The Alarming Rise of Femicide in Cameroon

Ekobena’s situation is similar to that lived by many other children and family members whose fathers or brothers killed their spouses. It also shows the ripple effects of such heinous crimes on those left behind.

Christina Ekobena* has lived in Douala in Francophone Cameroon for five years. She was forced to relocate outside her native Kumba in Anglophone Cameroon after her father brutally beat her mother to death. In the wake of the attack, enraged neighbours destroyed her family’s home in protest, and her father was sent to prison.

With nowhere left to turn, she had no choice but to leave.

“I feel like I am living in another planet because I am far away from my origins and my own family and friends,” Ekobena told HumAngle. She struggles with stigma, the demands of school, and adapting to an unfamiliar environment.

“The sudden and brutal change in my life makes me feel like I am paying for a crime I did not commit,” she said in tears. “But what do I do? I don’t have a home to return to. My other siblings are living with family members who were kind enough to accept them. Some family members and friends refused to take us because they were afraid we might have killer instincts like our father and kill their children or themselves.”

Ekobena’s experience reflects the reality of many children and family members whose fathers or brothers have killed their wives or partners. It also highlights the ripple effects of such heinous crimes on those left behind.

The term femicide, once rarely used and unfamiliar to most Cameroonians, is now becoming part of everyday vocabulary due to the increasing number of women killed by their husbands or boyfriends.

One case that drew national attention occurred on July 25, 2020, when Franck Derlin Oyono Ebanga, a 30-year-old civil administrator and sub-divisional officer for Lokoundje in Cameroon’s South region, shot and killed his ex-girlfriend, Lydienne Solange Taba, a student at the University of Douala. The brutal crime dominated headlines for years as legal proceedings unfolded at the Ebolowa Military Tribunal. On March 6, 2024, Ebanga was found guilty and sentenced to ten years in prison. He was also ordered to pay a fine of 45 million FCFA (approximately $71,983).

Before this highly publicised case, gender-based violence committed by men against their women partners was often dismissed as an unfortunate but accepted norm within Cameroonian families and relationships. The silent killings were so normalised that even government institutions—tasked with protecting women’s lives—failed to keep records of such crimes. Cultural norms and fear of stigma further prevent many women from reporting gender-based violence or seeking care, according to a report by Afrobarometer, a pan-African research network.

Violence against women in Cameroon has become not only more common but also more brutal. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, rising femicide cases were linked to increasing militarisation, entrenched gender inequalities, and economic hardship. In just three months, between May and July 2020, numerous media reports documented women killed by intimate partners, security forces, and insurgents in the ongoing Anglophone conflict.

About 67 femicides were reported across the country between Jan. and Nov. 2024. While this figure appears alarming compared to previous years, it barely scratches the surface. Many believe the actual number could be more than double, as many cases go unreported or are misclassified.

Notable cases of femicide in Cameroon

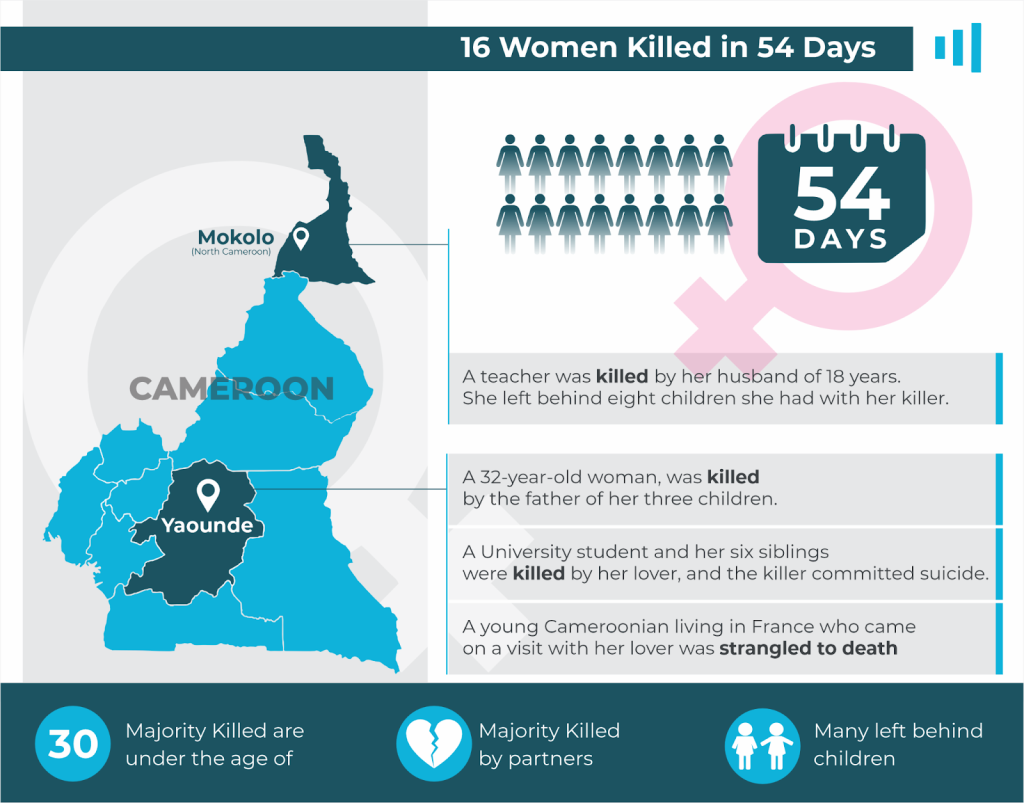

Within 54 days in 2023, 16 women were killed in Cameroon, most of whom were below thirty years old. Some of the cases are:

- On April 12, 2023, in the town of Mokolo in North Cameroon, a teacher was killed by her husband of 18 years, leaving behind eight children.

- Vanessa, a 32-year-old woman of three, was killed in Yaoundé by Jean-Charles Biyo’o Ella, her children’s father.

- Dorace, a University of Yaoundé student, and her six siblings were murdered by her lover. Before authorities could apprehend him, the 32-year-old man took his own life.

- A young Cameroonian woman living in France, visiting Yaounde with her lover, was strangled to death in a hotel room.

Nearly 89,000 women and girls were intentionally killed worldwide in 2022, according to UN Women and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Of these, approximately 56%, or about 50,000, were killed by intimate partners or other family members.

However, it’s challenging to determine the number of femicides in Cameroon accurately; this is due to the absence of a centralised database for homicide records. The country’s law enforcement system is fragmented, with the National Police handling crimes in urban areas and the Gendarmerie overseeing rural regions.

Hence, there are no clear structures for reporting, and in some cases, both institutions document the same incidents, further distorting the data.

A system that fails women

Cameroon’s Constitution guarantees women the right to life, physical integrity, and humane treatment. It explicitly states that “no person shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.” Yet, in practice, these protections remain largely theoretical.

Violence is deeply embedded in Cameroonian society, manifesting as state violence, insurgent attacks, terrorism, civilian-on-civilian brutality, and domestic abuse. Within this culture of violence, women remain particularly vulnerable.

Journalist and women’s rights activist Tricia Oben said, “Femicide in Cameroon has been rising at an alarming rate over the past two to three years, and the government’s weak, almost indifferent response has only fueled the crisis. Women are being slaughtered—there’s no softer way to put it—and yet, the authorities continue to treat these murders as isolated incidents rather than as a systemic emergency.

“And yet, beyond a few routine condemnations, where is the actual action? Where are the tough laws, the fast-tracked investigations, the severe sentences? Nowhere. Why? Because the patriachal system still fundamentally sees women as expendable.”

Oben believes the rise in femicide is closely tied to shifting gender dynamics:

“For decades up to the early nineties, women in Cameroon were treated as accessories; there to serve, bear children, and disappear into the background. Now, that’s changing. Women are rising in business, politics, and education. They are earning their own money, refusing to stay in abusive marriages, and demanding a say in their futures. This shift has shaken the traditional power dynamics to the core.

“Many men, unable to handle a world where women are no longer submissive, are lashing out in the most violent way possible. Femicide is not just a crime; it is an act of desperation by those who feel their control slipping away.”

Stronger systems are needed, Oben noted, with real laws that hold perpetrators accountable.

The fear factor

The brutality of recent femicide cases further exposes the deeply ingrained culture of gender-based violence. Victims like Larissa Azenta, Lizette, and Comfort Tumassang were not just killed—they were mutilated. One was burned, another decapitated, and another had her head severed entirely.

Corinne Aurélie Moussi, an expert in international law and gender-based violence, argues that these violent acts serve a sinister purpose.

“The viciousness accompanying these murders manufactures female fear. By waking up to news of women being slaughtered by intimate partners or other men, Cameroonian women are reminded that their lives are not their own. They are subtly, indirectly warned that in a relationship, there is no escape, except through violence or death.

“This fear factory operates because it relies on the privilege of the aggressor and the vulnerability of the victim. The perpetrator knows he can act with impunity. He is aware that the system protects him, not his victim.”

Moussi insists that victims must not be reduced to statistics.

“Women who have suffered and continue to suffer deserve justice. Those who have lost their lives at the hands of their partners should be remembered, not just as numbers but as human beings whose lives mattered. It is imperative to stop trivialising women’s issues.

“We must be relentless in dismantling the patriarchal system that enables this violence. And we must hold aggressors accountable, because no man should feel entitled to a woman’s body or her life.”

No ‘type of woman’ is safe

Is there a specific profile of women who are more vulnerable to femicide? The Cameroon Association for the Fight Against Violence on Women says no.

“The victims are not killed because of their age, ethnic group or their socio-economic situation. They are most times killed by their partners or former partners just because they are women and vulnerable.”

The association has called for the establishment of a dedicated service to provide psychological and legal support for the families of femicide victims. It has also secured the services of a lawyer and a jurist to help families navigate the judicial process, free of charge.

Yet, the slow and bureaucratic nature of Cameroon’s legal system means that many femicide cases drag on indefinitely, ensnared in administrative bottlenecks.

Professor Claude Abé, a sociologist at the Catholic University of Central Africa in Yaoundé, believes the fight against femicide must begin at home and in schools. He calls for nationwide sensitisation campaigns to educate citizens about the dangers of gender-based violence and for civil society organisations to play a more active role. He also advocates for stronger legislation to protect women and girls.

Eric Kombey, a public health specialist and community development expert in Yaoundé, echoes this call for urgent action.

“Femicide has become a pressing societal issue, with a disturbing increase in brutal murders, intimate partner violence, and ritual killings. This crisis demands immediate intervention from the government, civil society, and all stakeholders.

“Strengthening legal frameworks is critical. Laws against gender-based violence must be strictly enforced, with no room for impunity. Harsher penalties must be imposed to serve as a deterrent.

“But beyond legal measures, we must expand support systems for at-risk women. Psychological and legal assistance, economic empowerment programmes, and safe shelters for survivors are crucial. Community awareness campaigns are also essential to challenging harmful societal norms and fostering a culture of respect.”

‘Who will accept us back?’

For survivors like Christina Ekobena, the trauma of femicide lingers long after the headlines fade. Returning to her former community is not an option—not only because she has no home but because of the stigma that follows her.

“Nobody would accept us back,” she said. “They fear we would be a bad influence on their children if we were allowed back in school.”

Yet, with growing awareness of the crisis and increasing pressure on the government to act, experts remain hopeful that Cameroon will finally take meaningful steps to combat femicide.

Christina Ekobena, forced to flee her home in Anglophone Cameroon due to her father's crime, represents many affected by femicide's family disruptions. Femicide, rising in Cameroon, notably impacts women killed by partners amid gender violence norms. Notable cases include a high-profile shooting in 2020 and multiple murders in 2023. This violence, exacerbated by weak legal responses and societal indifference, urgently calls for systemic reform.

Cameroon's legal system inadequately protects women, with entrenched gender violence dating back decades persisting. Activists and experts emphasize stronger laws, awareness campaigns, and support services.

Victims are often left without justice and face societal stigma. Initiatives to combat femicide include psychological and legal support, but progress is hindered by slow bureaucratic systems.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter