In hundreds of their books, pamphlets, and other propaganda materials, Jihadists quote several medieval and contemporary Muslim scholars in attempts to justify waging violence on others. But one name stands out: Ahmad Ibn Taymiyyah.

Ibn Taymiyyah was a 14th-century Syria-born puritan theologian and jurist who wrote hundreds of volumes on various Islamic topics, including his contentious fatwas on jihad and takfir. He was most active in his anti-Mongol and anti-Nusayri (now Alawites) polemics, in which he wrote three notable fatwas, all named Mardin Fatwas. These rulings are still used today by Jihadists to justify takfir on (denouncing) Muslim rulers, as Ibn Taymiyyah himself did on Mongol (Tatars), Nusayri Shiites, and other Muslims he labelled apostates.

Ibn Taimiyya made Mardin Fatwas precisely in the historical context of the Mongols’ attempts to conquer Syria following the fall of Baghdad in 1312. He issued the religious rulings to address the dilemma he and some Syrians were experiencing as a result of the Mongols’ aggressions though they had already converted to Islam. By offering fatwas that could camp the Mongols alongside other “enemies” such as “Kuffar” (infidels) and “bughat” (rebels), he tried to justify taking up arms against them though the Mongol force was a mix of Muslims and non-Muslims.

Ibn Taymiyyah’s works have been widely cited by Boko Haram, a terror group that sprang up in northeastern Nigeria. He has been featured by the group’s founder, Muhammad Yusuf, in his publications, including the most popular one, Hazihi Aqidatuna. Abubakar Shekau, Yusuf’s successor and Boko Haram’s late leader, has also mentioned him many times in his speeches.

The Islamic State (IS), its affiliates, and Al-Qaeda groups have equally released publications basing their arguments on Ibn Taymiyyah. He was quoted not only on jihadi issues but also on various other topics of theology. As divisions among the Jihadists continue to sour, they also quote other texts by Ibn Taymiyyah to justify attacks on one another.

In their attempts to distance themselves from the Jihadists while also using Ibn Taymiyyah’s texts, mainstream Salafists (advocates of purist interpretations of Islam) have argued that he should be read with a historical context. They say that his anti-Mongol fatwas were peculiar to his time and his circumstances. While mainstream Salafists believe his fatwas were defensive against external aggression, Jihadists believe they were offensive because the Mongols converted to Islam but did not practise Shari’a (Islamic law).

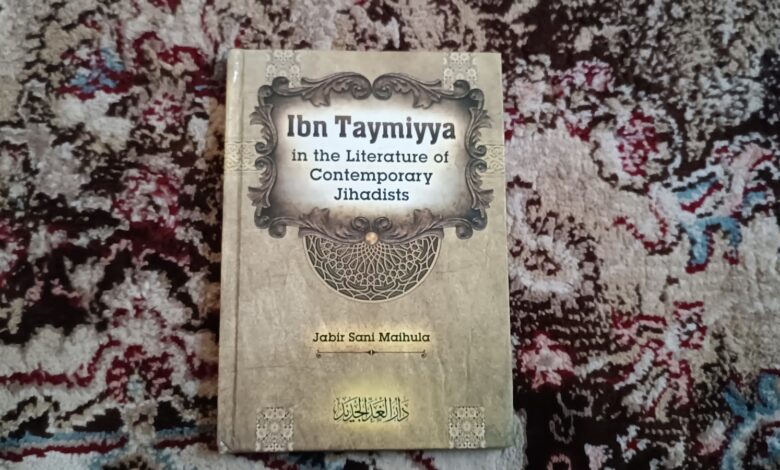

It is in this struggle to reclaim Ibn Taymiyyah that Jabir Sani Maihula, a Nigerian Salafi preacher, published “Ibn Taymiyyah in the Literature of Contemporary Jihadists,” arguing, like many other writers before him, that Jihadists misquote or misapply Ibn Taymiyyah’s rulings. The book responds to the Jihadists’ attempts to use Ibn Taymiyyah’s works as a justification for violent campaigns. The book is less than a hundred pages long and offers an “Ibn Taymiyyah hermeneutic that differs from Jihadists”.

Maihula argues that Jihadists are cherry-picking Ibn Taymiyyah’s works and ignoring their contextual application to justify their prior decision to join violent Jihad.

The book analyses two works, Alfaridha Alga’ibah and Al-Umda Fi i’dad Al’udda, written by Egyptian jihadi ideologues Abdus Salam Alfaraj and Abdulqadir Abdulaziz, to provide a detailed historical evolution of how pre-Al-Qaeda Jihadists began relying on Ibn Taymiyyah as a source of inspiration since early 1980.

The author observed that Alfaridha Alga’ibah was the first radical interpretation of Ibn Taymiyyah’s works. The other book, according to him, has shown how not only Ibn Taymiyyah’s works but also the works of other classical scholars were used to justify a violent jihad campaign.

The second chapter examines references to Ibn Taymiyyah in Al-Qaeda, IS, and Boko Haram literature, particularly in their magazines: Dabiq, Madad, and Inspire. Following his analysis, the writer argued that Salafi-Jihadists “analogise the contemporary period with the period of the Mongol invasion of Syria and thus divide people into three groups following Ibn Taymiyyah’s division of people into three groups with respect to the Mongol invasion of Syria.”

The jihadi filters

Salafi-Jihadists and mainstream Salafists share some canonical sources. However, they have been engaged in a heated intellectual debate over who has the authority to interpret the sources. Ibn Taymiyyah was a father figure to both of them, and various Salafist mosques and centres, including that of Boko Haram in Maiduguri, were named after him.

However, as Alexander Thurston argued, while Salafists share some sources, they interpret medieval traditions differently, such as the one produced by Ibn Taymiyyah. The terms in the texts may be the same, but their interpretations differ depending on the ladders climbed by different readers.

“Even when a Salafi today drenches himself or herself in a vocabulary that is directly borrowed from Ibn Taymiyyah and other medieval scholars — describing himself or herself with terms like Ahlussunnah Wal Jama’a — he or she employs understanding of these terms that has been filtered through various intermediaries,” Thurston writes in his Salafism in Nigeria.

This explains why different Salafi groups have different interpretations of the same Ibn Taymiyyah text. While mainstream Salafists mostly rely on the works of contemporary scholars like Nasiruddeen Albani, Ibn Bazz, and similar Salafi scholars to understand classical texts, Jihadists have their own scholars, including Abu Muhammad Al-Maqdisi, a Jordanian Salafi-Jihadi ideologue.

Maihula contended that Ibn Taymiyyah advocated a defensive jihad, as opposed to the offensive jihad advocated by contemporary Jihadists. He also observed that Ibn Taymiyyah stated that only fighters should be killed in jihad, and that it must be waged under the supervision of a leader.

“In the anti-Mongol fatwas, his [Ibn Taymiyyah’s] harsh approach to the Mongols due to the practical danger he and Damascenes faced subjected his fatwas to be hijacked by the Jihadists,” the author wrote.

Context and limitation

The book has touched on some important questions surrounding the presence of Ibn Taymiyyah in jihadi literature. However, due to its small size, it lacks details and is unable to deeply explore some of the questions asked by researchers trying to find distant roots of Islamist and Jihadi terrorism.

While the author attempted to distance Ibn Taymiyyah from Jihadist works, describing it as the misappropriation of fatwas, he was unable to explain why Ibn Taymiyyah dominates Jihadist literature more than any other scholar who equally wrote on jihad and other doctrinal issues. Classical scholars, such as Ibn Hazam and Ibn Hanbal, are found in Jihadi literature but not at the same level as Ibn Taymiyyah.

One could argue that the main difference between Ibn Taimiyya and other writers on Jihad is that they lived in a peaceful period, whereas Ibn Taimiyya lived in a period of crisis. Like Sayyed Qutb, who witnessed the gradual fall of Arab countries and was radicalised into producing radical texts while imprisoned, Ibn Taymiyyah lived during the time of Mongol conquest and was similarly imprisoned for his extreme religious views.

The writer was able to portray that people with different ideological stances could read the same text by Ibn Taymiyyah and apply them in variance. For the author, a parallel exists between the era of the Mongol Empire, in which Ibn Taymiyyah lived, and the contemporary world. However, for Jihadists, the fatwas are timeless with no contextual consideration.

Whether read in or out of context, Ibn Taymiyyah’s influence on jihadi activities is clear. While Maihula stated that Ibn Taymiyyah justified suicide, Jihadists have taken that and expanded it to include attacks on both Muslims and non-Muslims. Maihula could argue that the suicide mission can only be legitimised in a “true jihad”. And the Jihadists would reply that their call to arms is legitimate.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter