Spike In Terrorism As COVID-19 Worsens Humanitarian Emergencies In Northern Nigeria

Calamities are raining in torrents for the residents. There is a rise in terrorist attacks, abductions and other violent crimes across Northern Nigeria, amid the spread of COVID-19. The already dreadful humanitarian crises are further worsening.

Victims who manage to escape one calamity steadily find themselves down into the rabbit hole of other criminal onslaughts. Under the overwhelming crises, not much help is in sight. For victims of escalating calamities, particularly in Northeast Nigeria, God seems far away.

For aid workers operating in the region, each day’s foray into the communities of the needy and helpless is steadily turning into a reality show on a death sentence. They have recently become targets of abductions and executions by terrorists.

They are frequently designing and harnessing opportunities to be fed with ransom on prime captives. Aid workers particularly fit this brand. Expectedly, many humanitarian organisations have been forced to scale down their services, especially in delivering foodstuff and medical supplies to Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in these Northeast communities.

Dr Allen Manasseh, Director of Media and Publicity for Kibaku (Chibok) Area Development Association (KADA), attested to this.

He told HumAngle that humanitarian services in Borno State recently came to a halt but had been partly revived. “Right now, they are only going to places that are not really on the red line so that they don’t risk the lives of humanitarian workers and pilots,” he explained.

HumAngle investigations revealed that in areas like Rann, Baga, Malumfatori and Marte, considered as red zones, the populations of vulnerable dwellers in those communities are growing desperate. They are hungry, exposed, medically in need, yet cannot receive much-needed aid.

Within 2020, by July 24 specifically, over 6,800 people, including over 1,500 civilians and 620 security personnel, have been killed as a result of insecurity in Nigeria and over 1,200 have been victims of kidnapping. Data from the Nigeria Security Tracker indicates that the number of deaths recorded in April was the highest since March 2015. A HumAngle examination of the data further reveals that a dominant percentage of the fatalities are in parts of Northern Nigeria.

A decade-long battle with insurgency, banditry and communal clashes has set Nigeria up for the depressing characterisation as one of the world’s most severe humanitarian disaster sites. Contending with these is already an overwhelming burden. To further be struck with additional global health pandemic that exposes potentially millions of the people under life-threatening conditions stretches the disaster beyond full grasp.

According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the number of people who need urgent assistance in the Northeast rose from 7.9 million in January 2020 to 10.6 million following the outbreak of COVID-19. Also, people affected by food insecurity in the region are seen to increase from 3.7 million to seven million.

The European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO) recently estimated that 1.2 million people affected by insurgency in the country lacked access to aid, having been cut off from possible aid by conflict, threats of attack, and restrictions on movement. Experts fear that if the state of security does not improve soon, significantly increased rates of food shortage, health challenges, displacement and death will worsen in affected communities.

Unsafe roads, airspace

The presence of insurgents and the frequency of ambushes against travellers have rendered a significant stretch and categories of highways and other roads in the Northeast unsafe for urgent aid to reach vulnerable populations. Many organisations, to reduce the risk of moving employees from one location to another, prefer to engage locals. This approach is, however, not airtight.

HumAngle’s investigation found that some of the aid workers got employed using illegally procured documents from Local Government authorities certifying them as indigenes, a major consideration for employment. The practice, our investigation shows, is a reflection of the desperation for jobs among young people. These workers then have to regularly travel long distances to see their family or return home without the knowledge of their employers.

Since not all aid workers can work from their original location, there are others whose jobs require that they travel from time to time to areas actively ravaged by insurgency. Because of this, helicopter transportation services are provided by the United Nations Humanitarian Air Service (UNHAS) to convey workers, but even this does not cover much of the areas of critical need in the region.

In Borno State, the helicopters’ possible destinations include Pulka, Gwoza, Damboa, Ngala, Bama, Kala Balge-Rann, Banki, Monguno, Dikwa, and Damasak.

To visit areas outside of the locations covered by the helicopter service, humanitarian workers fall back to the use of the roads but generally in compliance with regularly updated travel advisories and careful plans. But attacks from terrorists and bandits cannot easily be predicted.

In June, five aid workers were abducted by the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) along Monguno-Maiduguri Road in Borno State and last week, and the group released a video clip of its execution of the aid workers. Apparently, the execution followed failed negotiations.

Meanwhile, air travels are not entirely safe either. A UNHAS helicopter came under fire resulting in “serious damage” in July in Damasak as it was returning to Maiduguri, the Borno State capital.

On July 29, the convoy of the Borno State Governor, Prof. Baba Gana Zulum, was ambushed in Baga during an official state tour to connect with his people. The heavily guarded convoy did not prevent ISWAP, a faction of Boko Haram, from attempting an attack on the entourage.

Zulum thereafter showed his displeasure over the security situation in Baga town, saying that despite the presence of the military in the town, the troops were still unable to secure the area.

He was quoted as saying, “You have been here for over one year now, there are 1,181 soldiers here.

” If you cannot take over Baga which is less than five kilometres from your base, then should we forget about Baga?

” I will inform the Chief of the Army Staff to redeploy these men to other places that they can be useful.

“You people said there’s no Boko Haram here, then who attacked us? I doubt if there is any Boko Haram in this town, I can go in and sleep here,” Zulum added.

A military commanding officer in the trending video of the incident could be heard assuring the governor that there were no Boko Haram insurgents in the town.

Baga is located close to the shores of Lake Chad, off the northeast flank of Kukawa town in Kukawa Local Government Area.

The governor was in the town for the reopening of Monguno- Baga highway to commuters after two years of closure.

In June, Borno State Commissioner for Reconstruction, Rehabilitation and Resettlement, Mustapha Gubio, said the ongoing Boko Haram insurgency was preventing the execution of development projects in five of 27 local governments areas in the state.

Reinforcing that concern, Manasseh said “the truth is a few kilometres outside Maiduguri; there is no community, no local government headquarters, no town that is safe for people to go freely and come back. Majority of these roads are not in use, so all the people moving from Maiduguri, for example, to Damboa have to be airlifted, including the volunteer staff.”

Relying on locals and the inability of staff of NGOs to be at locations where aid is needed has widened the gap between givers and receivers of aid.

“Monitoring and evaluation are central to humanitarian assistance, a situation where staff cannot oversee the distribution and delivery of aid; it’s suspended. This is usually the case in Northeast Nigeria,” said Zara Al’Amin, an aid worker with an international agency in Maiduguri.

Aside Gwoza town, villages such as Gava, Ashigasgiya, Arboko, Ngoshe in Gwoza Local Government Area remain inaccessible to humanitarian assistance.

In Damboa, there are communities under Boko Haram occupation such as Talala, Foro, Azur, and Multe with populations. The list goes on, including Abadam, Gubio, Marte, Ngala, and Dikwa local government areas where communities survive at the mercy of Boko Haram insurgents.

The use of helicopters helps with the safe delivery of essential services to critical areas, but there are not enough to meet the needs of humanitarian workers. The few available choppers have to be scheduled, sometimes weeks ahead. There is then the added problem of increased scarcity in recent weeks, which has frustrated efforts to deliver food supplies to IDPs as well as other essential items forcing many to risk travelling by road.

“The truth is the state government has abandoned its primary responsibility to attend to the health of IDPs. So, without the helicopters moving those cargoes, they won’t have access to good medical care,” Mariam Bulus (not real name), who works with an international humanitarian organisation in the Northeast, told HumAngle.

She noted that air travel saved time and prevented civilians from getting abducted or killed by Unexploded Ordnances (UXOs) and Improved Explosive Devices (IEDs).

Diminishing excitement to work in NGO/INGOs in Borno

Despite growing unemployment and poverty levels, many families are putting pressure on their loved ones to either resign or decline job offers by local and international non-governmental organisations because of the high risk of abduction and execution of staff of such organisations by insurgents.

“Because of the increased frequency of attacks these days, some aid workers are resigning their jobs, and that is a dangerous trend at play.

“By the time NGOs start advertising openings for employment and people are not turning up to provide services, then the end has come,” Manasseh added.

To avoid loss of lives through travelling, Manasseh urged organisations providing humanitarian support to, where possible, train and actively involve members of beneficiary-communities.

“The Nigerian labour organisations must step in to ensure that young people that are being engaged by aid organisations should be employed directly and must get health and life insurance,” said Al’Amin

According to Al’Amin, there is a new awakening whereby many young people are now reading their contract letters beyond the figures, and asking questions about their safety and other rights and privileges.

Vulnerability to COVID-19

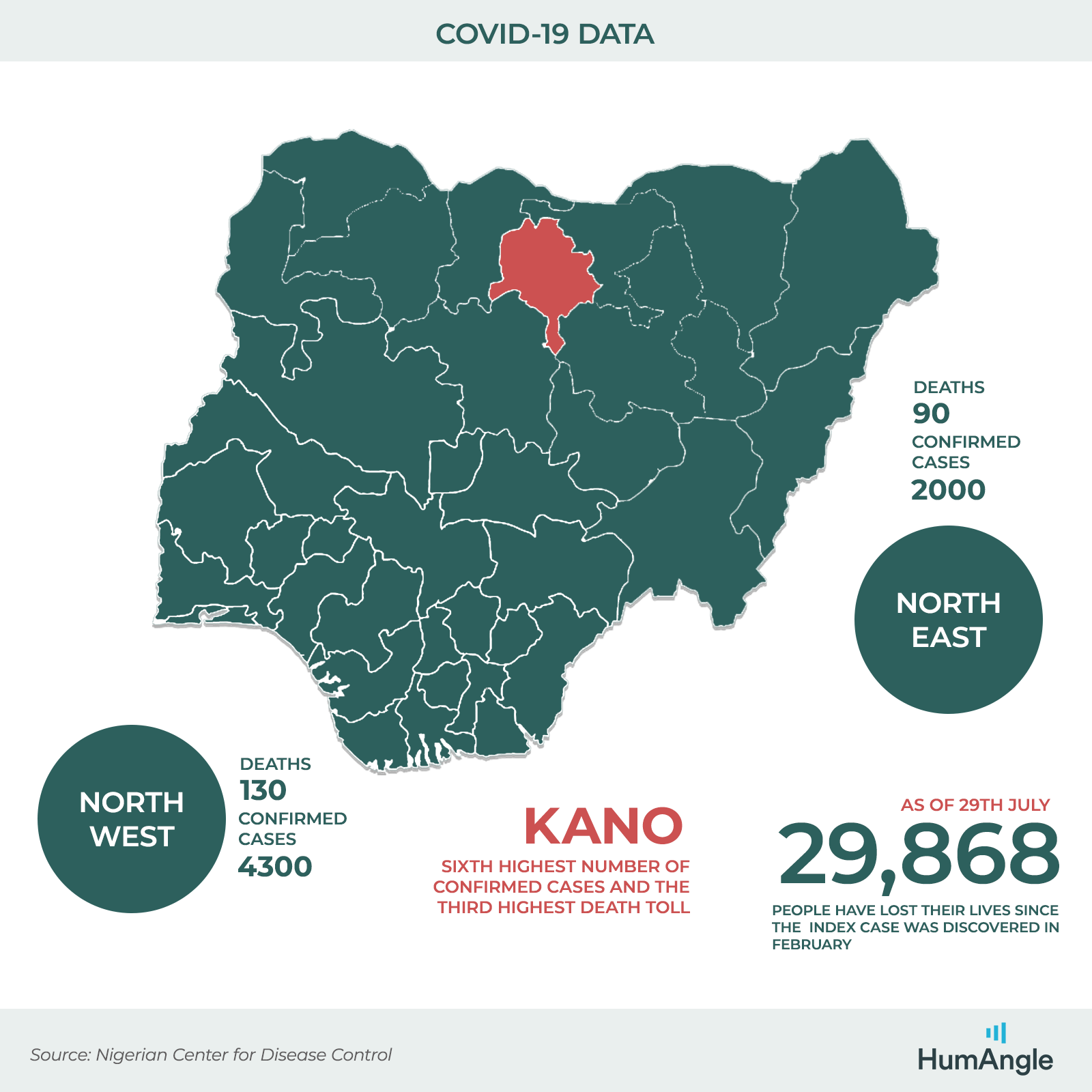

Statistics from the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) show that, as of July 29, the COVID-19 fatality in the country stood at 868 people. In the Northeast, there are over 2,000 confirmed cases, with nearly 90 casualties. In the Northwest, confirmed cases exceed 4,300 with about 130 deaths.

Many believe these figures understate the actual spread and impact of the virus, especially in a place like Kano where there were reports of widespread, controversial deaths. Nevertheless, the state currently has the sixth-highest number of confirmed cases and the third-highest death toll.

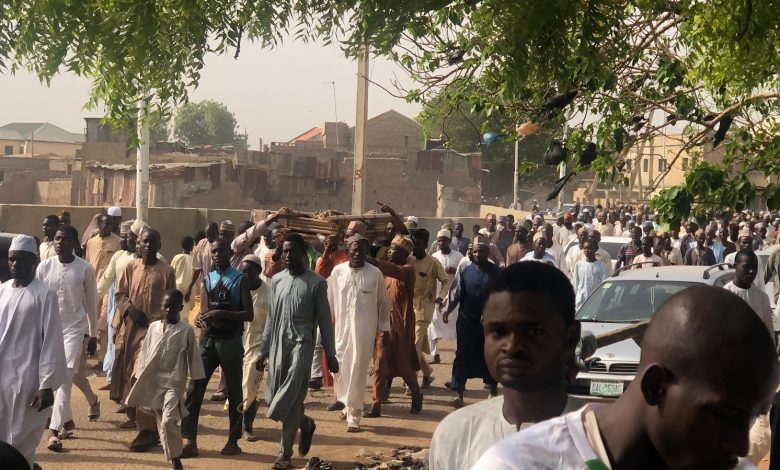

Despite these numbers, adherence to safety measures, including physical distancing and the use of face masks, appears to be the exception, not the norm, in many parts of the North. Manasseh, who has visited several teaching hospitals in Borno said some doctors attended to patients without the necessary personal protective equipment.

“In fact, you look odd when you are wearing masks in Maiduguri. People look at you in some places as if you are strange,” he said, adding that many believed the pandemic was a hoax and an opportunity by government officials to siphon public funds.

“I asked a lot of people when I went to the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital, why they were not properly geared up and observing social distancing. The response was, even our isolation centre is empty; nothing is in it. So, they don’t believe that COVID is real.”

HumAngle visits to a few public places, including public buildings in some Local Government Areas, confirmed Manasseh’s worry. There seemed to be nothing to indicate that people were aware that a public health challenge is ravaging society. The well-rehearsed protocols of handwashing with soap under running water, masking up and social distancing appear totally alien.

Though he has seen the Northeast Development Commission distribute protection kits to some hospitals and agencies, the intervention cannot get to everyone as many of the clinics, especially those owned by the government, “are not even functional”.

HumAngle reported on Tuesday, July 28, 2020, that internally displaced persons in Borno are rendered vulnerable to the pandemic owing to inadequate health facilities. Arising from the newspaper’s interviews with many IDPs, the incidence of widespread ignorance and misconception seems to run deep. The rise in violent crimes makes it challenging for grassroots orientation exercises about the pandemic to be carried out.

The curse of the rainy season

The rainy season which, in Northern Nigeria, lasts between mid-May and September, comes with fresh challenges. Flooding makes various communities even less accessible to aid workers.

The Nigeria Hydrological Services Agency (NIHSA) cautioned on Tuesday that “August and September are very critical for flooding in Nigeria.” Already the ugly impacts of flooding are showing as many states have recorded fatalities and loss of properties to the disaster. Last year, among the 13 states projected to witness increased flooding by the agency were Adamawa, Benue, Kebbi, Kogi, Nasarawa, Niger, and Taraba.

Frequent rainfall, accompanied by a dramatic rise in health challenges, especially malaria and cholera, adds to the growing humanitarian crises in Northern Nigeria.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) had warned in May that the risks presented by malaria, pneumonia, diarrhoea in developing countries “far outweigh any threat presented by the coronavirus” if routine healthcare is disrupted.

Continue reading …

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter