Seven Years On, Blood From Giwa Barracks Massacre Yet To Dry

The Giwa Barracks massacre left a trail of injustice for the victims and a damaging aftermath on those who survived. Seven years later, the Nigerian government remains silent on the incident.

When her young boy was picked up by the Nigerian military nearly a decade ago, Ya Amsa Fannami was advised to give up trying to look for him because “these people would kill both you and your son.” Bana Usman, only 17 at the time, was arrested close to the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital in Borno state’s capital city. He was a student at Shehu Sanda Kyarimi Secondary School.

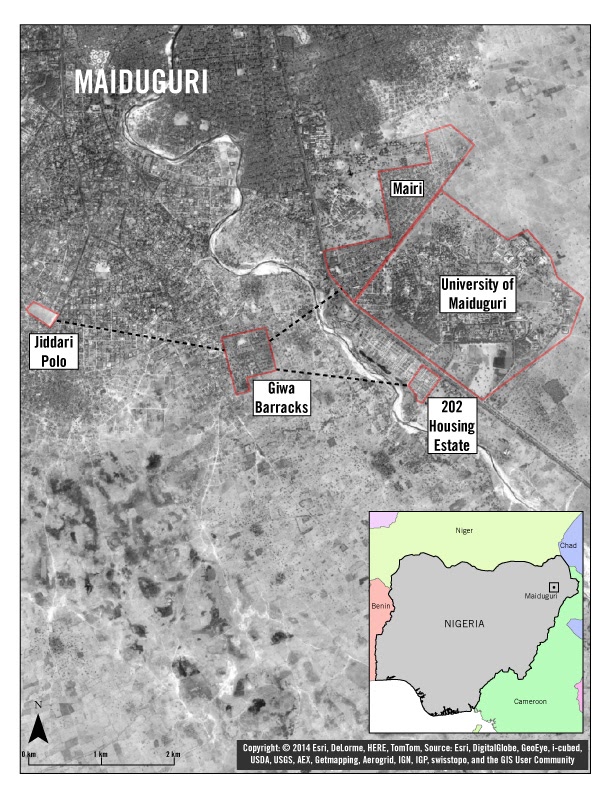

After a frantic search, she later found out he had been taken to the Giwa military detention centre located in the outskirts of Maiduguri. For almost five years, she did not hear a word about Bana. And then, in the early hours of Friday, March 14, 2014, Boko Haram insurgents led by Mustapha Chadi, one of the terror group’s commanders, stormed the detention centre and staged a daring jailbreak.

Military detention facilities in areas ravaged by the Boko Haram insurgency often indefinitely hold people suspected to be members, allies, or sympathisers of the terror group. Many were arrested arbitrarily during mass arrests in Maiduguri or after their communities, formerly seized by Boko Haram, were recaptured by the Nigerian Army. So, it is common to find detainees with no affiliation whatsoever to the terror group.

Following the jailbreak, several detainees followed the insurgents back to their camps in the forest areas. Some, who would have joined, could not because of the limited number of trucks. In the ensuing chaos, dozens of other detainees scampered in the direction of Maiduguri, hoping to escape to freedom — or anything at all. Instead, they ran into a savage mob of civilians, the paramilitary Civilian Joint Task Force, and soldiers.

Though the escapees were unarmed, they were indiscriminately murdered — shot at close range, swiftly slaughtered or gradually butchered — and buried hurriedly. HumAngle noted from videos of the carnage that some were forced to dig their graves before they were laid down and had their throats slit with crude machetes. As many as 20 or more former detainees could share a single grave.

Amnesty International located three possible mass graves in the city using satellite imagery and estimated that the Army killed about 640 men and boys, but eyewitnesses put the figure even higher.

“The lack of an independent investigation has meant that no one has been held to account for the killings, strengthening an already pervasive culture of impunity within the military,” the advocacy group said in 2016. Five years later, observations about the massacre and requests for justice are still met with dead silence from the authorities.

Yet, the wounds inflicted on that day remain fresh. Fannami’s family is one of countless that have been permanently scarred.

Hearing about the jailbreak, she had embarked on another search for her young boy. She went to Jiddari Polo, Modu Ganari, and other places where former detainees were killed and saw about 50 corpses. But Bana was not among them, so she gave up and returned home.

Then Bana’s sister heard on the radio that some people were taken to the hospital after the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) intervened. She visited the hospital and met her brother in a terrible condition. He had become significantly darker. He could not speak. He could not sit up. And three of his fingers had been severed.

“We spent three months in the hospital looking after him,” Fannami recently told HumAngle. “He later got better, but he became mentally sick. So we took him to a psychiatric hospital and stayed there for one month and came back. He is still mentally sick now.”

She said representatives of the National Human Rights Commission visited their house and promised to urge the government to take responsibility for Bana’s treatment. That was two years ago. Nothing has since been done to fulfil that promise.

“His condition is very bad. He can’t even wear trousers and a shirt. If it is possible, let them take us to someone that would treat him,” she said.

“We went to Abuja and suffered. He was walking, a very smart boy. He was a complete person. But they chopped his fingers and made him useless. He throws stones at people and often causes problems with our neighbours. If I am not around, my small girl will clean and bathe him. Even eating food, he doesn’t know; we have to feed him.”

Bana is incapable of basic tasks. He urinates in the open and sometimes hurls faeces at co-tenants and passers-by, causing neighbours to isolate the family and treat them with contempt. Fannami hopes the government will either ensure her son’s full recovery or provide safer accommodation for them.

A report published by Amnesty International in 2015 suggests that the Nigerian military got wind of the jailbreak before it was executed, as soldiers were said to have evacuated their families from Giwa barracks.

“On that Thursday, soldiers packed their properties and removed their wives and children. In the evening, they removed their armoured tankers. Only three soldiers were left,” 31-year-old Kallo, a former detainee, informed the organisation.

“The Boko Haram came in the morning and told us to follow them and take weapons. I said, ‘no, I don’t know how to shoot, and I haven’t seen my father or mother for almost two years, so I cannot join you.’ They loaded the weapons on their vehicles.”

The inmates said they were offered a choice by Boko Haram to either join their ranks or return home. Many opted for the latter option.

When they got to Maiduguri, some of the city’s residents started to help them by providing them with clothes, food, water, and a place to hide. But they could not sustain this approach as soldiers and CJTF members went on a hunt for the escapees from about 9 a.m.

“They conducted house-to-house searches and threatened to arrest any resident who was hiding a former detainee. Many residents told Amnesty International that they felt that they had no choice but to hand over detainees sheltering in their homes. Most rearrested detainees were extrajudicially executed by soldiers that day, in some cases with the help of Civilian JTF members,” Amnesty International reported.

One resident recounted seeing young boys scampering for safety as soldiers and paramilitary officers picked them up one after another.

“Later, they took them to the side of the town and gathered them. Then the soldiers came and gathered them in one place; they were so many. They held a meeting and resolved to kill them; then they killed all of them with their guns, one by one,” he told HumAngle.

“There were many of us that witnessed that when it happened. Some people said they are Boko Haram and others said they were people from another area. We were not sure about anything. There was one boy we know who used to be a health worker who was among them, but we were sure he was not a Boko Haram.”

Another witness remembers witnessing a scene where a young boy from Jiddari pleaded to be spared, assuring the assailants that he was not a Boko Haram member.

“The boy was saying to the people, ‘Can’t you tell them I am not Boko Haram?’ But we were looking at them from afar. We were looking at everything when they finished all of them. It was about two days later that they came and took them away,” he said.

“There is no issue of justice. They were not taken to court, so there is no issue of justice. Everyone was afraid because they could even arrest you in your house and say you are Boko Haram. No one could talk about it. That was what happened.”

HumAngle has seen dozens of videos where security forces, joined by some residents, and members of the CJTF, chased down fleeing detainees. The corpses of these detainees that littered the city of Maiduguri were taken to the mortuary; others were dumped around the Giwa barracks vicinity and buried in mass graves.

Some residents could identify their loved ones before or after they were executed, but were too afraid to say a word because of the vicious mob.

It has been seven years since the massacre happened and there is still no justice in sight, either for the dead or the living. Many families that had hinged their hopes on the presidential panel investigating the massacre now have their hopes dashed. There is grave silence about the panel’s findings though it submitted its report to the presidency nearly four years ago.

Additional reporting by Fatima Bukar and Yakura Kumshe.

This investigative report is a partnership between the African Transitional Justice Legacy Fund and HumAngle Media under the ‘Mediating Transitional Justice Efforts in North-East’ project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter