Secrets, Silence, Survival: Inside a Nigerian Military Prison

In Wawa, a prison in North Central Nigeria run by the Nigerian Army, terrorists and civilians occupy the same cells, held incommunicado under what they describe as some of the most terrible conditions.

No one recalls the road to Wawa. New detainees are blindfolded several kilometres ahead. Inmates are also blindfolded and driven out before release.

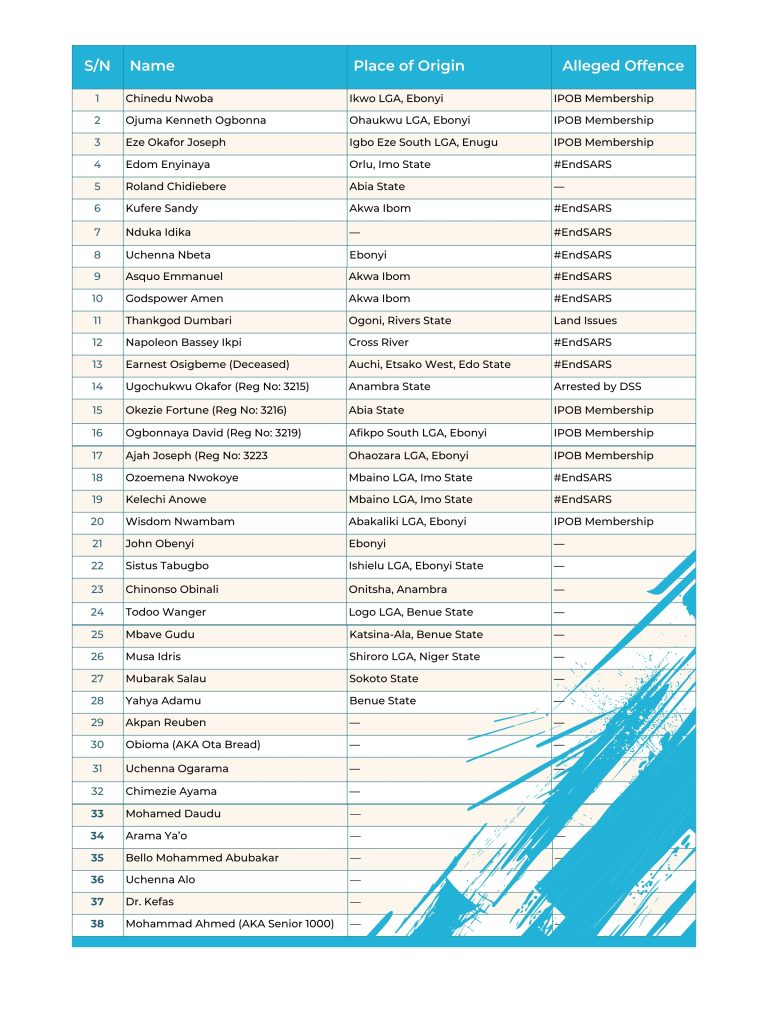

It was July 27, 2021. Eleven people returning to South East Nigeria after the trial of Nnamdi Kanu, leader of the separatist group Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), at the Federal High Court, Abuja, were intercepted by the Department of State Services (DSS) along Lokoja. (IPOB has been fighting to secede the southeastern region to the independent nation of Biafra.) Labelled members of IPOB’s armed wing, known as Eastern Security Network, the travellers were taken into a dark, underground DSS cell in Abuja. A few weeks later, they were paired out before daybreak and chained ahead of a “military investigation.”

Nonso and Pius Awoke landed in the Wawa prison, a military detention facility in North Central Nigeria.

Nonso, in his final year, was studying computer science at the Ebonyi State University, and Pius practised law in the same state. On the night they arrived in prison, they said, they were first stripped by soldiers and beaten with cables. Nonso got the registration number 3220, and Pius, 3218.

Located in Niger State, the Wawa prison complex is shrouded in mystery. Except for an October 22 attack by the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), almost nothing is public about it. Even the specific location of its housing facility, the Wawa Cantonment, is a subject of disagreement. Some reports trace it to Wawa town, others say it’s in Kainji or New Bussa, which, though geographically related, are different communities in the state.

HumAngle combined Open-Source Intelligence and satellite imagery to locate it. It is situated along the Kainji-Wawa highway, roughly 3 – 4 km east of Wawa town and another 3 –4 km west of the Nigerian Air Force Base in New Bussa. It is accessible from both towns within 4 to 6 minutes by vehicle, depending on road conditions.

Far left into the sizable military installation on Wawa-Wakwa Road, between Wawa town and Tamanai village in the Borgu Local Government Area (LGA), is a collection of buildings that closely match the description of two sources. The nine two-storey blocks separated by double walls are the prison complex, designated ‘A’ to ‘I’.

“Each floor contains 10 cells,” Pius said. “In every cell, there are 15 inmates, making approximately 450 per block.”

The military prison primarily holds suspected members of Boko Haram, which has terrorised Northern Nigeria for 16 years and killed at least 20,000 people. In 2017, a court set up in the cantonment tried 1669 suspects behind closed doors, convicted some and awarded prison terms ranging from three to 60 years. ISWAP’s attack on the facility later was to liberate their incarcerated members, but they lost eight more men instead, including a commander, to a joint force of local vigilantes and soldiers.

United by fate

The largest groups in Wawa are tied to terrorism in the north, militancy in the middle belt, and secession threats in the South East. Most of the Igbo inmates were picked up after the nationwide #EndSARS protests of October 2020, sources said. During the protest, which started as a peaceful demonstration against police brutality, there were reports of IPOB-sponsored attacks on security personnel in Obigbo, Rivers State, which led to the declaration of a curfew and the invitation of the military by the then-governor Nyesom Wike. The soldiers, however, embarked on door-to-door raids, torture, rape, executions, arbitrary arrests, and disappearances of locals, especially men.

“Thirty-four of them were taken to Wawa,” said Nonso. “Some of them were conductors and drivers going about their businesses. One of them was arrested for having a tattoo. They said he was an unknown gunman. One was even arrested for having a beard. One of my brothers from Rivers State, his offence was that he greeted a soldier.”

The rest came from Anambra and other southeastern states. Emeka Umeagbasi, whose organisation, Intersociety, sent an undercover agent to Wawa while compiling a report in 2024, confirmed this.

“In our recent report, there’s a declassified document showing a request by the Nigerian Army for the transfer of so-called Boko Haram and IPOB terrorist suspects from the police headquarters to Wawa Military Cantonment,” he told HumAngle. “What else is more evidential?”

The events that culminated in the incarceration of a large number of Tivs in Wawa began with a peace meeting in the Katsina-Ala LGA of Benue State on July 29, 2020. Politicians, chiefs, and religious leaders gathered in Tor-Donga, the Tiv people’s capital, to settle years of “armed robbery, kidnapping, murder, rape, and other criminal acts” connected to Terwase Akwaza, also known as Gana, a notorious militia leader who had been in hiding. The team requested amnesty for Gana and his gang members and offered an apology to Samuel Ortom, the governor at the time.

Though a known criminal, Gana was also a messiah in Sankera, the senatorial district covering Katsina-Ala, Logo, and Ukum LGAs. When the federal government appeared to be ignoring deadly armed herder incursions, it was Gana and his men who protected the people and their vibrant agricultural economy. Sankera, the location of Zaki Biam, the world’s biggest yam market, accounts for 70 per cent of Nigeria’s annual yam production.

“Gana was employed by community leaders to defend the people against herders,” Jeremiah John*, a Sankera native, told HumAngle.

The militia leader bowed to pressure from traditional authority after the Tor-Donga summit. On September 8, 2020, he and his gang members publicly gave up their weapons and joined a convoy heading to Makurdi, the state capital, to conclude a peace deal with the governor. The military, however, intercepted the convoy, which included clergymen and community leaders, and took Gana and his gang members. News of his death would spread a few hours later.

In a picture of his dead body later circulated on social media and seen by HumAngle, his body was bullet-ridden, and his right arm had been severed from his body.

On Facebook, HumAngle saw a petition addressed to the National Human Rights Commission in November 2020, seeking the release of 76 surrendered militants arrested with Gana. Tor Gowon Yaro, the Benue State native who signed the petition, told HumAngle that the men were still in military detention.

“None of them has been released,” he said. “None that I’m aware of.”

Suspected terrorists are the largest single group in Wawa. About a decade ago, Boko Haram took over communities in the Banki axis of Borno State and held residents hostage. Upon a counter-operation by the military, the terrorists fled. However, soldiers claimed that the villagers were complicit and drove hundreds of them to the Bama IDP Camp, where they separated the men and took them to military detention. This happened in several other villages, and residents who also tried to escape their terrorised villages to Maiduguri, the capital city, were often intercepted and detained.

“Half of Borno youths, especially the Kanuris, are in detention,” Pius cried.

Other demographics in the facility are Fulani men detained over kidnapping, underage boys, and even some mentally-challenged people arrested in Maiduguri and accused of being Boko Haram members, sources said.

HumAngle has extensively documented this arbitrary detention problem in Borno, involving thousands of men who have been detained for about a decade now, prompting their female relatives to form the Knifar Movement to advocate for their release. Though they are periodically released in batches, many are still in detention. HumAngle has confirmed the release of at least 1009 men from the Wawa prison and the infamous Giwa barracks in Maiduguri.

Behind the prison walls

“Once you’re inside, you’re inside,” said Onyibe Nonso, an undergraduate who spent nearly three years in the facility. The cell door quickly shuts after letting in food, and the special day when inmates step out for sunning may not come in a whole year. To survive, you must first accept every cellmate, no matter their tendency or ideology, including terrorists and mentally ill people.

Every day is a routine, Pius said – wake up, pray, sit down. Sometimes, you gist with fellow inmates. Other times, cellmates play the Ludo board game among themselves. Some cells have Hausa literature supplied by the Red Cross, where one could read. Since no single meal in the facility can satisfy an adult, many have formed the habit of fasting every day until evening, when they combine the meals and drink the little water available.

“If they gave us beans, you would not see a single seed, only water,” said Pius. He also recalled having no water to bathe for a whole month.

The toilet and bathroom carved out of each cell, the same cell that is smaller than the average bedroom and still accommodates belongings like jerricans, has no door.

“We shared the rest of the space,” said Nonso. “To sleep, each person would place their blanket on top of their mat and leave a small space in-between.”

You stand and sit in your small portion. On the evenings when inmates squabble over space, they quickly resolve before soldiers return in the morning. It must not escalate lest they all suffer the following day.

Conditions generally improve when the Red Cross visits, but soldiers assure inmates of a return to the old ways.

“And truly, things would return,” said Pius. “For over a year before I was released, the Red Cross did not come. We heard that it was because the military authorities mismanaged the things they brought.”

An information blackout tops Wawa’s many woes, according to Pius.

“I didn’t know they changed money,” he said, referring to the time when Nigeria redesigned the naira note. “I didn’t know whether a relative was dead or not. We didn’t know Tinubu was running. We didn’t know who was going to be sworn in – just like I was completely excommunicated.”

Back home, families were struggling to move on. When Nonso’s mother heard his voice for the first time in three years, she called back to make sure it wasn’t just another fantasy. It was on June 21, 2024, the day he was released. After two months in the hospital, 20 bags of drips and a lot of prayer, she was already making peace with her only son’s death.

And death is truly cheap in the military prison. From beatings, starvation, and complications arising from inadequate healthcare, inmates die randomly. When the undercover agent from Intersociety arrived at the facility in September 2024, at least 10 inmates had just died within the week.

“A Muslim lieutenant colonel from the north, who provided us with 10 names of people who had just died in the detention that week, told our undercover, ‘Look at how your people are dying here,’” Umeagbasi told HumAngle.

Nonso saw at least two dead bodies himself. Despite being rarely allowed to speak with inmates from other cells, Pius knew of at least 10 deaths. Earnest, one of those brought in from Port Harcourt shortly after the #EndSARS protests, died of complications related to diabetes.

“I know him in person,” Pius told me. “We met one day.”

The more inmates die, the more new ones arrive. The total number, which Pius said matched his registration number on arrival, had climbed to over 5000 by his release in June 2024. As the number grows, so does the intensity of abuse.

“Some of those who got there before us said there was no such thing as beatings when they were brought in. We met it during our own time, and those who came after us had even tougher experiences. They sustained serious injuries and weren’t given adequate treatment,” Nonso said. An inmate who was released from the prison last year after 11 years in detention had an account similar to this. She told HumAngle that though the physical abuse was intense at the beginning of her stay there, it stopped at some point. Shortly before she was released, however, it resumed.

Many of the Tiv inmates arrested alongside Gana couldn’t survive the abuse they were subjected to, Pius revealed. “They beat them in a way that when they got to that detention [Wawa], most of them died.”

Until their release over media pressure and advocacy efforts by the Nigerian Bar Association, neither Nonso nor Pius set foot in court, raising questions about why they were arrested in the first place.

The Red Cross and the Nigerian Army have not responded to inquiries sent to them.

*Jeremiah John is a pseudonym we have used to protect the source’s identity.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Pius Awoke practised law in Akwa Ibom.

A group of detainees, largely considered political prisoners, are held under dire conditions in Nigeria's secretive Wawa military prison, infamous for its harsh treatment and obscure location. Several detainees, including members of IPOB and alleged Boko Haram affiliates, face physical abuse, lack of basic necessities like adequate food and water, and are cut off from news or contact with the outside world. Deaths are common, resulting from beatings and inadequate medical care. Many detainees await release without trial, highlighting the secrecy and injustices surrounding their incarceration. Despite these challenges, advocacy efforts by organizations like the Intersociety and media attention have resulted in some releases.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter

The military jailers are equally in jail. No one is truly free. Our society is living a lie. The more we encourage societal dis-functionality, the less likely for insecurity to be resolved.

The future holds more dangerous events and we must brave up for them.