The journey of a typical Boko Haram/ISWAP member often begins with recruitment, which may be voluntary or coerced.

Once enlisted, the individuals serve either as fighters or in non-combatant roles. Life in the forest encampments where these groups operate varies, shifting between periods of relative stability to episodes of intense chaos. Over time, many eventually leave the group due to unfavourable conditions or a change in personal conviction. Those who surrender typically go through the Operation Safe Corridor programme, a code name for Nigeria’s official rehabilitation process for terrorists who surrender. Over 50,000 people have reportedly surrendered to Nigerian authorities through it.

Abubakar Adam’s story, unlike many others, is different. He voluntarily joined Boko Haram in Borno State, northeastern Nigeria, in 2014, a period when the group was at the height of violent operations seeking to establish what it believed to be an Islamic State.

When his hometown, Bama, was recaptured by the Nigerian military from the control of Boko Haram, Abubakar, alongside other members, fled to Banki, a border town between Nigeria and Cameroon. According to Abubakar, the border town was already occupied by Boko Haram at the time, and so life was simple for him.

“When we arrived at Banki, we were offered a good reception,” he recounted. “They took us in, providing us with food and shelter.”

At first, Abubakar was sceptical about his decision to join the extremist group. For days, he wrestled with doubts, wondering whether life as a terrorist was worth the choice he had made. Eventually, survival instincts outweighed his hesitation. “I had no choice but to join them fully, as we were desperate for survival. That’s how I became a Boko Haram member.”

Banki became the place where Abubakar embraced his identity as a member of the group. He took part in several fierce battles with the Nigerian military and other pockets of violent operations in the area.

“As a Boko Haram member, my life was boring and unfulfilling,” he said. “We spent most of our days in the forest, moving from one location to another and engaging in farming activities to sustain ourselves. However, I never struggled financially, as the group provided us with basic necessities and some financial support.”

Occasionally, Abubakar found himself reflecting on the cause he was part of, especially as each day brought uncertainties, violence, and the constant threat of death. “I knew that our actions were causing harm to innocent people and that our ideology was flawed. I began to question the legitimacy of our cause and the true intentions of our leaders.”

Life for Abubakar became a relentless cycle of evading aerial and land assaults by the state military, searching for sustenance, and grappling with food crises that plagued their isolated group. Eventually, he joined a smaller faction of about 400 people, including women and children, who travelled in vehicles armed for protection. They relocated to a remote area in Cameroon, where Abubakar’s primary responsibility was overseeing their makeshift settlement, which consisted of huts and farmlands.

Describing what life looked like, he said, “I worked as a farmer during our stay in Cameroon, buying and selling farm produce. We had a large population of over 400 people, including women and children. We established Islamic schools for our children.”

Abubakar added, “I never participated in war operations, as my role was to oversee our base when others went out on missions…We had spies who informed us of potential attacks, allowing us to take necessary precautions. Our base was well-organised, with a clear hierarchy and division of labour. We had a system of governance, with leaders who made decisions on our behalf.”

Despite occasional feelings of guilt, Abubakar admitted there were moments he appreciated, such as the sense of camaraderie and shared purpose within the group.

Returning to Bama

His life, however, took a sudden turn in late 2020 during an ordinary trip to a local market in Banki to trade farm produce. While wandering through the stalls, a radio broadcast caught his attention. It was the voice of Babagana Zulum, the governor of Borno State, urging Boko Haram members to surrender and abandon their radical ideology.

“This was the first time I heard it officially, and it hit me hard,” Abubakar said. “In the forest, they never let us listen to such things. It was like a veil lifted, and I started questioning everything.”

The decision to leave, however, was fraught with danger. Escape under the watchful eyes of a tightly controlled environment was nearly impossible. It was risky, as failure could cost him his life. Abubakar told HumAngle that people who had been caught attempting to escape were brutally executed or served severe punishment.

After countless sleepless nights, a simple yet daring idea came to him. “I pretended I was going to the market,” he explained. “I acted as if it was just another routine trip, but this time, I never returned. I made my way back to Bama.”

The journey was dangerous for so many reasons. Every step felt like a gamble, but the thought of freedom and the chance to rebuild his life gave him the courage to push forward. Using a commercial vehicle, as any local traveller might, Abubakar paid his fare and travelled from a remote village in Cameroon to Bama, a town in northeastern Nigeria.

When he arrived in his hometown in 2021, he was struck by how much the town had changed. Once a place ravaged by conflict, it had transformed into a bustling town with military personnel carrying rifles, people everywhere, and resurrected buildings.

“I did not know where to go,” Abubakar said.

As he wandered, he was shocked to recognise familiar faces—people he had once encountered in the forest, some of whom had been involved in terrorist activities. Despite the overwhelming changes, he headed to his old neighbourhood, where his home had once stood. His family, friends, and neighbours had not known his fate after he fled Bama. At the time of his departure, many assumed that those who disappeared were either killed or lost forever.

A day after his arrival, Abubakar had an unexpected reunion with Sawayi*, an old acquaintance he had known at Banki, the border town where his journey into Boko Haram had begun. Sawayi warmly welcomed him and offered to show him around the town and introduce him to lively places. He even advised Abubakar on how to blend into the society.

Unlike Abubakar, Sawayi was reintegrated into society through an official rehabilitation program. He attended the Hajj Camp rehabilitation centre in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno State. As Sawayi took him around the town, he told him about the reintegration programme.

“I didn’t go through the Hajj Camp rehabilitation program, as I had heard mixed reviews about its effectiveness,” Abubakar said. “After the first week of my stay, I met several surrendered Boko Haram members, and we used to live together in the forest. I consulted with those who had surrendered and gained insight into the rehabilitation program.”

As he settled into Bama, Abubakar found himself appreciating the freedom to start afresh. “I decided to present myself as someone returning from a trip. I dressed well and acted as though I had been away on personal business. Since people in Bama didn’t know I was a Boko Haram member, reintegration was straightforward,” he said.

Eventually, Abubakar married a former Boko Haram member he had met earlier during their stay in the forest. They have two children and are building a life together in Bama. “They are the centre of my universe,” he said of his family.

He works as a carpenter, a trade he learnt from his new friends after his return. His modest income helps him feed his family, but he is ambitious and determined to achieve more. “I need support from the government to start a business, and I’m considering returning to Cameroon to establish a business there,” he said.

Reflecting on his situation, Abubakar acknowledged the disadvantages faced by those like him who bypassed the official rehabilitation programme. “Unlike those who went through the Hajj Camp program, we don’t have training, empowerment, and support,” he noted. “I am interested in the training provided at the Hajj Camp, but I’ve been advised against attending due to concerns and personal fear.”

Abubakar admitted that making ends meet since his return has been a challenge. “I haven’t received any support from the government or individuals since my return. I’ve had to rely on my skills as a carpenter to earn a living, but it’s been tough to find consistent work.”

Still, there are aspects of his situation that he sees as a blessing. “Since there’s been no public declaration that I was part of Boko Haram, my past remains unknown in the community,” he said. “Unlike those who went through the Hajj Camp programme, I don’t face the same stigma.”.

“I regret not having had the opportunity to attend school, which led to my involvement with Boko Haram,” he added.

Ahmad Salkida, HumAngle’s Founder and Editor-in-Chief, as well as a security expert with extensive experience in the Lake Chad region, said the reasons for leaving the insurgency vary significantly and are shaped by personal circumstances, survival strategies, and organisational dynamics within the insurgent groups.

“There are many reasons behind Boko Haram defections,” he noted. “For many, it is hunger and starvation as governments in the Lake Chad region continue to mount pressure and blockade of the region. For others, the constant leadership feuds and gaps between the Boko Haram and ISWAP fighters made their continued stay in the forest to fight a pointless exercise.”

Contrary to broad perceptions, Salkida noted that their defections are not always voluntary or ideological. “There are hundreds of Boko Haram fighters who rebelled against ISWAP and, after losing arms and ammunition to fight back, decided to surrender to the Nigerian, Cameroonian, and Nigerien militaries. To them, ISWAP and the Nigerian state are both Kufr, and the Nigerian military is a less brutal Kufr than ISWAP because of the option of prison rather than ISWAP execution,” Salkida said.

The Arabic term Kufr, meaning being an infidel or disbelief, is often used by Boko Haram and ISWAP in their ideological rivalry to delegitimise each other. This term serves as both an accusation and a justification for proscribing individuals or groups deemed as unfaithful to their version of Islamic ideology or teachings.

The Disarmament, Demobilisation, Rehabilitation, and Reintegration Borno Model (DDRR) is a transformative counter-terrorism project to rehabilitate and reintegrate surrendered Boko Haram members back into society. This framework provides a structured pathway for former combatants and associates to transition from a life of violence and extremism to one of productivity and social acceptance.

The Borno model addresses these individuals’ immediate and long-term needs, including psychological counselling, vocational training, and education. It also emphasises community involvement. By addressing the root causes of extremism and providing economic opportunities, the DDRR program—when done right—reduces the risk of recidivism and contributes to the overall stability and development of the region.

However, concerns have arisen regarding a growing number of former Boko Haram members bypassing the official rehabilitation and directly reintegrating into local communities. Locals interviewed by HumAngle noted that these individuals often exhibit strange behaviours, such as recidivism, resistance to authority, and sudden emotional outbursts, raising the alarm about the implications for social harmony and security.

‘Haunted by many things’

Unlike Abubakar’s relatively seamless reintegration, HumAngle spoke with others who shared disturbing revelations.

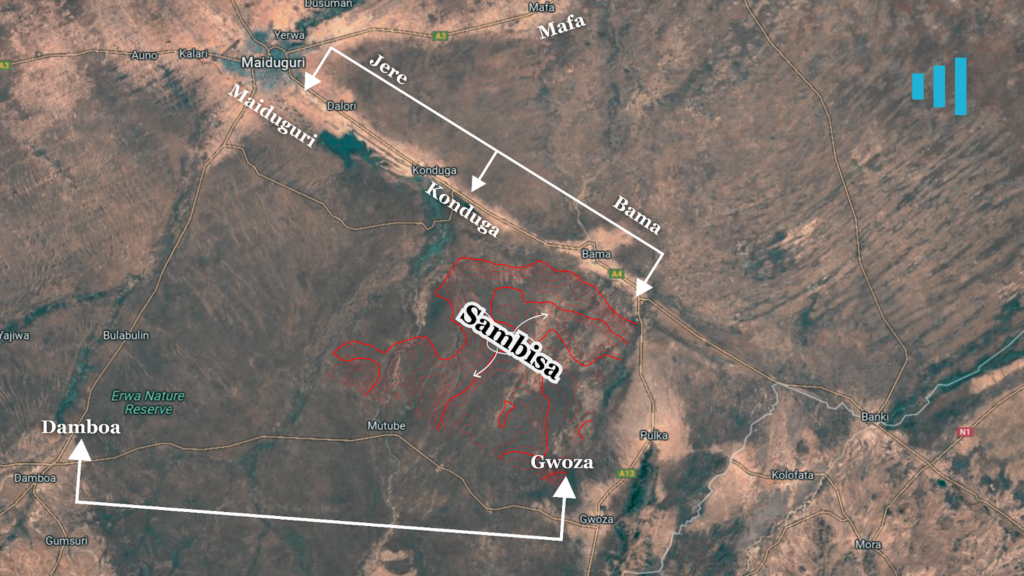

One such is that of Falmata Abba, a 24-year-old woman who Boko Haram forcibly took during an attack on her village in Konduga eight years ago. She was transported to the Sambisa Forest, where, as a captive and young woman, she was forcibly married to a man. Over the years, they had four children while living in the sprawling forest.

“Despite the circumstances, my life in Sambisa was more comfortable than my current life,” Falmata said. “I worked as a tailor and could afford my basic needs. I didn’t have financial problems.”

Falmata and others managed to leave the forest two years ago during a daring attack by the Nigerian Army on their makeshift settlement.

“While several of us ran away during the attack, others were rescued by the military and brought back to their villages. Alongside others, we escaped and returned to our village close to Bama,” she recalled.

Since she returned, she has been haunted by many things, including poverty, discrimination, and stigma. “If I had the chance to return to Sambisa, I would. I am not happy with my life here,” Falmata told HumAngle.

Like many others, she did not pass through any form of rehabilitation, and it has affected her psychologically and socially. “My dream now is to return to my normal life, just like I had in Sambisa,” she added “I didn’t stay in the Hajj Camp rehabilitation program, so I haven’t received any support from the government.”

Falmata said that living with her four children is tough, and she still believes going back to meet other members of Boko Haram in the forest will give her the life she aspires to with her children.

“The support I need is a sewing machine,” she noted. “I don’t need anything from the government. Just a sewing machine would help me regain my life and livelihood. Although I would appreciate training like the kind offered at Hajj Camp rehabilitation centre, I don’t want to stay in the camp.” She learned about the DDRR Borno Model rehabilitation programme from her friends who went through it.

Falmata is painfully aware of how tough life is for someone who had once taken part in atrocities against her own people, particularly given her active role in logistics operations and teaching radical ideology to young people and recruits.

“Since returning, I have faced multiple harassment from community members. For that reason, I have isolated myself, staying mostly at home and avoiding contact with people,” she said.

As the days pass, Falmata counts down to what she believes is her only option: returning to the forest. Isolated and ostracised, she and her children remain on the fringes of their community.

No going back to Sambisa

Aisha Mohammed’s story shares echoes of Falmata’s, but with its own harrowing details.

Aisha, now 30, was captured by Boko Haram insurgents during a brutal attack at Bama, where she was born and raised, a decade ago. At just 20 years old, she was forced into captivity in the harsh wilderness of Sambisa Forest.

“Life in Sambisa was far from enjoyable,” Aisha said. Survival was a daily battle, made worse by attacks from military and rival groups. “There was never a moment of peace,” she told HumAngle. “We were constantly under attack, forced to flee into the forest and return only when the attackers left. I had no family there, no one to turn to for support.”

Amid the desperation, Aisha adapted to her grim reality, though not by choice. She was forcibly married to a fellow captive who later became an active member of Boko Haram. Over time, her husband rose to become a commander in the group. Together, they had children, forging a bond under the most challenging conditions.

“He was a captive like me before joining the group. He is my husband even now,” Aisha said.

After nearly a decade in captivity, Aisha’s chance for freedom came unexpectedly. The Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) launched an operation that created a window of opportunity for her and others to escape. Aisha and her husband ran separate ways when the attack happened. “We were routed to the town by the CJTF personnel that attacked our makeshift camp somewhere in Sambisa. We followed them back to Bama,” she said.

She returned directly to Bama and began the difficult process of rebuilding her life from scratch.

Life outside Sambisa, while better, has not been without its challenges. To make ends meet, Aisha took up sewing local caps, a small business providing her a modest income.

Although far from her reach, Aisha dreams of acquiring new skills, mainly through vocational training programs. “I’ve heard they provide training in various skills. That would greatly enhance my employability and economic prospects,” she said, regretting why she was not able to pass through the rehabilitation process.

Her ultimate goal is to secure a paying job, whether in the public or private sector, to ensure a stable future for her family.

For her, going back to Sambisa is not a choice to consider. “Even if given the chance, I wouldn’t go back. My life there was miserable, and I have no desire to relive that nightmare. I only missed the power we enjoyed because of my husband’s status as a commander,” she said.

Her focus now is on creating a safe and supportive environment for her children, a life far removed from the fear and chaos of her past.

Fortunately, Aisha’s reintegration into society has been smooth. A few years after her return, she was reunited with her family. Her husband, who also renounced his past and returned, lives peacefully with her.

“I’m grateful for the love and support we share,” she said. “I’m hopeful that with the right support and training, I can achieve my dreams and become a productive member of society.”

Failing health

While many former Boko Haram members surrender due to ideological disillusionment, rivalry, or promises of reintegration, others like Rukayya* are driven by a health crisis.

Rukayya voluntarily joined Boko Haram in 2008, during the early days of its formation under its pioneer leader, Mohammed Yusuf. At the time, the group had not yet been declared a terrorist group. However, as conflict between the group and the government escalated, the situation became increasingly unstable, forcing members to retreat into remote areas such as the Sambisa Forest.

Rukayya and her husband lived in the forest for several years, but their lives took a devastating turn when her husband fell gravely ill. Despite the availability of some medical supplies and even a doctor within the group, his condition worsened. The illness became relentless, and no treatment seemed to work. It was during one of her husband’s final days that the doctor revealed the horrible news to her: he had contracted HIV.

“I didn’t know how it happened,” Rukayya said. The diagnosis shattered her, and she became consumed with fear—not only for her husband but also for herself and their children. After months of battling the illness, her husband succumbed to the disease, leaving her to care for their family in the unforgiving environment of the forest.

Soon after, Rukayya began experiencing similar symptoms. The fear that she might have contracted the illness consumed her. When the doctor confirmed that she, too, was HIV positive, her emotions were mixed.

Determined to protect her children, Rukayya took every possible precaution to avoid infecting them. She strictly adhered to the antiretroviral therapy provided by the group’s doctor. Initially, the medication allowed her to maintain a semblance of health, but access to the drugs became increasingly scarce over time.

“I knew I couldn’t survive in the forest without the medicine,” she recounted. “It was a matter of life and death.”

Rukayya made the life-altering decision to leave Sambisa. Under the guise of carrying out a routine task, she gathered her children and quietly left the forest in the night after several attempts. Navigating the perilous terrain, with the help of an old woman, she made her way to Bama, where she sought safety and medical attention.

However, Rukkaya found it impossible to stay in Bama for long. The pervasive stigma surrounding HIV weighed heavily on her, making it difficult to receive the treatment she desperately needed. “HIV stigmatisation is deeply entrenched here,” she explained. “People attach so much shame to those living with it.”

She left for Maiduguri, where she found a sense of relief she hadn’t felt in years. The local hospital provided her with a consistent supply of antiretroviral drugs at less cost, stabilising her health.

However, Rukkaya is deeply connected with the life she abandoned in the forest and the people she left who are still taking the course of the Boko Haram ideology. “I missed so many things,” she said. “There is no child discipline here; we have it more when we are there in Sambisa.”

The rehabilitated and the bypassers

To understand the differences between individuals who passed the rehabilitation process and those who bypassed it to rejoin the community, HumAngle interacted with a few who participated in the DDRR programme at the Hajj Camp rehabilitation centre in Maiduguri.

Salkida, commenting on reported cases of recidivism amongst surrendered individuals, warned that it perpetuates a cycle of instability in a region striving to rebuild society and foster social cohesion. “Those that are totally helpless have surrendered to the authorities; hence, the reason why many of them return to the forest once they find a safe place to operate in the forest without the threat of annihilation by rival factions,” he noted.

Speaking on the effectiveness of the deradicalisation programme, he said, “One will expect a robust and holistic deradicalisation and counter-narrative strategy embedded in the Operation Safe Corridor programme led by Nigeria’s intelligence and faith-based assets. However, the programme is fraught with empty promises, a lack of funding, and mismanagement.”

He added, “It is without a well-thought-out liberal doctrinal curriculum, and as such, many that have passed through the program either return to terrorism, end up aggrieved, or relate these frustrations to other prospective defectors to resort to other means if they can.”

Repentance through the voice on the radio

Rawa Ali, a 35-year-old former Boko Haram member, surrendered to the Nigerian Army in 2022. He lived with his wife and two children in the town of Konduga.

According to Rawa, he joined the terrorist group by mistake. “I joined Boko Haram when we were displaced in Bama and had to flee for shelter due to a battle between Boko Haram and the Nigerian Army in Bama.”

When Boko Haram seized the community, they allowed locals to co-exist with them, even if they were not affiliated with the radical group. There was a peace accord between Boko Haram members and locals living in the same place until the Nigerian Army launched an attack to recapture all besieged villages and towns.

The fierce battle between the Army and Boko Haram displaced everyone in Rawa’s hometown, Bama. Rawa fled into the wilderness and eventually settled in Adamawa.

After a couple of years in Adamawa, roaming from one place to another in search of better living, he decided to return to Bama. However, his homecoming was cut short. According to Rawa, his prolonged absence, even after the military had recaptured the town, led to him being declared wanted. News reached him that the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) was searching for him, accusing him of being a Boko Haram member. Fearing what would happen to him if he went to Bama, he was forced to cut short his journey at Nguro Soye.

“We were stranded in the forest with nowhere to go, fearing for our lives. At that time, we had not yet joined Boko Haram. We were simply displaced persons trying to survive,” Rawa said. It was then that a member of the terror group approached him, he said.“A Boko Haram member approached us, saying that since our people would kill us if we returned to Bama, we should join them to promote Islam and serve Allah. He promised us protection, food, and a sense of belonging. That’s how I joined Boko Haram and followed them to Sambisa Forest, their stronghold.

“During my time with Boko Haram, I witnessed many atrocities, but I also saw how they provided for their members. They gave us food, shelter, and a sense of purpose. I was trained in combat and became a member of their operation team. I also worked as a carpenter, utilising my skills to support the group,” he explained.

After a few years with Boko Haram, Rawa began questioning their way of life. His resolve to leave the group solidified after hearing a message from Borno State Governor Babagana Zulum.

“I decided to leave Boko Haram when I heard the governor’s lecture on the radio urging us to repent. He promised to forgive us, stating that violence was not the solution and that we needed to stop and repent. He also promised to provide us with the means to earn a livelihood, including vocational training, startup capital, and reintegration support,” Rawa recalled.

One night in 2021, Rawa and eight others assembled to embark on a dangerous journey to a new life. “We escaped at 2 a.m., careful to avoid detection by Boko Haram sentries. We reached Bama in the morning, where we surrendered to the soldiers,” he said.

After Rawa and his fellows surrendered to the Army in Bama, they were taken to the Hajj Camp rehabilitation centre in Maiduguri the following day. “We stayed at the Hajj camp for ten months, during which time we were enrolled in a programme that provided us with a monthly salary of ₦10,000. Our families also received food items, and after completing our training, we were given ₦100,000 as startup capital to support our reintegration into society.”

However, Rawa made a chilling revelation. “I must admit that I enjoyed my life in the forest as a Boko Haram member more than I do now as a civilian,” he said. “We had a sense of purpose, and our basic needs were met. In contrast, as a civilian living in this community, I struggle to make ends meet. The government’s promises of support remain unfulfilled, and I regret my surrender.”

Despite his struggles, Rawa praised the community’s tolerance. “Despite this, my relationship with the people in my community is peaceful, and I appreciate their kindness. They have forgiven us for our past actions, and I am grateful for their understanding,” he added.

‘We are gradually adapting’

Like Rawa and many others, 32-year-old Abdulrahman Banna also reached a turning point when he heard the message on the radio from Governor Zulum, calling on them to surrender.

He joined Boko Haram at age 25, leaving behind a life of uncertainty for one of rigid control and conflict. Stationed in the village of Jimia, near Bama, he served as a carpenter and an operations team member, delivering goods and assisting in logistical tasks for Boko Haram.

Unlike many terrorists, Abdulrahman never lived in Sambisa Forest but instead experienced a different side of the group’s operations in smaller, mobile bases.

He married and started a family in the forest while with the group. Abdulrahman noted that his basic needs were met, and he even managed to secure financial stability, a contrast to the life he would later encounter after surrendering.

After listening to the radio programme, he confided in trusted traders from town who confirmed the governor’s promises. He then escaped with some of his friends’ wives. Abdulrahman’s decision to leave was not easy. “Had the leaders known about my plans, they would have killed me,” he told HumAngle.

His journey to freedom ended in Bama, where he surrendered to soldiers at Science Bama, a displacement hub for thousands of families. From there, he was taken to the Hajj Camp rehabilitation centre, where he spent eight months before reintegrating into society.

While Abdulrahman acknowledges the moral weight of his past actions, he admitted, like many other repentant terrorists who spoke to HumAngle, that life in the forest, despite its dangers, felt more stable than his current reality, which is plagued by economic hardship.

But he said he has adapted to life in the community, earning the goodwill of many, though he understands that some harbour resentment. “We wronged people, and they have every reason to be angry. But slowly, we are rebuilding trust,” he said.

According to Abdulrahman, he encountered people in market areas and public squares who he had offended in the past or even participated in killing and destroying their properties.

“My relationship with the people in the community is relatively good, but I understand that some may harbour resentment towards me due to my past actions. Because of us, some people lost their relatives, jobs, capital, and shelter. I acknowledge that we wronged people, and we did so without their consent,” he said. “Some will even look me in the eye and tell me all derogatory things because of what I did to them. They curse me and do a lot of despicable things to me. However, we are gradually adapting and becoming a part of the community again, and people are slowly forgiving us.”

Abdulrahman aspires to become a well-established carpenter, secure government contracts, and create jobs for others. “I want to prove that people like me can change, that we can rebuild and contribute positively to society,” he said.

For him, government support is critical, not just for his future but as a signal to others still in the forest. “If the government fulfils its promises, it will show those still in the forest that surrendering is worth it,” he said.

‘Mixed concerns’

In Bama, where the scars of the insurgency remain fresh, community leaders expressed mixed concerns about the arrival of former Boko Haram members. Alhaji Usman Mustapha, a community elder in Bama, said, “We believe in second chances and forgiveness, but this influx of former Boko Haram members who bypass the rehabilitation program is troubling. The official process exists to ensure they are psychologically and socially ready to reintegrate. Without it, the community is left uncertain about their intentions and readiness to coexist peacefully.”

Usman added, “The government needs to do more to streamline these processes and reassure us of our safety.”

Amina Waziri, a trader in Bama, echoed similar concerns. “We see them [former Boko Haram members] every day, joining us in the market and trying to blend in. Some of us are scared. We don’t know if they are genuinely repentant. We need transparency. Who are these people, and why didn’t they go through the programme like others? The government must address this for our peace of mind.”

In Konduga, a community that has also suffered heavily from the insurgency, leaders have highlighted the risks of bypassing official rehabilitation. Shehu Ali, a religious leader in the community, noted that “Rehabilitation is not just about skills. It is about healing, reconciliation, and ensuring they are truly committed to peace. Those who bypass the programme undermine the trust we are trying to rebuild. The government and security agencies must act decisively to manage this issue before it becomes a bigger problem,” he said.

Ardo Musa, a herder in Konduga who lost livestock in a Boko Haram attack, expressed his frustration. “It feels like our pain is being overlooked. We forgave those who went through rehabilitation, but these new arrivals? We don’t know their stories or if they are truly repentant. The authorities must engage us, listen to our concerns, and involve us in the process,” he said.

‘It takes time to build trust’

The narrative is no less complex in Maiduguri, the epicentre of counter-insurgency efforts. Community members stressed the dangers of circumventing rehabilitation.

Mammadu Grema, a community leader and local trader in Jere, said, “Bypassing rehabilitation not only endangers the community but also diminishes the integrity of the reintegration process. We must involve communities at every stage, like identification, reintegration, and monitoring, to avoid suspicion and potential backlash. A community-driven approach will foster mutual trust and ensure sustainable peace.”

A lawyer in Maiduguri, who requested anonymity, told HumAngle that the lack of accountability fuels his concerns. “We are told to accept them, but how do we trust them when they bypass the system? If the government wants us to coexist, it must provide assurances, background checks, monitoring, and open communication,” the lawyer noted.

David Sparks, Director of Operations at Red Latitude Nigeria, who has extensive experience in security matters in conflict-affected regions, weighed in on the issue: “The community? Is it bad for them to be cautious? It takes time to build trust. But everything falls apart with only one incident and one suspicion. The safety of the entire community is at stake, not just reputation.”

He elaborated on the challenges posed by the irregular reintegration of former fighters. “As communities attempt to recover, this kind of uncertainty keeps emerging. People no longer know who they can rely on. There are significant gaps in the psychological, sociological, and logistical aspects of former combatants’ absence from programmes designed to screen and rehabilitate them. Let us be clear: the programmes have little chance if communities cannot trust these mechanisms.”

Sparks also warned about the long-term effects. “The dangers spread when former fighters avoid the appropriate channels. Insider threats, covert recruitment, and re-radicalisation are all possibilities. Then there’s the social pressure—resentment festers, mistrust increases, and the community’s fabric begins to rip. We are putting everyone at risk of failure if we are unable to assist these people in reintegrating successfully,” he said.

HumAngle’s efforts to obtain official responses on the issues raised by the locals and even repentant insurgents have so far been unfruitful. Letters were sent to the Nigerian Army and the Borno State Commissioner for Information and Internal Security, seeking insight into the challenges and strategies surrounding the rehabilitation and reintegration of surrendered Boko Haram members. However, as of the time of filing this report, no responses have been received.

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center as part of a series interrogating the state of democracy in some of Nigeria’s resettled communities.

The article examines the complex lives of former Boko Haram members, shedding light on their recruitment, experiences, and attempts at reintegration into society. It highlights individual stories, including Abubakar Adam and Rawa Ali, who voluntarily left the group, faced challenges upon return, and received little to no government support.

Other narratives, such as Falmata Abba and Aisha Mohammed, portray feelings of regret or relief about leaving the insurgency, while Rukayya's story revolves around health challenges.

The article emphasizes the mixed reactions among communities toward these returnees and critiques the shortcomings of Nigeria's deradicalization and rehabilitation programs.

Concerns are raised about trust and security in communities with former insurgents who bypass official reintegration efforts, indicating the importance of comprehensive and transparent approaches to ensure successful societal reintegration and stability.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter