Recent Homicides in Kano Reveal Gaps in Community Watch and Early Warning Systems

A recent series of brutal daylight murders in the Kano metropolis, northwestern Nigeria, reveals how fading communal vigilance is leaving even close-knit neighbourhoods dangerously exposed to violence.

What Bashir Haruna would later remember was only the ordinariness of that cold morning.

He had prepared to go out early, and the day had not announced itself as a tragedy. His wife, Fatima Abubakar, was quietly arranging the clothes she planned to wash while he stood watching her. There was no hurry, no sense of foreboding. He later heated some water and took his bath.

When he finished getting ready, he wheeled his motorcycle and rolled it towards the door. As she always did, she followed him. He smiled and asked, half-jokingly, “Won’t you escort me further?”

“I wish you a safe return,” she replied.

It was the last sentence she would ever speak to him.

What followed exposed not just a crime, but the dangerous silence of a community that did not hear or respond in time.

The murders of Fatima and her six children in Dorayi-Chiranchi, a neighbourhood in Kano, northwestern Nigeria, occurred just weeks after the killing of two housewives in Tudun Yola, another community in the city. Both incidents happened in broad daylight, inside residential neighbourhoods where neighbours, guards, and passersby were close enough to hear but not close enough to stop the violence.

Together, the cases reveal a breakdown of community vigilance in a city once defined by collective watchfulness.

Bashir returned home to find his wife and his six children lying motionless, soaked in blood. None could tell him the horror they had witnessed. He was unprepared for such violence. He had never imagined losing his family in such a brutal way.

This is what happened.

At around 11 a.m. on Saturday, Jan. 17, the man accused of the crime, Umar Auwal, and two other suspects arrived at the house. He knocked. Fatima asked who it was, and he answered. There was no suspicion. No reason for fear. She opened the door to someone she believed was safe, Umar, described in a police report as her nephew.

What followed remains largely unknown. There were only guesses and the gaps of silence that violence always leaves behind. But the screams broke through that silence.

“Umar, please do not kill me,” a voice cried.

It was the children in the neighbourhood who heard it first. Nearby youths had turned up a radio, and according to the eyewitnesses, the sound carried oddly, distorting the cry. They did not immediately recognise it as a call for help.

Some of the boys, as they told a passerby, thought the words were unreal, perhaps spirits tormenting a woman.

Moments later, reality caught up with them.

They rushed toward the house. Inside, they found violence in its rawest form. Fatima lay in a pool of blood, struggling for her last breath. An eyewitness said she had been stabbed repeatedly with a sharp object, then struck with her own sewing machine till her injuries became fatal.

The horror did not end with her.

All six of her children were also killed in the most horrific way imaginable. “The youngest child, who was barely a year old, was also thrown into the well. The whole family was erased,” Mallam Bala, a neighbour, told HumAngle.

Following the killings, the Kano State Government formally assumed responsibility for prosecuting the suspects implicated in the murder of Fatima and her children.

A repetition of a tragedy

Just two months earlier, another homicide had shaken Kano. It was at the Tudun Yola Quarters. This one, too, attracted significant attention.

Two housewives, Hauwa’u Yakubu and Zahra’u Aliyu, were attacked in their home. One was stabbed to death. The other, attempting to flee, was set on fire and burned beyond recognition.

The attack occurred in broad daylight, around noon, according to police reports.

Their husband, Ashiru Shu’aibu, said he received an urgent call about a fire at his house. He immediately called his eldest son, Anas Shu’aibu, instructing him to rush there.

What Anas found was far worse than he could have imagined.

“The junior wife was already burning,” he told journalists. “My mother had locked herself in the bathroom. When we forced the door open, we found her dead. Her room had also been set on fire, and the flames were pushed in through the bathroom ventilation.”

At the time of the incident, Ashiru had no suspicions about anyone. He initially thought that burglars might have broken into the house, found nothing, and killed his wives in frustration. Despite the presence of a CCTV camera, the actual perpetrators of the crime were not identified. Police said investigations were ongoing.

What Ashiru’s family did not know at the time was that Umar, the man later accused of killing Fatima and her six children, was connected to the murder of the women as well. It was only two months later, after his arrest in the Dorayi-Chiranchi incident, that Umar reportedly admitted his involvement in the Tudun Yola killings.

Why did he commit such a crime? Some reports indicate that similar incidents have occurred multiple times within Umar’s family. Some link the violence to inheritance disputes, while others speculate that he might have been involved in cultism. HumAngle, however, could not independently confirm Umar’s motive. His father, Mallam Auwalu, recently told journalists that he suspects him of having a hand in the recent murder of his daughter and another woman in the family, all within the last year.

Whatever the reason, two questions remain: given that both of these cases occurred in the middle of the day, how could they have happened without anyone noticing? What does it say about community vigilance in Kano State?

Loopholes in community vigilance

For decades, communities in Kano, like much of northern Nigeria, survived on an intricate web of neighbourly oversight. Everyone watched. When something felt out of place, alarms were raised. Vigilance was the currency of safety.

Today, those walls are cracked.

Since the brutal killings in the metropolis, residents across Kano have begun asking uncomfortable questions about what has changed. Once, neighbours would have raised immediate alarms or observed unusual things. Now, silence often comes first.

“Most of what is happening is the failure of neighbours and the community,” said Aminu Danjuma, a resident of Jakara in Kano Municipal. “How can seven people be killed in broad daylight in a densely populated area and nobody notices?”

Others, especially in the Dorayi-Chiranchi, disagree, insisting that help did come, but too late.

Mallam Bala, a resident, said neighbours eventually intervened and that the suspects were arrested within the area. Still, the troubling question remains. How did the screams go unanswered long enough for seven people to be killed? How were two women burned alive in Tudun Yola without anyone noticing in time?

The contrast between the two neighbourhoods deepens the concern. Dorayi-Chiranchi is densely populated, with houses packed tightly together, while Tudun Yola has wide streets, gated homes, and private guards. Yet both witnessed horrific violence.

“This shows there is a serious problem with vigilance,” Aminu said. “Not just among neighbours, but even among those paid to watch.”

However, in Dorayi-Chiranchi, local vigilantes said they did not suspect danger when Umar entered the compound. He was a relative and a familiar face. Fatima herself opened the gate for him.

“There was no reason to suspect anything,” a man identified simply as Mallam Rabiu said, “He was not a stranger. When someone is known and trusted, you don’t expect such violence.”

That assumption of safety, however, reflects a broader and troubling pattern. Globally, crimes such as femicide and familicide are often committed by people trusted by the victims, such as intimate partners or close relatives, making them harder to detect or prevent through conventional security measures.

Searching for solutions

The aftermath has left many neighbourhoods unsettled. Across Kano, communities are reconsidering how they protect themselves.

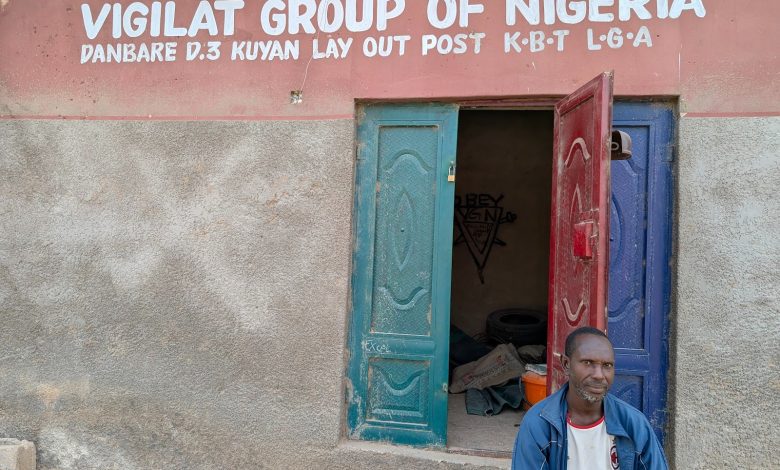

In Kuyan Layout, a developing residential area off the Kano–Madobi road, residents have strengthened security measures, working closely with local vigilantes and officers of the Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps. Since the killings, new rules require that anyone entering the neighbourhood, even if known, be properly monitored.

“We have started documenting every landlord and tenant,” said Mallam Mujtaba Kuyan, chairman of the Kuyan community security committee. “Whenever we see a stranger, we observe them closely so that we prevent danger before it happens.”

According to Mujtaba, the effort goes beyond guards. Women and children in the neighbourhood have received basic training in responding to emergencies. “Our wives and children now know how to call for help if they sense danger, even when no one else is around,” he said.

Still, challenges remain. Many communities struggle to sustain vigilante groups because residents are unwilling or unable to pay consistent stipends.

“Some people contribute, but others don’t,” said Umar Muhammad, the Deputy Commander of Kuyan Layout Vigilantes. “When guards are neglected, they leave for other work. They also have families to feed.”

In Dorayi, authorities have responded by establishing a new police station and installing streetlights. But Muhammad warns that infrastructure alone is not enough.

“Community vigilance thrives on trust and collective action,” he said. “When that trust breaks down through fear of retaliation, lack of institutional support, or the belief that reporting is useless, neighbours become spectators rather than protectors.”

Muhammad added that the rise of thuggery and drug abuse is closely linked to social isolation and economic hardship. “When you have unemployment and no meaningful youth engagement, criminal groups become substitutes for belonging,” he said.

For many in Kano, the violence has forced a reckoning. The question now is not only how the killings happened, but whether the city can rebuild the shared vigilance that once made such tragedies unthinkable.

In a tragic incident in Kano, Nigeria, Bashir Haruna returned home to find his wife, Fatima, and their six children brutally murdered by Umar Auwal, a relative.

This horrifying event exposed the alarming failure of community vigilance, as similar cases of daylight murders went unnoticed. The community's trust-based oversight has deteriorated, raising concerns about safety and communication. In response, local efforts to strengthen security measures and improve emergency responsiveness among residents are underway.

However, challenges persist due to inconsistent support for vigilante groups, highlighting the need for trust and collective action for effective community security.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter