools.

This argument was echoed by former Kaduna State governor, AbdulKadir Balarabe Musa, who argued in May that the almajiri system would end if the government instituted free and compulsory basic education.

While Yunusa does not think the almajiri system should be scrapped, she strongly opposes the involvement of girls.

“For the females, it should be totally banned because even the ones who are not almajiris are facing issues of rape. I don’t think it is advisable. There should be nothing like girl-child almajiri because of its consequences,” she proposes.

“And if at all there should be, there are also female scholars. They should not be under male instructors; they should not be going out for street begging. Just like girl boarding schools, they can be kept in a place where they have total freedom to move around, under a female scholar.”

Kolawole Olatosimi, national coordinator of Child and Youth Protection Foundation (CYPF), an Abuja-based NGO, also takes the middle ground and emphasises the need to strike a balance. Criticising the almajiri system is not the same as passing negative comments on the religion, he says, and while educating a child opens them to multiple choices, “religious beliefs are not sufficient to empower them for a better future”.

Kolawole urged the various northern states to have a sincere dialogue about the Child’s Right Act (CRA) with the aim of domesticating it without threatening established customs.

“Child’s rights cannot wait. The more we linger to pass the CRA in these 11 states, the more vulnerable we are making children,” he says.

“If a child from the south moves to the north and anything happens, there is no law that protects that child. You can be from Kaduna State that has passed the Act under a different name and move to Kano; the law does not protect you. Children in Nigeria should be able to move to any part of the country and be adequately protected.”

Blending with western education?

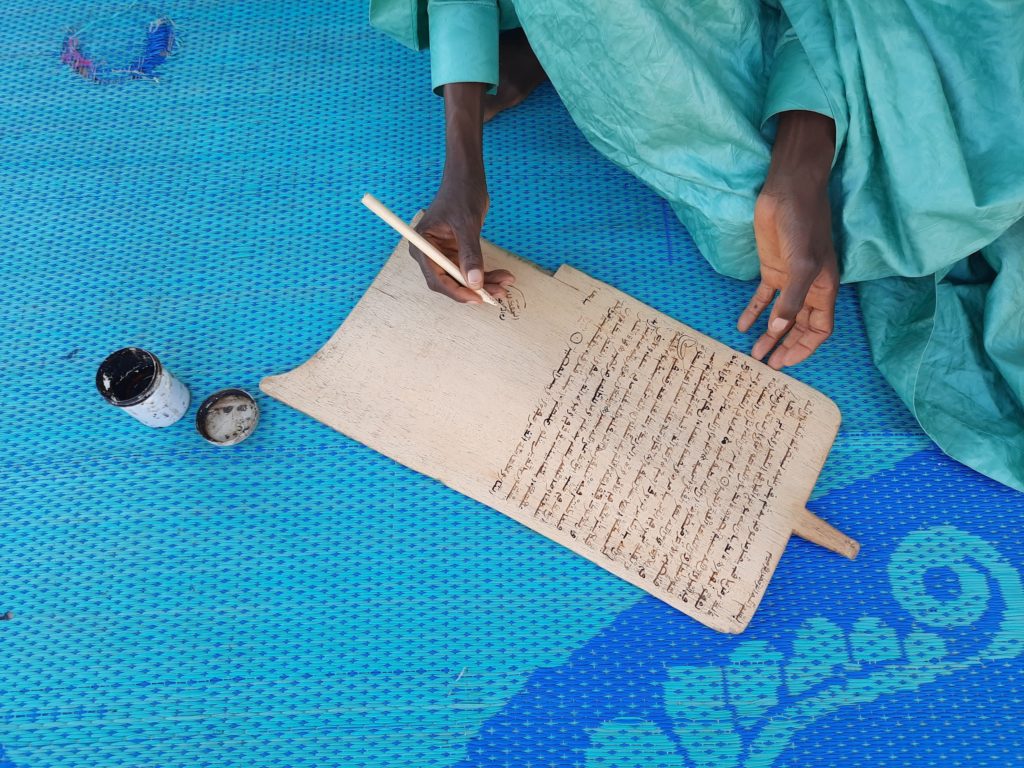

At the Sheikh Dahiru Memorial Islamic School and many other almajiri schools, students are taught Islamic jurisprudence, Arabic grammar, Arabic lexicography, and are guided to memorise the Qur’an. In the precolonial era, graduates of such schools could easily be employed as imams or into the civil service in various capacities. But that is no longer the case with the evolution of the education system, leading to a rethink about the relevance of the old almajiri practice.

About 10 years ago, the Sheikh Dahiru school started experimenting with a combination of Islamic and secular classes. After it obtained a licence from the state ministry of education, its programme of four years was extended to six years to accommodate additional English Language and Mathematics lectures. Students are then conferred with the equivalent of a primary school leaving certificate.

“We made some experiments with a few schools and succeeded, so we are trying to expand the programme across the branches,” says Sayyadi Bashir.

But is it really succeeding?

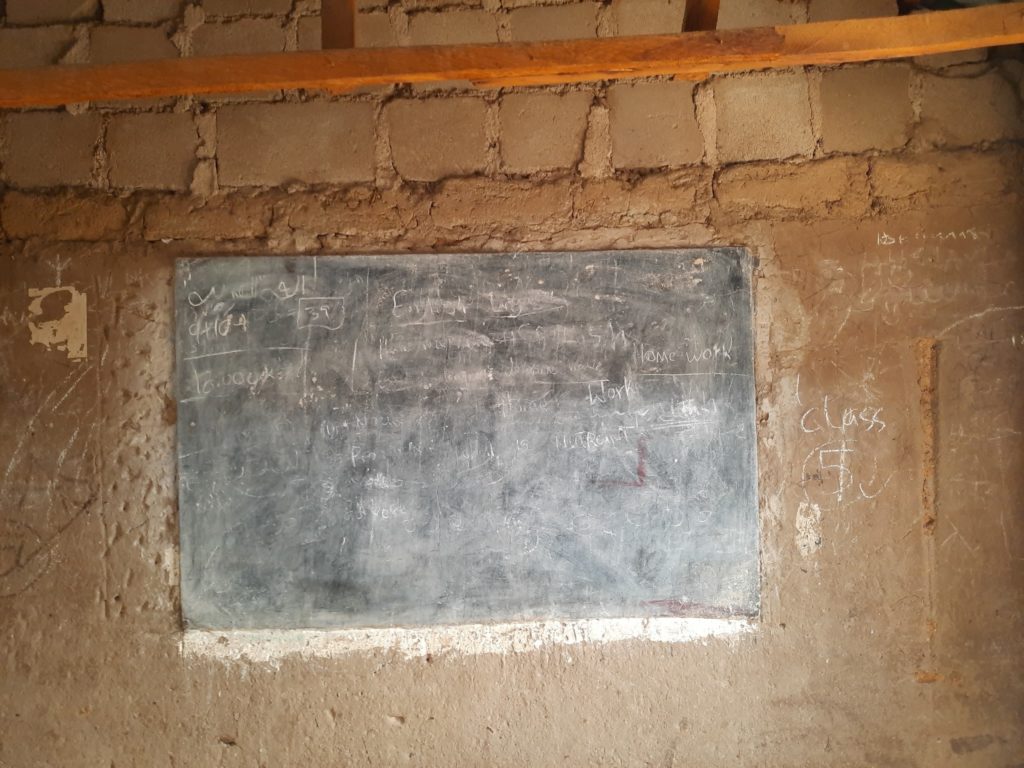

When HumAngle finally got access to some female students of the school in Bauchi, they did not seem to be able to speak any English despite being in advanced classes. Two of the girls interviewed were in the final, fifth class but the interview questions had to be translated to Hausa before they could understand and reply.

How good is Hannatu’s English? “Very little,” the mallam says in Hausa addressing the young girl. “Very little,” Hannatu repeatsㅡalso in Hausa.

The students are not given English textbooks. They all rely on the blackboard and texts consulted by the mallam. Also, they are only taught the western education module for two hours, twice in a week: Thursdays and Fridays. From conversations with the mallam too, it was obvious he spoke very little English.

The student’s grasp of the Qur’an likewise did not seem impressive.

Though Halima says she wants to return to the school to teach Qur’an, she has difficulty mentioning her favourite chapter. “Suratu-l-Yasin?” her mallam asks. “Waqi’a? Maryam?” Finally, she recites a line famously repeated about 90 times in the scripture: Ya ayyuhal ladheena aamanu (O you who believe). “She means Surah At-Tahrim,” the mallam comes to the rescue.

Yunusa, the Sokoto-based community advocate, believes it is not often the thirst for knowledge that pushes children into almajiranci, but rather pangs of hunger. This, she explains, is because many of them, in fact, do not make significant progress in learning.

“Most of these almajiri we are talking about cannot even read Suratu-l-Fatiha [the first chapter and one of the shortest in the Muslim scripture]. Tell me, a child who has been into almajirinci for about five years or so and is not able to read Fatiha, what is that child doing in the school?”

Keana encourages combining religious studies with western education, but warns that it should not be restricted to literacy and numeracy. What they are learning has to be multidimensional, equitable, and non-discriminatoryㅡ“It is not for anyone to say they are almajiri and should just be given Maths and English.”

He insists their educational pattern must be measurable and inclusive such that they can compete with students in other institutions.

“How do they become doctors just by learning English and Maths? That is also deepening the inequality gap we are talking about. The concept of equality means level-playing ground for everyone,” he stresses. “There is no alternative to the fact that they must have Qur’anic and western education, and they are not mutually exclusive; they can go together.”

The ACRI boss’ position is supported by the 2004 Universal Basic Education Act which enjoins parents to ensure their children complete their primary and junior secondary school education. “School,” the Act warns in its later pages, “does not include a class for religious instruction.”

Though the Sheikh Dahiru school boasts that one of the employment opportunities open to its graduates is teaching positions at its branches, Mallam Shu’aibu admits there are currently no female teachers where he works.

“Most of them marry after graduation at the age of 17, 18,” he explains reluctantly.

Nigeria’s impenetrable govt. walls

This paper tried, but without success, to get comments from relevant federal ministries about ongoing programmes for the almajiri and, specifically, plans for girl child education.

During a phone call, an assistant to the Director of Press and Public Relations at the Ministry of Education directed the reporter to visit the press unit for a response. Access was, however, not granted to the director, Ben Bem Goong, who was either said to be busy or to have stepped out.

Though the Deputy Director was on seat, he also declined granting an interviewㅡfirst because he was busy and then for various other reasons including that he did not know this journalist.

“If you are one of our correspondents or your office has written letter here that you are going to be covering this place, we will start seeing you. We will start knowing you. We don’t just grant interviews to anybody because they mention they are a journalist. I don’t talk to people anyhow,” he explained.

Halimah Oyelade, spokesperson for the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs, Disaster Management, and Social Development, promised to connect the reporter with relevant programme officers after discussing with them. But this did not happen despite subsequent calls and text messages.

When we visited the Ministry of Youth, a top official at the press unit explained that, because of government procedures, the paper would have to submit a proposal requesting for comments and then get approval from the Permanent Secretary. But how long will this process take? “Not less than a month,” the official replied casually.

Shehu Makai, the Director of Press and Information at the Ministry of Women Affairs, which is also in charge of child development, did not answer calls placed to his line nor has he replied texts sent on seperate days. He was not at his office when the reporter visited too. An assistant director at the ministry, during a phone conversation, said he could not grant an interview unless a letter was written and he received permission.

Similar challenges were faced with state governments.

Makut Simon Macham, Director of Press to Plateau State Governor who is also Chairman of the Northern Governors Forum, did not respond to texts or return calls on different days. The forum comprises all 19 states in the northern region and deliberates on issues that are common to them.

Likewise, for four days, between November 17 and 20, the phone number of Muhammed Bello, Special Adviser on Media and Publicity to the Governor of Sokoto, was called and texted without acknowledgement.

Flicker of hope

State governments in the North appear to agree there are byproducts of the almajiri system that must be addressed and have adopted different approaches to do this. They also insist there are no female almajiris within their communities in the same sense as we have male almajiris.

“It is not in our culture to take female children away from their parents and relatives to another place. Completely, it is not acceptable,” says Zailani Bappa, Special Adviser to the Zamfara State Governor on Public Enlightenment and Media.

He adds that the government is making efforts to enroll the children in school. However, rather than integrate secular courses into almajiri curriculum, the administration believes in treating both systems “with their own dignity”.

“We want to give the system an uplift instead of just modernising or changing its pattern. The state government is trying to ensure that it builds schools for all the tsangayas where the children will be domiciled instead of having them move from one place to another,” he explains.

“The government intends to give them support to improve the situation so that the children learning the Qur’an will have more conducive places to sleep, sit and learn, and less urge to go out and beg for food. This is what the state government has been trying to do and we shall continue to do it.”

Also speaking to HumAngle, Salihu Tanko Yakasai, Special Adviser on Media to the Kano State Governor, says one major step the government has taken is to declare basic education up till secondary school level as free and compulsory.

“By implication, girls are expected to be going to school. Even if they are going to be married, by virtue of that law, they have to continue going to school,” he says.

The government provides free uniforms at the primary school level and has extended the Federal Government’s school-feeding programme to include children in primary four to six. Yakasai says the government is also deliberate about improving infrastructure to accommodate more students. For instance, about 16 new girls-only Junior Secondary Schools are under construction.

The state commissioner for education, Muhammad Sanusi-Kiru, had announced in January that over 500,000 out-of-school children had been enrolled as a result of the government’s policies.

Yakasai further assures that the state has gone far towards domesticating the Child’s Right Act though under a new name “for obvious reasons”. The government is trying to ensure all stakeholders key into the new law as some have expressed concerns about some of its provisions.

“It has gone far in the state assembly. It is at the final stage; I think it is almost done. I asked a couple of months back and that was the update. I assure you it is going to be passed,” he says about the bill which was introduced to the state assembly in 2019.

Though progress may be slow, there has recently been a consensus among state governors in the northern region about the need to take action. The governors of Kano and Kaduna have at different times assured that all members of the Northern Governors Forum are on the path to reforming the almajiri practice. The forum members reaffirmed this commitment at a meeting held last September.

In the meantime, experts continue to warn that Nigeria will not make significant progress unless it addresses the almajiri issue and harnesses every child’s potentials. “Why the system has gone on this far, for me, lies squarely on the irresponsibility of the leadership and government,” emphasises ACRI team lead, Keana.

“For whatever guise, there is no justification to make children be on the streets begging in the manner we see them. And like I told you, it is almost unbelievable for me that there are little girls at the mercy of the community. It is vulnerability at the highest order.”

*Pseudonyms are used to protect the girls’ identities.

This report was supported by Media Monitoring Africa as part of the 2020 Isu Elihle Awards for child-centred journalism.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter