Silent Emergency: The Unending Cycle of Ethnic and Religious Violence in Nigeria’s Middle Belt

HumAngle explores the ethnic, religious, and environmental roots of the farmer-herder conflict in Nigeria’s Middle Belt, its devastating toll on communities, and the challenges of achieving lasting peace amid cycles of violence and weak governance.

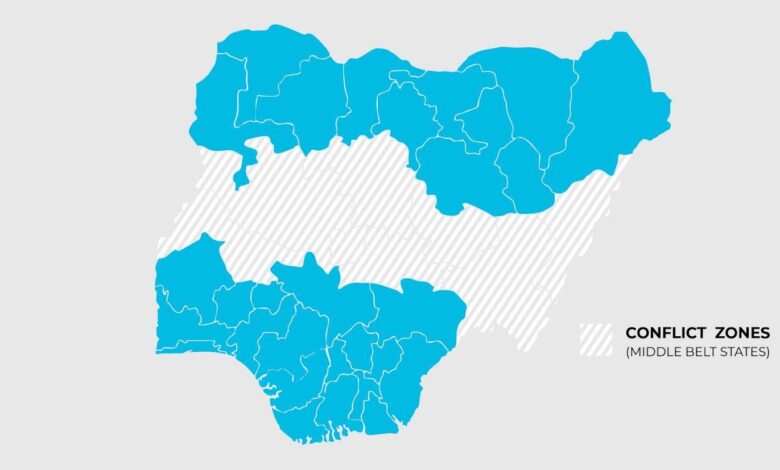

For decades, the farmer-herder crisis has ravaged North-central Nigeria, killing over 60,000 people and displacing hundreds of thousands, according to local authorities. Benue and Plateau States have endured the worst of the relentless bloodshed of one of the country’s most severe security threats.

Historians trace the roots of the farmer-herder conflict in the region back to the early 1900s, but its intensity has escalated dramatically in the past two decades. Some experts attribute this escalation to environmental pressures forcing nomadic herders, predominantly from the far north, to migrate southward in search of resources such as grazing land and water.

“The animosity stems from competition over land and resources, worsened by climate change, population growth, and desertification in the north driving herders southward,” Dominic Aondowase, a conflict and international security researcher at the Nigerian Defence Academy, Kaduna, told HumAngle.

As herders move south, the absence of clear land tenure policies and grazing reserves often leads to the encroachment on local farmlands, deepening tensions in the Middle Belt areas, including Benue, Plateau, Kogi, Kwara, Nasarawa, Niger, Taraba, and the Federal Capital Territory.

“Longstanding grievances over unequal access to resources, political exclusion, and systemic neglect by the government contribute to resentment among both groups,” Aondowase added. “Farmers feel displaced by encroaching herders, while herders perceive anti-grazing legislations and restrictions as discriminatory.”

The Miyeti Allah Cattle Breeders Association of Nigeria (MACBAN), an umbrella body for most herders, has staunchly opposed legislation banning open grazing. MACBAN described anti-grazing laws as “an attempt to criminalise our means of livelihood of cattle-rearing through satanic and obnoxious laws.”

Local authorities, however, remain resolute. The Benue State government has vigorously defended its anti-grazing law, arguing that armed herders are responsible for the violence that has claimed lives, displaced communities, and plunged the state into a humanitarian crisis.

In July 2024, the Benue Livestock Guards, tasked with enforcing the anti-grazing law, impounded cattle openly grazing in Makurdi, the state capital. Later that day, armed men allegedly launched an attack on members of the Livestock Guards, said Joseph Har, Special Adviser to the Benue State Governor on Internal Security.

“These incidents reinforce Benue’s commitment to the anti-grazing ban,” Har stated.

Gideon Para-Mallam, President and CEO of The Para-Mallam Peace Foundation, a non-governmental organisation advocating for peace in the region, argued that enforcing anti-grazing laws without exacerbating tensions requires a thorough and transparent approach predicated on fairness and justice. He, therefore, urged the government to ensure that all lands are registered and documented both at the local and state government levels.

For ethnicity and religion?

Meanwhile, not all experts agree that the crisis is purely a competition for resources. One of them is Zariya Yusuf, former National Coordinator of Middle Belt Patriots, an advocacy group in the region. He argued that the violence is more organised than it appears to be.

“It would be easier to dissect if these were simply two groups clashing. There is a jihadi group—an Islamist militia—leaving hundreds of Christian corpses in its wake after attacks across the Middle Belt,” he said. Claims like Yusuf’s introduce an ethno-religious dimension to the conflict, further complicating the narrative.

Ethnic and religious tensions have long been a source of conflict in the region, particularly between “indigenes” and “settlers”. While many indigenous people of the Middle Belt states are Christians, the herders are predominantly Muslim.

In September 2001, for instance, locals in Plateau State fiercely opposed the appointment of Mukhtar Muhammad, a “settler”, as the poverty eradication coordinator in Jos North. The situation escalated after the circulation of anonymous leaflets warning that Sharia law would soon be extended to the state.

The ensuing riots caused immense suffering, claiming thousands of lives, displacing countless people, and destroying property on a massive scale. Similar incidents had occurred at least three times in Plateau State in the late 1990s, including one triggered by the appointment of a Muslim as the sole administrator of Jos North Local Government Area.

The sacred truth, however, is that both sides—local Christians and Muslim herders—have repeatedly suffered human and material losses over the years and have equally been engaged in targeted attacks on one another.

A cycle of reprisals

Yusuf contends that injustice and the absence of accountability for past crimes perpetuate the cycle of reprisals in the Middle Belt. “There are, indeed, historical grievances and perceptions,” he said. “These issues are deeply rooted in the pre-colonial Jihad wars and the colonial administrative style, which left the Middle Belt peoples feeling oppressed, suppressed, and alienated even in their own homes.”

The violence often spirals into retaliatory attacks, as seen in August 2021 when 26 travellers returning from an Islamic event were killed by hoodlums along Rukuba Road in Jos North, Plateau State. This area, predominantly inhabited by the local Irigwe people, erupted into riots following the incident, prompting the government to impose a curfew across the Jos-Bukuru metropolis.

Locals told HumAngle that the killings were a reprisal for attacks on local farmers in Miango District, an Irigwe community, allegedly carried out by armed herders, who claimed that their cattle were rustled. In some instances, the assailants left inscriptions such as “No more Irigwe in Nigeria” on the walls of houses, further deepening tensions. This is just one of many reprisals between the groups in the region.

A series of HumAngle investigations in the past revealed that violence during Christmas 2023 in the Bokkos and Mangu areas of Plateau State followed a similar pattern. Armed assailants, reportedly of Fulani descent based on their use of Fulfulde language, attacked and killed Panmun Isa, a local farmer in Bokkos, along with some of his family members.

Isa’s farmland was located in a community where Mwaghavul locals had previously displaced Fulani settlers, who are mostly herders, after a land dispute. The attackers allegedly targeted Isa as retribution for participating in their displacement. The timing of the attack, during Christmas—an important religious celebration for Christians—further inflamed tensions, triggering a cascade of reprisals that claimed numerous lives and displaced hundreds.

There’s more

While incidents like Isa’s death can spark violence, cattle rustling by local communities is another significant trigger. Some herders argue that these issues are frequently underreported, with narratives often skewed toward local communities. “Most of the problems are happening when our people resist any attempt at rustling their cattle,” according to Garba Abdullahi, the Plateau Chapter chairman of Gan Allah Fulani Development Association of Nigeria.

“Cultural practices and communal identities tied to land and livestock create rigid fault lines,” Aondowase said. “The crisis is also influenced by external actors, including armed groups exploiting local vulnerabilities for personal or ideological gains.”

On his part, Plateau State’s Information Commissioner Musa Ashoms, highlights “personal gains” as a driver of the conflict, as he linked recent violence in Mangu and Bokkos to land-grabbing. “It is land grabbing, it is ethnic cleansing,” Ashoms said. “The assailants are after land. We have been reliably informed there are valuable minerals there. They kill people, drive them away, and take over their land.”

Beyond land disputes and resource control, weak governance, inconsistent security responses, and the absence of a functional judicial system have further aggravated the crisis and forced many to resort to vigilante actions to settle disputes. For instance, during the July 2021 attacks in Miango, locals alleged that security personnel on the scene refused to engage the assailants, citing a lack of orders to do so.

In a recent interview, Plateau State Governor Caleb Mutfwang said that fifth columnists have infiltrated the security agencies, explaining that some personnel have even compromised their colleagues. However, security authorities have consistently denied these allegations of inconsistent security responses, citing logistical challenges, particularly in rural areas with poor road networks, as a major setback.

“Most times, attacks—like the one during the 2023 Christmas—happen simultaneously, making it difficult for our men to respond effectively,” an army officer, who requested anonymity due to restrictions on speaking to the press, told HumAngle.

Will there be peace?

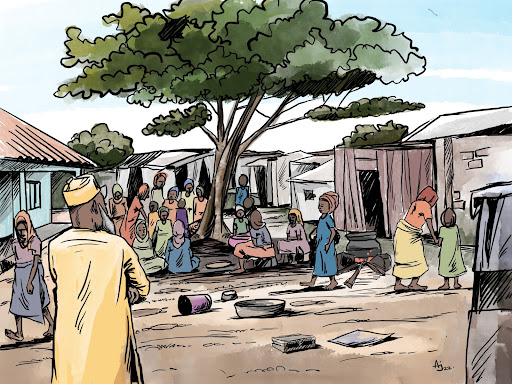

Over the years, numerous peacebuilding initiatives by state authorities and non-state actors, including faith-based organisations, have sought to address the crisis in the region. Yet, the conflict persists despite these sustained efforts.

In Plateau State alone, over 40 organised peacebuilding actors are active, according to the Plateau Peace Building Agency. However, “the lack of inclusive frameworks prevents sustainable conflict resolution,” Aondowase argued.

While Para-Mallam acknowledged that peacebuilding initiatives in the Middle Belt have been encouraging, he argued that efforts have largely been focused on conflict resolution, rather than prevention or mitigation, which should seek to end violence.

“There’s a need to shift focus from cosmetic approaches of conflict resolution to the social surgical concept of conflict transformation,” Para-Mallam said. “Conflict transformation requires truth-telling and accountability from both the people and their government. This could lead to socio-economic development aimed at transforming the conflictual context, leading to healing and reconciliation, which are prerequisites for sustainable peace.”

He, therefore, urged a comprehensive overhaul of the current land administration system, which he said exacerbates conflict rather than reduces it. “Land grabbing is a recipe for a breakdown of law and order,” he said. “Clearing all ambiguity in the legal framework establishing land rights will ensure a new regime that defines land ownership and usage. The government should make it criminal for anyone to grab land by force of arms.”

Meanwhile, Yusuf pointed to justice as the missing ingredient for sustainable peace. “Peace has never been established where justice has not been effected. It is not so much of a lack of “peacebuilding initiatives” but the failure to dispense justice,” he argued. “How do you midwife peace between any two groups when one is dislodged from their ancestral home and their community is currently occupied by those they are expected to enter peace with?”

The farmer-herder conflict in North-central Nigeria has led to over 60,000 deaths and widespread displacement, predominantly affecting Benue and Plateau states. The conflict, rooted in historical competition over land, has intensified due to environmental factors like climate change and desertification forcing herders southwards. Clear land policies are lacking, leading to encroachment on farmland and exacerbating tensions. Ethnic and religious dimensions fuel the conflict with both groups suffering losses.

Efforts to resolve the crisis face challenges such as inadequate governance, land-grabbing, and ineffective peacebuilding initiatives. Local authorities have attempted to curb violence with anti-grazing laws met by herder opposition.

For sustainable peace, experts recommend transparent land administration and justice for displaced communities, focusing on conflict transformation rather than temporary resolutions.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter