Soldiers Making Millions From Unlawfully Seized Farmlands In Nigeria’s North East

“It is very disheartening to see my land being used by the very people who are supposed to protect me and my community.”

Yidhe Raymond fled her home in Pulka after a terror attack in 2014 that took her husband’s life. She also lost her eldest son to the conflict, which has ravaged northeastern Nigeria for over 14 years. She escaped to Maiduguri, the capital of Borno, about 100 km away, and stayed in a displacement camp. Five years later, she decided to return to Pulka following moves by the government to resettle displaced people back in their ancestral homes. She had hoped for a fresh start. But what she found instead was a rude shock.

Soldiers had taken over her farmland.

Despite her numerous pleas for them to return the land to her, she has been denied access. She is frustrated, and this experience has only added to her hardship and trauma.

“Before the insurgency, I used to harvest more than 20 bags of groundnuts from my farm, and this was the main source of income for my family,” said 55-year-old Yidhe.

“But now, after returning, I found that the soldiers have taken over my farm, and I have lost my livelihood. It is very disheartening to see my land being used by the very people who are supposed to protect me and my community. The military have been using my farmland for more than four years and yet are not moved to give me back this year, even after begging them countless times.”

Pulka is a community in Gwoza, Northeast Nigeria, surrounded by rolling hills and lush green fields. The Sambisa Forest, Mandara Mountain, Ngoshe Hill, and Gwoza Hill encircle it. The lands are rich and fertile for agriculture. It’s been the home for the Mandara people for generations. But when the Boko Haram crisis broke out in 2009 in Maiduguri, the violence rippled through the region.

In 2014, the terror group stormed Gwoza and declared the town its headquarters. Surrounding communities, including Pulka, also suffered terror attacks that led to deaths, abductions, and great destruction. This triggered a wave of displacement in the area. Many people fled to Cameroon, Maiduguri, Adamawa, and other places for safety. Less than a year later, the Nigerian Army recaptured both Gwoza town and Pulka. It established the 121 Batallion in Pulka and dug trenches around it, allowing humanitarian workers and internally displaced people to access and settle in the fortified community and, eventually, the return of locals who previously fled the violence. But the returnees find that their hometown is not as they left it.

Based on interviews with several security sources and multiple victims, HumAngle has established a trend of military officers abusing their power to confiscate farmlands belonging to victims of the Boko Haram conflict and returnees in this community.

Locals who used to live in camps created for displaced people face a new challenge of rebuilding their lives without access to their land, which is a vital source of livelihood and sustenance for many of them. While security agents have seized some of the farmlands close to the town, those further away are unsafe because of the presence of terrorists.

The military officers allegedly use the farmlands to grow crops for their own profit, while the original landowners struggle to provide for their families. This has led to feelings of resentment towards the Nigerian Army, whose personnel are seen as taking advantage of the people they are supposed to protect. In one case of land seizure by a high-ranking Army officer, HumAngle calculated that annual proceeds from the sale of crops harvested should be about ₦18 million ($23,000).

‘They let us suffer’

The number of people living with food insecurity in Pulka is alarming. The bulk of the problem results from the Boko Haram conflict and the Borno state government’s early resettlement agenda, which have left many returnees with little to survive on and no sustainable livelihood.

Borno is the state that has been most severely impacted by the humanitarian fallout of the Boko Haram insurgency. Approximately 77 per cent of the 2.4 million internally displaced individuals recorded in the Northeast as of March 2023 were in Borno. About 8.3 million people in the region require assistance from humanitarian organisations, but in pushing for the resettlement of IDPs, the state government has prevented aid organisations from supporting people at various camps in order to encourage economic independence. But many resettled IDPs and returnees are finding life difficult in the circumstances.

Earlier this year, the International Crisis Group stated that the government had failed to provide a sustainable economic atmosphere for resettled IDPs to rebuild their livelihoods. The report highlights the persistent threat of attacks by armed groups, which has made it difficult for IDPs to return to agricultural activities.

Scarce farmland, scarce housing, and shortage of job opportunities are among the problems returnees have encountered in Pulka town, with many now facing secondary displacement as there’s limited or no humanitarian assistance. Though the inhabitants have been resettled for several years now, many still lack basic needs such as water, school, and healthcare.

Farm seizures by the military make matters even worse.

When Jigga Bitrus, 46, returned to see the military in possession of his farm, he spoke to one officer about regaining custody, but he kept brushing him off and sending him away.

“We know the soldiers are working hard to protect us from the armed group, but letting us suffer because of their operation in our town has created more hunger. The soldiers have taken the farms close to us in the town, while the ones that are far from us are not accessible because Boko Haram are within the locations. We are helpless.”

Many other returnees with similar experiences feel their rights are not being respected and are calling for support from the government and international organisations. The loss of the land is more than just an economic blow for the communities in Pulka. It also affects them emotionally because of deep cultural and historical ties.

Another victim, 56-year-old Duwara Daniel, had depended on farming to provide for his family for over 20 years. He planted beans, groundnuts, and sesame, often harvesting at least 20 to 25 bags of each crop. Now, without his land and humanitarian aid, he has no idea how to get by. The only land open to him is in a hard-to-reach area that is prone to terror attacks.

“I survived on aid from an organisation, but they left Pulka last year and stopped receiving support,” he said.

Vincent Foucher, a conflict expert and Senior Research Fellow at the National Centre for Science Research (CNRS) in France, says, understandably, the military has an edge to do business in communities like Pulka. They have capital, are able to move around, and can provide some safety.

“Also, they can bend the rules, forbidding cultivation in certain areas that they then use, or loosening the curfew for their farmhands. So some military use this edge to engage in various businesses,” he explained.

But when they use land belonging to returnees in a place where there’s a scarcity of arable land due to ongoing hostilities, it raises ethical and legal concerns and can lead to serious consequences.

Without access to their land, the returnees are unable to grow crops, which have been their main source of income for generations. This can lead to a cycle of poverty as they struggle to meet their basic needs and provide for their families. It can also lead to malnutrition and health problems as they may not have access to enough food or money to buy medicine.

Foucher said the action of military officers in Pulka could trigger another wave of displacements, especially considering that “the lack of economic opportunities and basic services like water, agriculture and education is making resettlement more challenging for returning families”. He shared the example of resettled families that have sent their children back to Monguno and Maiduguri because there are no schools available in their new communities.

“Without access to land for farming, many returnees may find it impossible to stay in their new communities and may end up leaving again,” he added.

Besides this, the trend could also pull back successes recorded in the country’s counterinsurgency programme by eroding the trust people have in the authorities and driving support for non-state actors.

The government and military have made important efforts to improve the counterinsurgency picture in Northeast Nigeria in recent years, said Dr Ed Stoddard, an associate professor in International Relations and Contemporary Security at the University of Portsmouth.

“However, instances where civilians are wrongly denied access to their land risk undermining these efforts and playing into the hands of armed groups like ISWAP, who will gladly present state actors as corrupt. Worse still, if populations are deprived of access to farmland, they may conclude that the only option available is to farm in territories where the armed groups have influence, which may expose them to tax demands from militants (and violence if they don’t pay). Good governance in land management thus serves everyone’s interests and works against the strategies of the militants.”

He urged that the people’s concerns should be addressed and their rights respected to prevent further instability.

“The loss of access to their land not only strips the returnees of their primary means of earning a livelihood, it also takes away their means of providing for their families. Without the ability to grow crops on their land, the returnees will be caught in a cycle of poverty. In addition to food insecurity and the health risks that can come with that, there are also social consequences like increased crime, domestic violence, and child labour.”

HumAngle has made several attempts to get a comment from the Nigerian Army spokesperson about the allegations against officers in Pulka, but the questions have gone unanswered.

The problem is from the top

The seizure of farmlands belonging to locals is not just done by junior officers. HumAngle gathered that high-ranking personnel are often pulling the strings. A military source, who asked not to be named for fear of reprisal, stated that soldiers are usually authorised by their commanding officers to engage in the land grab.

“This practice has been happening here for more than four years, but there was no sanction by the Army. This is against the code of conduct for the military,” the source observed.

The source, who was also involved in the practice, said he had to follow orders despite feeling bad for the returnees.

He accused a high-ranking military officer of taking possession of hectares of land belonging to returnees and exploiting them for personal gains. This has gone on for over four years now in Pulka, he said.

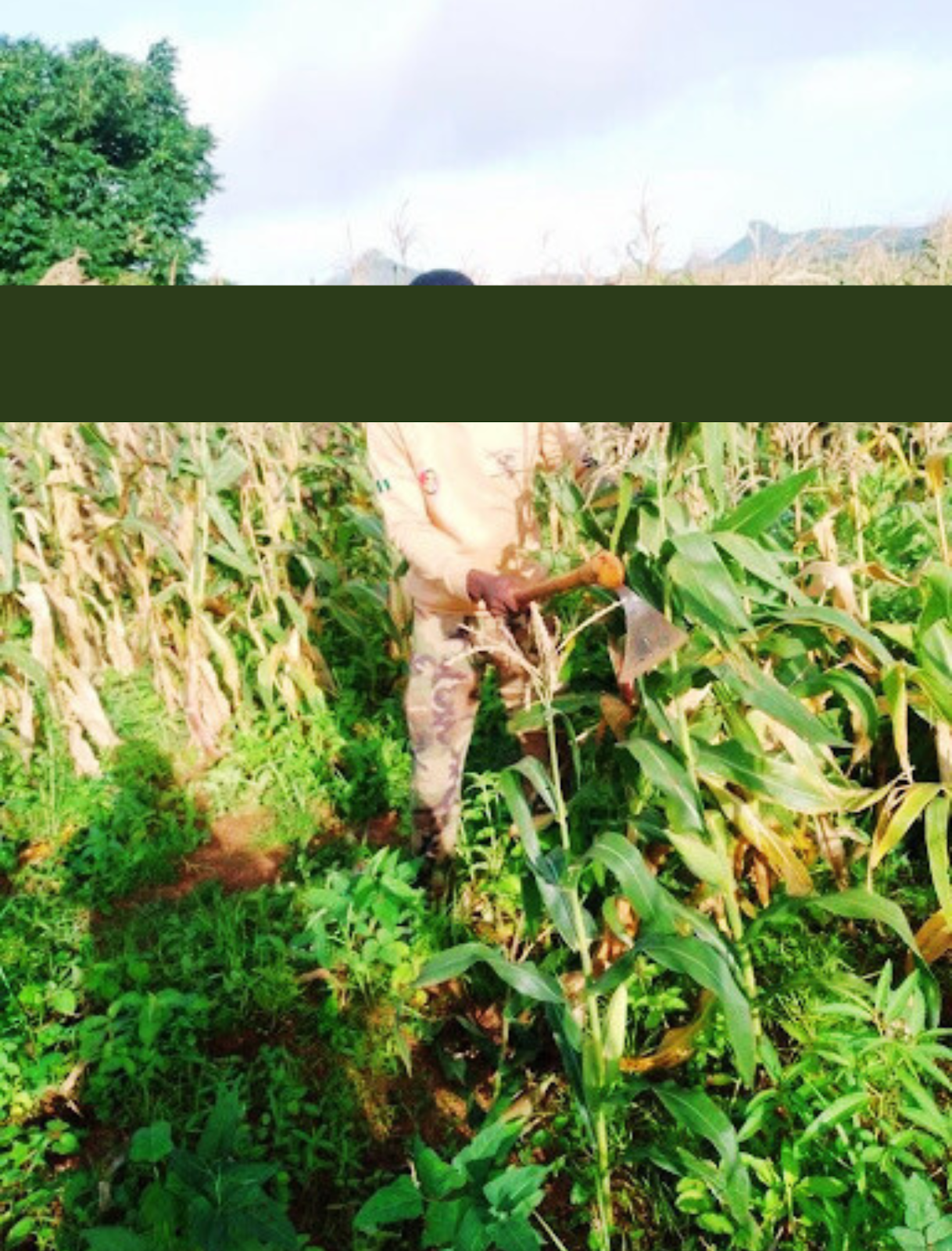

The confiscated farm is a vast expanse of land located by the road stretching about 5 kilometres through the dusty landscape and towards Kirawa. It is filled with rows of bean plants. In the distance, birdsongs and the rustling of the wind through the leaves can be heard; it is a hub of activity during the rainy season.

“The farm employs a number of local workers who are mostly IDPs. They help with planting, harvesting, and sorting the beans,” one of the workers informed us.

There is a temporary storage facility towards the north of the farm where the harvested beans are kept until they are transported. Soldiers, estimated to number between 20 and 30, are assigned to secure the location during clearing, planting, and harvesting.

A Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) officer, who wishes to remain anonymous, said he was part of the team guarding the farm and tasked with paying and resolving issues related to labourers. The workers were paid a daily wage of ₦1,000 for up to seven hours of work, possibly receiving a 50 per cent increment during harvest season due to the added workload.

“Numerous trucks carrying bags of beans leave the town after harvest, escorted by soldiers, with no one knowing their destination,” he said.

According to sources within the military and CJTF, the high-ranking officer’s farm produces between 250 and 550 bags of beans each year. If we work with 400 as the average, that means the annual sales of the produce would fetch ₦18 million ($23,400), considering the current value of one bag of beans in the local markets.

Since work has been going on for the past four years, that would mean sales should be around ₦72 million ($93,400) in total — just from this one farm that the officers are not accountable for.

“Last year, the farm had a bumper yield. I can’t put a number on how many bags of beans were harvested, but it was a lot,” said an IDP at the Pulka-based Damara camp who was hired to work on the farm.

“We were supposed to work on the farm for two weeks during the harvest season. But we ended up working for three weeks because there was so much work to be done. It was hard work all day long, but I was glad to have the opportunity to earn some money.”

Appeals fall on deaf ears

Khadijah Ali, 52, fled when Boko Haram attacked Pulka town in 2014 and spent years living in the Minawawo refugee camp in Cameroon before finally returning to Nigeria in 2019. Upon her return, she found that soldiers had started to use her land for their own farming activities.

“It felt like losing everything all over again,” she said.

She was denied access to her farmland, located along Kirawa Road, despite her attempts to reclaim it. According to her, the soldiers claimed the land was too close to a security perimeter and, therefore, off-limits. Khadijah spoke of her frustration and anger at the situation, saying she felt betrayed and neglected by the government.

“I’ve lost everything,” she lamented.

Umani Dugja, 43, also said the soldier she found on her farm ignored her pleas. She had inherited the land from her late husband, but without access to it, she misses the stability that came with being in a displacement camp. “At least there, I had access to food every month, and my children’s health was taken care of by NGOs,” she explained.

“I even received a small amount of money to start a business. But now that I’ve returned to Pulka, I have no business or farm to work on. Even after crying to the soldier, he still turns a deaf ear to me.”

In the case of Juliana Ishaku, 55, who had also sought refuge in Minawawo, she saw that military officers had built a small storage shed for their farming supplies on her land.

After making several unsuccessful attempts to reclaim her farmland, her health started to deteriorate, and she developed an eye problem that impaired her vision. Even in her weakened state, she continued pressuring the soldiers to return her land. When they saw her condition, the soldiers relented and allowed her and her grandchildren to plant on a small portion — the rest of it still used by them for their groundnuts.

“The soldiers are doing good work. They helped me in the Minawawo refugee camp. They gave me food to eat when I was there. They also brought me back to Nigeria. I told them, you helped me when I was suffering. If you don’t want me to farm here, I won’t go against your decision and may God help you in your duties and also protect you in Jesus’ name,” Juliana recollected her conversation with the soldiers.

When Nali Yava, 65, confronted the soldiers on his farm, they told him they could not let go now. They had already paid labourers to work on the land and had sprayed it with pesticides and herbicides. Nali felt helpless and uncertain about what to do next. He had saved up his pension earnings for three months to use for farming this year.

Like Juliana, he was later allowed to plant on a small portion of the land. He alleged that the soldiers gave what was left of the farm to their girlfriend. “Kai duniya! (oh this world!), oh Boko Haram!” he lamented.

Alhaji Ibrahim Ali Pulka, the town’s district head, confirmed to HumAngle that he has received many complaints from returnees about security personnel taking over their farms and said his attempts to intervene have not been successful.

“The military has not responded to my inquiries, and the returnees continue to face problems every rainy season.”

Against the law

The actions of security personnel in Pulka violate both national and international laws.

Charles E. Uche, a lawyer and development expert, points out that the agents are breaching at least the Constitution, Armed Forces Act, Land Use Act, African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (Kampala Convention), African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights, and Rome Statute establishing the International Criminal Court (ICC).

“These regulations sternly prohibit seizing land from citizens, even during times of conflict, save in a few specific instances that clearly don’t apply in this situation where the military are confiscating [immovable] properties belonging to civilians fleeing conflict for their personal gains,” he said.

Nigeria’s 1999 Constitution stipulates, for example, that no moveable or immovable property shall be compulsorily possessed or acquired except as prescribed by law. Even in such cases, compensation must be paid, and the owner is entitled to take legal action to determine their interests and how much they are owed.

This is corroborated by the Land Use Act.

Uche added that sections 104 and 114 of Nigeria’s Armed Forces Acts, which deal with offences against civilians, penalise such misconduct by members of the military members.

“The Nigerian Penal and Criminal Codes (Section 15) do not exempt the military from their application. The Armed Forces Act also punishes stealing from and lodging in civilian premises, even though it is not directly relevant in this case,” he explained.

“Chapter 4 of Nigeria’s IDP Policy made pursuant to the African Union Kampala Convention, in which Nigeria is a signatory, explicitly mandates the government to take protective action on behalf of the victims of internal displacement against threats by others or stemming from their displaced situation, and to ensure their sustainable return.

“More so, although not squarely applicable here but indicative of the graveness of this unlawful activity by some members of the Armed Forces, Article 8(2) (e) (xii) of the 1998 ICC Statute prohibits and designates as a ‘war crime’ the seizure of property – of an adversary – unless such seizure be imperatively demanded by the necessities of the conflict in non-international armed conflicts.”

Uche implored the Borno state governor, Minister of Defence, Armed Forces Council, National Human Rights Commission, and other key stakeholders to quickly intervene on behalf of the returnees, who are pushed further into poverty by the abuses.

The law is not the only thing we should be concerned about, said anti-corruption activist and founder of Follow the Money Hamzat Lawal, who described the allegations against army personnel as deeply disturbing.

“The military is essentially trusted to restore the security of lives and properties in Gwoza, which was ravaged by Boko Haram,” he said.

“The action of a few people who have chosen to abuse this power by forcefully collecting properties, specifically farmland, which is a means of sustenance from the very people they are meant to protect, not only undermines the trust and well-being of the affected individuals but also tarnishes the reputation and erodes the integrity of the military.”

He advised the military to take immediate action, thoroughly investigate the cases, and sanction those found culpable.

“I must reiterate that occupying any public office in any capacity is a call to service, and it is only through upholding the standards of transparency, accountability and ensuring that any abuse of power is checked that the military and, by extension, public offices can regain public trust and confidence in the institutions they represent.”

This report was produced in partnership with the MacArthur Foundation under the ‘Promoting Transparency in Insurgency-Related Funding in Northeast Nigeria’ Project.

Summary not available.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter