Six Years After, Nigeria’s Safe Schools Initiative Is Unsafe?

Nigeria was again reminded of how unsafe its schools are on the night of Friday, December 11, with the abduction of over 300 students of Government Science Secondary School, Kankara, Katsina State.

The tragic incident brought memories of similar mass abductions of over 276 schoolgirls in Chibok, Borno State, in 2014, and 110 schoolgirls in Dapchi, Yobe State, in 2018.

It raised questions about what long-term plans the government has in protecting schools from terrorists and kidnappers. And one project that stands out as it was specifically aimed towards this end is the Safe Schools Initiative (SSI).

“Return of Katsina boys is wonderful news! Time to revive the #SafeSchool initiative and implement it comprehensively to protect our children,” tweeted former finance minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala on December 18.

Launched in May 2014 following the infamous abduction of the Chibok girls by Boko Haram, the SSI sought to make schools safer for learning.

How? Through reinforced infrastructure such as the construction of boundary walls, deployment of armed guards, staff training, counselling, and the development of security plans and rapid response systems.

The programme also underscored the importance of having community education committees, teacher-student-parent defence units, and the engagement of religious leaders towards the promotion of education.

It was previously supervised by the Presidential Committee on the North-East Initiative (PCNI) before the establishment of the North-East Development Commission (NEDC) that started operations in 2019.

A fund of $10 million was pledged for the project by a coalition of Nigerian private sector leaders, working with the UN Special Envoy for Global Education, Gordon Brown (through the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, UNICEF) and other international organisations.

The Nigerian government had established a Safe Schools Fund to bring together funding from various quarters including grants from donor organisations and a $10 million contribution from the government itself.

But not much has been heard of the project lately.

Four Years After Launch

According to a 2018 Voice of America (VOA) report, stakeholders in the affected region’s education sector were critical of the initiative. Yobe State’s commissioner for education, Mohammed Lamin, said no measures had been taken to secure schools within the state at the time.

“Maybe they may come in the near future to start fencing some of the schools or providing some security equipment to us, but up until this moment, nothing has been done. It is only the state government that has been providing all these things to our schools,” he complained.

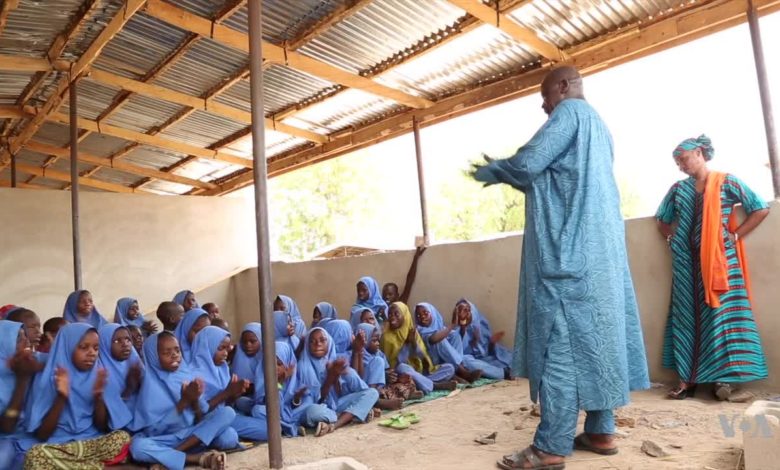

The initiative’s officials, however, told VOA they had deployed resources in establishing learning centres for displaced children, relocating over 2,000 students to safer schools, training teachers to conduct safety drills for their students, and so on.

“Look, we cannot stop an armed invasion of a school. This is not our mandate,” said Geoffrey Ijumba, head of the UNICEF office in Maiduguri.

“We can train the teachers to provide psycho-social support. We can provide uniforms, we can provide school materials, we can provide water at the school, but the protection of the school itself, it’s important that the security agents in the country take over that.”

Query by House of Reps

Following the abduction of 110 schoolgirls in Dapchi, Yobe State, the House of Representatives beamed a searchlight on the SSI and wondered by schools were still not fortified against terrorist attacks.

Shuaibu Abdulrahman, a lawmaker from Adamawa State, said there was no indication schools in the region were secured through the installation of CCTV cameras and high perimeter fences as proposed under the project and asked for the implementation to be probed for possible financial mismanagement.

The dip in momentum in the implementation of the project has been partly blamed on the change in government in 2015, which may have led to a shift in priorities.

“When Nigeria’s new government took power in 2015, many of the Safe Schools Initiative’s activities were not pursued as a policy priority. Campaigners are calling for the initiative to be revived and reinstated,” observed Their World, one of the non-profits that launched the programme in 2014.

Attempts by HumAngle to get comments from the NEDC proved abortive. Multiple calls placed to a phone number associated with the PCNI did not scale through, and an email sent to the commission has yet to be replied.

And the Safe Schools Declaration?

Another step the Nigerian government has taken towards insulating schools from the disruptive effects of insecurity is the ratification of the Safe Schools Declaration (SSD) in March 2019.

Education in Emergencies Working Group Nigeria (EiEWGN) launched the declaration back in April 2017 and has since moved for the provision of quality education opportunities that meet the physical protection, psychosocial, developmental and cognitive needs of people affected by emergencies.

The SSD is a multinational political commitment that allows governments “to express support for protecting students, teachers, schools, and universities from attack during times of armed conflict”. It was launched in Norway in 2015 and, as of November 4, 106 countries have endorsed the declaration.

These countries, in other words, have committed to highlight the impact of attacks on education in conflict and insecurity, promote better systems for monitoring and reporting attacks, promote effective programmes and policies to protect education from attack, encourage adherence to existing international laws protecting education, and fight impunity for attacks on education.

UNICEF is part of the sub-committee tasked with the responsibility of raising awareness and implementing the SSD in Nigeria through focusing its support on access to education.

With the ratification of the SSD, the building of resilience among school children, teachers and communities in some schools has been beneficial in protecting children in Borno, Yobe and Adamawa states from attack.

UNICEF’s education officer, Dr Judith Gwa-Amu, told HumAngle three models were identified by a technical committee as ‘quick win’ interventions and implemented in Adamawa, Borno and Yobe between 2014 and 2016.

She recommended the immediate implementation of this policy, which already gained the approval of Federal Ministry of Education and EiEWGN, in view of the recent school attacks in Katsina.

The Education in Emergencies Working Grouping Coordinator for Save the Children, Badar Musa, says not much was done at first when the SSD was introduced in 2015 till pressure was mounted on the Federal Government.

“We started a pilot project in the North East to see what we can do as humanitarians to strengthen government systems to ensure that schools are protected from attacks and so we are able to work with the children and government staff,” Musa told HumAngle.

From the non-profit’s activities, they learnt from government employees that they want improved welfare in order to better prepare them to support the needs of children. Children, on the other hand, have observed that the absence of fencing around their schools is one of the primary reasons for their vulnerability to attacks.

“One of the schools for the pilot project is Fariya Primary School in Maiduguri, Borno State. When we went there, the school was very close to the cattle market, so all the trucks that brought cattle to that market passed through the school because it was not fenced. The children even recalled an incident where a car ran into a group of students who were playing football, killing one of them,” Musa said.

Asides fencing the schools and providing adequate sanitary facilities, he urged the government to train teachers and school managers on the minimum standards for safety in schools “not only in the northeast but all over the country”.

“If the guidelines on safe school declaration are implemented, then the issue of attack on schools will be greatly reduced,” he emphasised.

“And that is why we are developing this Minimum Standard for Safety and Security Policy. By the time it is passed, every school must put in place some measures without which they will be sanctioned.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter