‘Slavery’ At The Polytechnic, Ibadan, Where Lecturers Are Paid N19,800 Monthly

Behind the institution’s ranking as the best state polytechnic in Nigeria are a hardworking workforce and multiple stories of grief, depression, and regrets.

Funmilayo* was 28 when she started working at The Polytechnic, Ibadan, as a youth corps member.

In 2015, she was formally employed on a part-time basis as a teaching assistant. According to her letter of appointment, she was expected to “teach for four hours a week at the rate of N5,000”.

Funmilayo, however, works just as much as regular members of the academic staff, if not more. A single mother, she now has two children of school-going age and will be 40 very soon. But her salary has remained N20,000 a month — N19,800 if you deduct taxes.

The Polytechnic Ibadan is a tertiary institution owned by the Oyo State Government. It has well over 200 part-time lecturers (unofficially, teaching assistants), estimated to constitute about half of its academic workforce.

Hoping they would soon be gainfully employed, most of them have worked diligently for a long time — some who spoke to HumAngle have worked as many as 14 to 18 years. They feel stuck and as if the school has robbed them of a huge part of their lives, many of them said in describing their ordeal.

Funmilayo currently goes home at the end of the month with less than N10,000 because of a N150,000 loan she took to pay for her post-graduate studies. She had enrolled with the hope that she would have an upper hand when it is finally time for appointments. Her poor salary, in fact, pushed her to sell some of her properties to keep body and soul together.

Among other work-related expenses, she spends N300 on transportation, sometimes even on weekends. She has yet to pay her house rent of N150,000 this year and her landlord’s threat to evict her hangs over her like the Sword of Damocles. Her salary is just not enough and she is tired of waiting.

“I even told my colleague that I am ready to leave. But then, I have been there for over 10 years. The child I was carrying then is now in Community High School. I keep hoping that things will get better, but it is as if my hope is being cut off. They are just using us,” she says in a tired voice.

The school management has constantly promised to do better, but Funmilayo’s experience suggests that the management cannot be trusted. She was first denied a full-time appointment in 2011 during the administration of F.A. Adeniran and then in 2015 by the Professor Olatunde Fawole-led management.

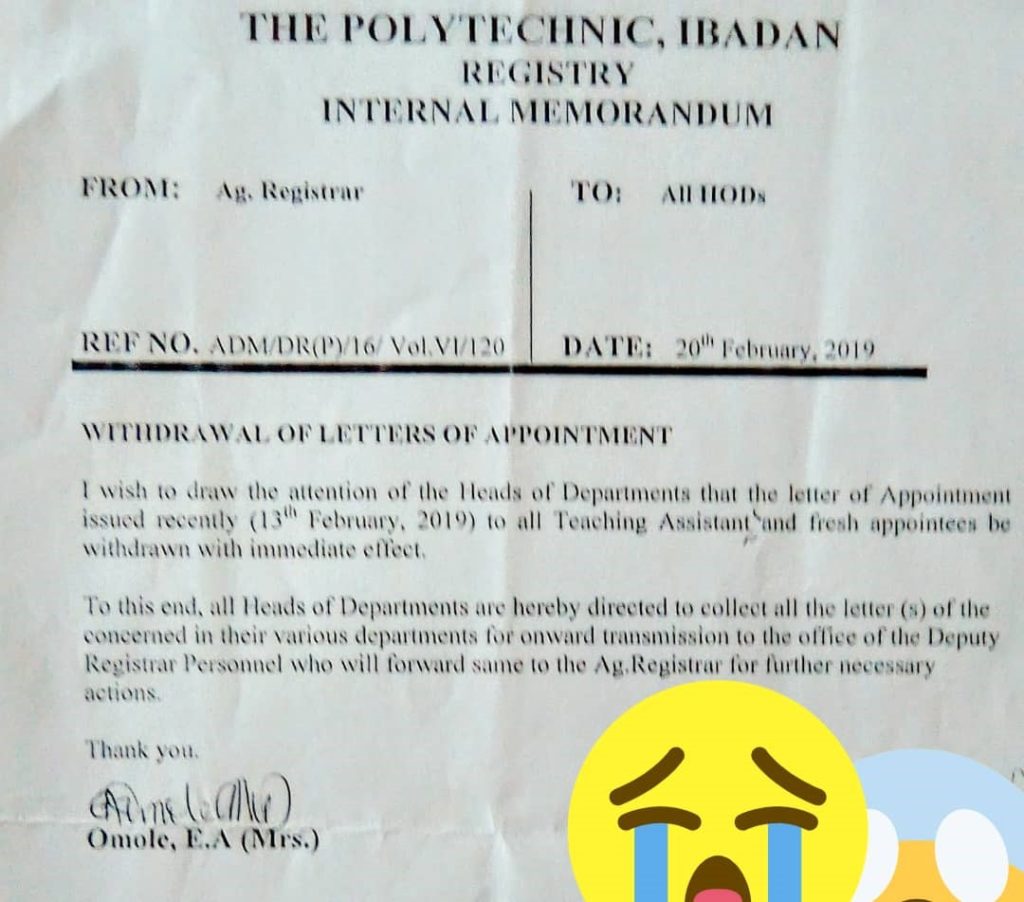

Again, on February 13, 2019, 56 part-time lecturers, including Funmilayo, were given letters appointing them into full-time positions. She was excited! She borrowed N3,750 to get her medical clearance done and a little more to celebrate with colleagues and other well-wishers.

She did not mind, thinking she would comfortably pay back the loans after receiving her first salary. She even went to church and gave testimony. Some colour was finally returning to her life, she thought. But not for long.

She started hearing rumours about a possible withdrawal of the latest appointments but did not think it was possible. People assured her no such thing had happened in the past. In the last week of February, however, she received a call from her Head of Department, who asked for the letter’s original copy and said the management “wanted to do some things about the appointment”. That was the last time she saw the letter. Her faith suffered a huge blow.

“Since then, I have vowed that there is nothing that can happen in my life that would again take me to the front of the altar,” blurts Funmilayo, referring to her testimony in church. “No, no, no… It can never happen again.”

When this reporter called her on the night of November 2, she held some tablets in her left hand and was about to swallow. The stress of invigilating a hall full of about 3,000 freshmen at the polytechnic was starting to get to her and her voice had become brittle. She is also treating arthritis.

“I went to the hospital two Fridays ago to see the doctor. I could not even buy the amount prescribed for me. I just told Kunle Ara (Pharmacy) to sell a third of the dose and that after taking that one, I would return to get the remaining,” she says.

Because of Funmilayo’s underpayment and constant struggle to keep head above water, she also blames herself for her father’s death in 2018.

He called her one morning to complain that he did not have any money, and she promised to send something within the next two days. In the evening, one of his close friends called to ask for help. “Your dad’s friend has been hospitalised,” he declared. He called again the next morning and insisted she came to Oluyoro Hospital. Getting there, she realised it was her dad who needed help. He had lost his speech and had only N95 in his pocket.

“The money could not have transported him home from the church he went to. He needed like N180 to get back home,” says Funmilayo. “The morning he spoke to me was the last time I would hear his voice. He spent like two weeks in the hospital before he died. I think it was because of me…”

A day before her interview with HumAngle, someone informed Funmilayo that she saw her mom— who is aged somewhere between 65 and 68—hawking drinks and sachet water at Gbagi Market, Ibadan.

Before her father’s death in 2018, she had also caught her carrying others’ luggage for a fee to sustain herself. A demoralised Funmilayo had called her sister to the scene and they both wept. She now hesitates to reach out to the old woman.

“If I want to stop her from hawking, do I have anything to give her?” she asks before a long pause. “I believe in God but … eh, my faith is shaking. My faith is shaking.”

Fudged accreditation exercises

Every two to three years, officials of the National Board for Technical Education (NBTE), a federal regulatory body, visit the polytechnic to ensure it keeps to nationally acceptable standards. It does this by assessing the quality of its curriculum, personnel, and infrastructure.

The government body expects the academic staff to have the right mix according to ranking and percentage with relevant higher academic and professional qualifications.

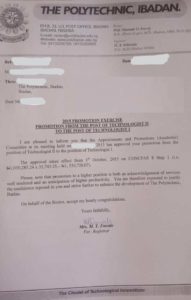

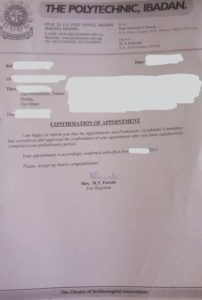

Each time such exercises come up, the school management renews promises to the part-time lecturers about the prospect of regularisation. But it gives them more than fresh assurances. In many departments, the lecturers are also given backdated letters of appointment and promotion, portraying them as regular staff members, to beef up the school’s supposed staff strength. The positions stated in the letters are based on the lecturers’ academic qualifications and the number of years they have spent teaching. If necessary, the names and signatures of past rectors are evoked to make the documents seem credible, according to reports and documents studied by HumAngle.

“They even used to hire total strangers to impersonate lecturers when I first got in, but they don’t do that any longer because they have enough part-time staff,” one lecturer alleges.

His account was corroborated by at least four other part-time lecturers.

Thanks in part to the work of part-time lecturers and how the school presents them, the NBTE ranks The Polytechnic, Ibadan, the best state-owned polytechnic in Nigeria and the fourth-best overall out of 112 schools. This was based on its assessment of the 2015/16 and 2016/17 academic years.

Meanwhile, when the accreditation exercise is over, hardly anything is heard about a possible regularisation till the next NBTE visit. And the few times people have been appointed, such as in 2015, have been allegedly botched by favouritism. Another set of eight people, HumAngle learnt, were also offered an appointment on February 8, 2019, a week to the appointment of close to 60 part-time lecturers. Many of them were observed to have strong connections with former top management officials of the school. And while the second batch of appointments was later nullified, the jobs of these eight staff members could not have been more secure.

This reporter called one Mr Kenneth whose phone number is placed on NBTE’s website for enquiries. He directed us to send an email to the board, adding that “hopefully you would receive a response”. We did not.

Copies of fake appointment and promotion letters

The lecturers alleged that the Oyo State governor, Seyi Makinde, was misled to think his predecessor, Abiola Ajimobi, had hastily appointed people after realising he had lost the election in 2019. This, they claimed, was why he did not reinstate the affected lecturers. But while the senatorial election was conducted on February 23, 2019, the appointment letters were dated February 13 and withdrawn on the 20th.

When HumAngle reached out to Taiwo Adisa, chief press secretary to the governor, for clarification, he directed us to the commissioner for education, Olasunkanmi Aremu Olaleye. The commissioner, however, did not answer calls placed to him on separate occasions. He also did not reply to texts asking for comments.

Suffering and toiling

According to the part-time lecturers who spoke to HumAngle, not only do they work as much as other academics, but they in fact shoulder the bulk of the workload. This is reflected in their sheer population in many of the departments. According to the brochures of the Faculties of Environmental Studies, Financial Management Studies, Business and Communication Studies, and Engineering as well as similar documents gleaned by this paper, the ratio of full-time to part-time lecturers ranged from 1:7 in the Department of Surveying and Geoinformatics to 30:13 in General Studies.

| Departments | Full-time lecturers | Full-time instructors | Part-time lecturers |

| Architecture | 3 | – | 5 |

| Banking and Finance | 9 | – | 10 |

| Computer Engineering | 6 | 1 | 8 |

| General Studies | 30 | – | 13 |

| Insurance | 4 | – | 6 |

| Marketing | 3 | – | 4 |

| Mechanical Engineering | 7 | 8 | 6 |

| Mechatronic Engineering | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Office Technology Management | 3 | 1 | 9 |

| Purchasing and Supply | 5 | – | 6 |

| Surveying and Geoinformatics | 1 | 2 | 7 |

“In most departments, it is the part-time lecturers who work themselves nearly to death,” says Jeremiah*, a lecturer at one of the campus’ largest faculties.

“According to the letter, it is supposed to be four hours a week, but we work like … In fact during accreditation, we have to work overtime. Once my faculty starts examinations next week, I have to be there as early as 7 am, I have to prepare answer scripts, prepare questions, to make sure the exams go smoothly. There are weekends when we have to come to perfect some things.

“We work during normal office hours, 8 am – 4 pm, almost every day. Even if you don’t show up, they will call you: ‘What happened? We didn’t see you,’” he mimics the queries in Yoruba.

Asides lecturing and being part of departmental committees, part-time lecturers also supervise projects, serve as examination coordinators, result officers, level and course coordinators, staff advisers, and do whatever else the Head of Department assigns. Jeremiah is quick to add that the only thing sustaining him is his passion for the job.

“I enjoy doing this thing… but when they want to kill your spirit, you wake up in the morning and feel like,”—he again switches to Yoruba for emphasis—”haven’t I lost everything now?”

Despite the crucial work they put in, part-time lecturers are neither well-compensated nor do they have access to many benefits including campus accommodation, free medical attention for themselves and their family, an annual leave of 42 days, transport allowance, eligibility for promotion, loan options, and research funding opportunities. Instead, some of them are forced to help regular lecturers with their research publications, watching glumly as they step on them in ascending the academic ladder while they remain fixed to a spot.

Adewale*, 37, who has been working at the polytechnic since 2012 is married with two children. Before his marriage, he complemented his meagre salary through various means, including taking tutorial classes. But, with a full-time part-time job and a family to take care of, he is having less and less time for other activities. He has been having a tough time paying his daughters’ school fees, about N9,000 per term for each girl. The school recently sent him an SMS reminder, he says.

His plan was to give N10,000 out of his salary to the school and then promise to pay the balance later. But, as of November 5, his phone had yet to buzz with a credit alert from his bank. It was not the first time. Sometimes, the salary gets delayed till the first or second week of the following month.

“I had to go to about seven or eight schools because I needed to cut my coat according to my size,” narrates Adewale. “So I went to a school that I know, well, they are not actually above standard, but my beggar has no choice. My wife has been trying to add her own bit to whatever they teach them in school.”

He is afraid this method is not sustainable and wonders how he will cope once the girls are admitted into higher classes.

* * *

Despite already getting an MSc degree in 2015, Jeremiah’s case is no different. And if he is appointed today, it will not matter that he has been working as a teaching assistant since 2013. He will have to start from the entry-level, likely Lecturer III, based on his credentials—which will get him a salary of about N120,000. Whereas those offered appointments in February 2015 are set for promotion to the Lecturer I cadre.

Jeremiah, however, does not want to embrace the possibility of getting compensated for his previous eight years of service, having had his hope crushed many times and convinced it would end in disappointment. “They should just pay the deserved salary. Let us start planning for the future,” he suggests instinctively.

“I will be 40 this year for Christ’s sake. At times, I will just sit and I wonder: is it that I want to become a fool at 40? With a salary of just N20,000. Ahhh. No now. No,” he sighs, then lets out a tired, frustrated cry. “We hope through this [report] the government will be able to do the needful and call them to order. This is servitude at the Polytechnic, Ibadan. It is servitude, forced labour.”

Endless tragedies

Sources at the polytechnic shared other stories they had gathered from their colleagues, which they considered even more heartbreaking. When we contacted some of them to independently verify, while they did not deny the accounts, they were afraid to speak lest they endangered their jobs.

Mr Z: He is in his 40s but still single. He cannot afford decent accommodation nor is he able to take care of his junior ones and aged mother. He was among those appointed as an Assistant Lecturer on February 13, 2019. He had shared the good news with his mother and informed her he would get married to his fiance of eight years within the next three months. But his appointment letter was withdrawn a week later—and automatically his plans for marriage too.

Mr Y: His wife needed N300,000 for a medical operation but he was only able to raise N130,000. At the time, doctors and other health workers in government hospitals were on strike. She died after an agonising two weeks in a private hospital, which had been providing palliative care as it waited for a deposit of N200,000. Years after, Mr Y is yet to completely pay off his debts, nor has he recovered from the traumatic loss.

Mr X: He graduated with an upper credit for his BSc and top of his MSc class. He has been teaching part-time classes since 2014 and is hoping to save for his PhD. He has purchased PhD forms on three different occasions but could not pay the tuition of over N150,000 though he was offered admission at the University of Ibadan. He hopes to get the form again for the next academic session and prays he will finally be able to raise the tuition.

Mr W: He does not answer calls from his family members anymore, unable to fulfil his obligations and offer financial support. His counsel to his junior siblings not to engage in cybercrime was met with contempt and mockery. “They asked if I can afford a car, three square meals, or have up to N5,000 in my bank account despite having two degrees,” he told his colleagues. He said he could not come up with a convincing answer. He has become a recluse because of the embarrassment.

Mr V: He is the first graduate in his lineage and was full of hopes for a brighter future when he got a degree. But after six years of serving as a part-time lecturer at the polytechnic, he is single, has no savings, no career progression, and in his words “no prospects”. “Everything is just gloomy and it is because I am the child of a nobody,” he wails. The heat of the COVID-19 pandemic was hell for him. He spent the little money he had on internet subscriptions so he could attend online classes and had to depend on food palliatives donated by the state government. “Keeping my sanity is just by God’s grace,” he says.

Mr T: At the end of the month, he goes home with a little over N1,000 from his salary. This is because money is deducted for a loan of N180,000 he takes every year from a co-operative society. He used this money for his wedding, MSc programme, and pays his house rent with it. He joined the polytechnic nearly a decade ago as a corps member before his part-time engagement. He helped his department float a programme because of a promise of regularisation. The programme was later approved by NBTE’s Board of Studies and was listed by the management as a key achievement. The promise made to him was, however, not fulfilled. Mr T was among the 56 part-time lecturers offered an appointment in 2019. He had rejoiced with his family and did thanksgiving. When it was withdrawn, he became depressed and frustrated. “My self-esteem is extremely low and I am always embittered whenever I think about all the years I have wasted servicing a system that doesn’t seem to reward excellence but nepotism,” he laments. “Teacher-assistantship has affected all facets of my life but I keep hope alive. To have a rewarding career with the Polytechnic, Ibadan is my dream.”

Master-servant relationship

One of the ways through which part-time lecturers make some extra money is by teaching under the polytechnic’s Continuing Education Centre (CEC) programme, which awards diplomas to successful part-time students. Teachers are paid at the end of the semester based on the number of hours clocked in. Each hour of lecture attracts N1,000. But, even here, teaching assistants say they are often ripped off by their superiors, who either get better-paying opportunities or reap the rewards of their own labour.

In April 2015, after he was assigned to facilitate a CEC course, Adewale had been looking forward to his pay after the semester because he needed it to pay for his master’s programme at the University of Ibadan. But when the time came, he was told he was not entitled to compensation because of his part-time position and the nature of the course.

“I am not going to lie, I wept like a baby,” he says. “I had made plans; I had picked up the form at UI and the only thing I was expecting was for them to pay me so I could pay my tuition.”

His programme was delayed by a year and he eventually had to borrow money from another lecturer to pay. Because of the loan, his take-home from the salary was reduced to N6,000 for almost one year.

“The system makes you understand that as a part-time lecturer, your jurisdiction is that, when it comes to work, you take the major bulk but, when it comes to money, you take zero or little. That is how the system works; like one of enslavement,” says Adewale.

He adds that part-time lecturers who step on the toes of core staff members are often punished with getting assigned to less lucrative part-time courses. “—It’s a way of saying if you mess up, we know how to deal with you. It’s like a master-servant relationship.”

Adewale admits that he has had to carry his Head of Department’s bag. Also, he occasionally washes his car and runs domestic errands for him if he “needs to”. It is not something he is proud of, he clarifies. But by being helpful and submissive, he hopes to be in his good books for a time when he would recommend him to be appointed. And it worked. He was one of two lecturers in the department the HOD recommended for assimilation before their letters were later withdrawn.

“It is either you serve and earn a little more or you stay by yourself in your office and earn little to nothing,” he explains.

“These problems differ according to the department. In some, full-time lecturers will put their names and account numbers and the part-time lecturers will be the ones to teach [CEC courses]. So, if the money comes, they will remove a certain percentage for you and tell you it is not your right to take such money. Nobody questions whatever anybody pays. Even if he feels like not paying you for it, you only wallow in silence or you complain—and you can’t complain in front of the person.”

On three separate days, HumAngle called two phone numbers belonging to the institution’s spokesperson, Soladoye Adewole, but he did not answer. He also did not reply to texts requesting for an interview. The polytechnic’s rector, Professor Kazeem Adebiyi, also did not acknowledge or respond to a text sent to him.

‘Do the needful’

All the long-time part-time lecturers want is some dignity of labour and to be rewarded adequately for their work. But they fear that, even if the polytechnic kickstart a fresh process of appointment or regularisation, it may be marred with nepotism and over-politicisation as in previous cases.

They hope that the school management and state government would “just do the needful”.

If they would act too, they had better do so quickly before “it is too late,” says Funmilayo. She often gets enraged when she is addressed as “lecturer” because it feels like mockery, some sort of dramatic irony. On occasion, she would dress up to go to work but then decide to sit it out. This happens whenever she becomes downcast from wondering what she has gained from her years of service.

“And this is a department where we are working more than those who are earning money. This morning, there are two full-time and five part-time lecturers who are invigilating. The HOD would just come to see that everything is okay and then leave the venue. We are the ones working for another set of people to earn.”

When Adewale’s appointment letter was withdrawn last year, he became depressed for months. He had excitedly told his parents, colleagues, and even PhD supervisor about his appointment, and could not summon the courage to inform many of them that he was suddenly back to earning N19,800.

“It is very frustrating… I wouldn’t lie to you… I almost… I almost… ermm,” he is unsure whether to continue, making it obvious he skirts around a taboo topic. “I am a very strong person, but there are things that would happen to you: You have collected the letter, and all of a sudden they are withdrawing the letter from you.”

He finally feels more comfortable expressing his thoughts in Yoruba: “It is enough for a person to commit suicide. I am telling you. It is enough for a person to buy a rope, tie it to a fan, and kill himself.”

Still holding her drugs in her left hand, Funmilayo prays that she is able to get some sleep tonight. Recollecting her experiences has a way of spoiling her mood, she explains.

“I am tired of this particular job. If anything will come out, fine. If nothing will come out, fine. If God wants to do something sef, he should do it on time before it is too late… because it is getting late.”

*The names of the lecturers and a few other details have been changed to prevent them from being identified and maltreated.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter

That was a great job. I was posted there for my nysc and I can say that most of the things said are true