Surviving Hell (6): From A Harrowing Detention Cell To An Unfamiliar Home

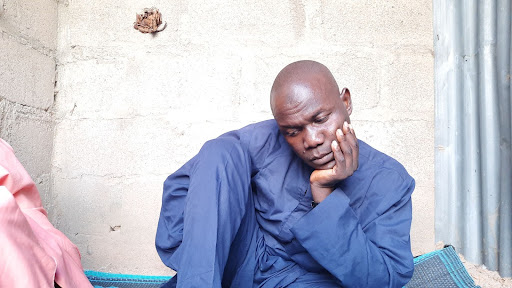

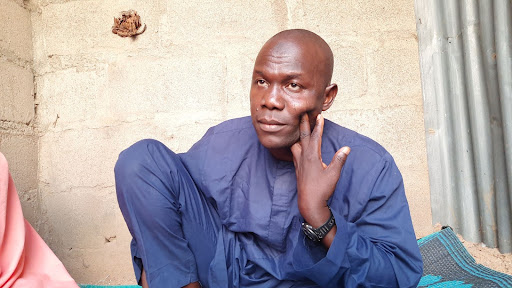

Baana Alhaji Ali left his village in Borno State after Boko Haram terrorists took over. He fled to Cameroon but was handed over to the Nigerian Army and labelled a terrorist. After six years in prison, he has regained his freedom.

While Baana Alhaji Ali was in detention, the officials at Giwa barracks where he was held would move from cell to cell every morning to ask if there were any dead bodies to evacuate; people who had died overnight. There was always one; “an average of four to five bodies daily.”

But one day in Baana’s cell, there were no dead bodies.

There was, however, a terribly sick man. When the men came with the expected question that morning, the inmates answered, “No, there are no dead bodies, but there is a very sick man.”

The officials responded that they were only there for the dead. “They said they only wanted corpses,” Baana says. This happened frequently. They would ask that their attention be drawn only after the person had died, he said.

There was no help available to sick people.

Before Boko Haram, Giwa barracks, and dead bodies, Baana was a trader who sold sacks in his village, Andara, in Borno state, northeastern Nigeria. He had two wives and six children. His home housed members of his extended family, including his brothers and their own families. The siblings owned farms and had labourers who worked on them. A truck used to fetch firewood for their wives to cook with and there were boys who fetched water and filled up containers in the house to ease household chores.

Then, the insurgency came and life as he knew it ended.

“We used to stay peacefully but they [Boko Haram] came and took over our village. They refused to let us go out of the village; they imposed their laws on us; they said we shouldn’t allow our women to fetch water, gather firewood, and that we should be doing all that for them. They took foodstuff away from us.”

Finally, Baana and his companions decided that they could not continue to live in a town governed by terrorists and plotted their escape to towns they considered safer. This was in the early months of 2016.

“We got the opportunity to sneak out when soldiers attacked Kumshe,” he says.

Even though they left in the middle of the night, they were still accosted by the terrorists. “When we ran into them, they fired guns at us and we dispersed and ran into the bush to hide.” When things appeared to have settled, they continued their journey.

They ended up in Cameroon.

The Cameroonian army, however, turned them in to the Nigerian army, and it was then that their woes began. “We first went to Cameroon and from there, their soldiers took us back to Banki in Borno State.” It was one of the towns that the Nigerian army had registered a strong presence in at the time, but which residents would shortly begin to flee due to the prevalence of the terror attacks.

They spent a day in Banki and then were taken to Bama. After four days in Bama, the women and children were filtered out and transported to a displacement camp in Maiduguri, while he and other youths were then taken to Giwa barracks, he remembers. Among these youths were himself, his brothers, and about 35 other people. His aged father was also among them. Sadly, he died in Bama before they left. Though they did not know it at the time and would not know it for a long time, they were being detained on suspicion of being Boko Haram terrorists. The Nigerian army had in that year and the year before been carrying out mass arrests of IDPs in this fashion, in their counterinsurgency efforts following the spike in Boko Haram attacks. Many of them, innocent, would after several years be cleared and released, with no compensation.

Baana insists that he and the 39 other men he had been travelling with were neither terrorists nor had ever had anything to do with Boko Haram.

He talks about the hardship at the barracks, but the most recurring part of his narration is thirst. “We didn’t get enough water … some people died of thirst,” he says during one part of the narration. “Water was really scarce, they used to give us pure water only sometimes,” he says in another part. “We really suffered from thirst,” he stressed again moments later.

There were nearly 400 people in the cell. “People died from the heat … We didn’t have proper toilets at first, just plastic buckets to urinate and pass stool. People would take them out when they were full, and empty them,” he says.

The military detention facility has been known for all these and worse.

One day, after three months, his name and those of about 700 other people were called out. They were then handcuffed in pairs, and transferred to the Borno Maximum Security Prison where they spent the following five years.

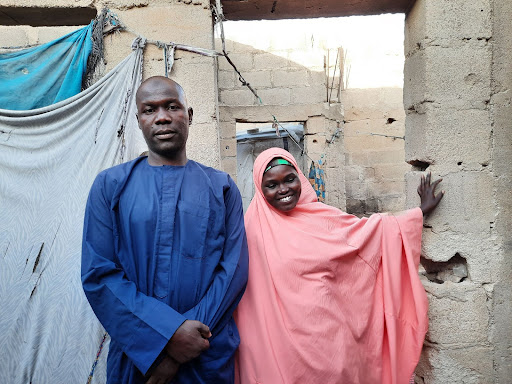

During this time, his wife, Yakura Kumshe, and many other wives of similarly detained men, formed a movement that would later be known as Knifar. Through it, they advocated for the release of their men. Yakura told HumAngle that at the time they started the advocacy, they were unsure that their efforts would yield anything.

“We did not have any hopes when we started. Because this sort of thing has never happened before. We have never seen it and we have never heard about it. We are the first set of people to ever experience it. If it had happened before, it would have enabled us to measure and predict outcomes, like ‘so-so’s husband was detained, but he was released after so-so time.’ But we were the first. So, we just kept advocating everywhere, taking our cries everywhere, and praying,” she said.

Baana’s detention

Throughout Baana’s six years in detention, he was able to correspond with his family a total of five times, through letters. It was a strenuous affair.

“It was difficult finding someone to write the letter, and then finding someone to deliver it to our families. I would tell them [in the letter] that I was doing fine and they would respond praying for our release.”

His time at the maximum-security prison was agonising but productive. The living conditions were also better than his experience at Giwa barracks. “They gave us food three times daily, and we also got water to drink and bathe. They let us out from 9:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. daily. There was adult education too but no vocational training. We were also able to make local caps and sell them.”

He would knit the caps and then hand them over to some of the prison warders who helped him to market and sell them. They always got their money back, except they usually had to hide it. “When we get the money, we have to hide it, because if the prison officials see it, they would seize it… We sold each cap for about ₦8,000.”

Those who didn’t sell caps sold provisions in the prison instead. “Like pasta, cooking oil, and the rest,” he says.

Throughout his stay, he says, there were never any talks of court. He also never had access to a lawyer. “But there was one time some people came and asked us to tell them the truth about ourselves.” The information, when they offered it, didn’t seem useful, as those people never returned.

He notes that another batch of 600 people was brought into the prison after his batch.

Release

Finally, after a total of six years, he was released. “There were people who were transferred to Gombe [Operation Safe Corridor camp], there were people who were released, and there were people they said would be prosecuted,” he explained.

When Baana returned home, he found that home was now an IDP camp. He found that seven of his family members had died in his absence, including his father, brothers, cousins, and an aunt.

He also discovered that his wife had been advocating tirelessly for his release.

“I felt very happy about it,” he says.

His biggest dilemma, like hundreds of the just-released people, is a source of livelihood. He wishes to go back to his business of selling sacks, but is unable to because of lack of capital. He hopes that the government will help provide capital for him; he believes that he is entitled to some kind of justice and compensation.

So far, he has only been offered ₦10,000 at the point of his release. This, he used to transport himself back home from the prison. He came home with nothing, and to nothing, except family. “That is something, at least,” his wife says.

This report is produced in partnership with the Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD).

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter