Radio Silence: The Fragility of Independent Broadcasting in Nigeria

Local radio journalists in Nigeria complain they are starved of pay and hounded by harassment and political capture, and are witnessing the collapse of free-to-speak-about-anything community journalism.

In many towns and cities across northern Nigeria, the voices once carried on the airwaves to inform, empower, and provoke reflection have dimmed to whispers of praise songs, sponsored jingles, and obsequious commentary.

Behind the studio microphones and soundproof booths, journalists, mostly young men and women, say they work under suffocating conditions that leave them voiceless both figuratively and literally.

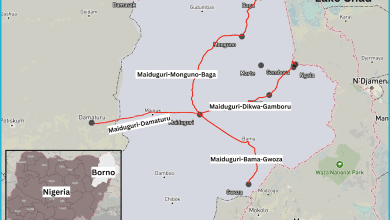

While the region faces intensifying insecurity, mass displacement, and a crisis of governance, local radio and television have largely retreated from their watchdog roles. In their place is a culture of cautious Public Relations (PR) journalism, tailored to please state authorities and avoid retaliation from both government regulators and armed non-state actors.

A culture built on the airwaves

For a long time, radio has been the primary means of communication in northern Nigeria, especially for Hausa speakers. In rural communities where literacy rates remain low and access to newspapers or television is limited, radio serves as a crucial lifeline. It is not merely a medium for entertainment but a trusted channel for education, public health campaigns, civic participation, and political discourse. It is so instrumental that former Boko Haram members have told HumAngle that they laid down their arms and returned to state-controlled areas because they heard constant appeals to do so on the radio.

From the era of Radio Kaduna’s dominance to the rise of community and FM stations in the 2000s, northern Nigeria has nurtured a unique culture of listenership. Markets pause during radio dramas; political discussions unfold around communal radios in village squares. Yet, this cultural power is precisely what makes radio such a potent target for manipulation.

Barely paid, but always owing

Few local journalists report earning a stable income. Most complain they are unpaid volunteers or receive stipends far below minimum wage.

“Many of us are not paid respectable salaries, and irregular, low wages or sometimes no payment at all are common challenges. Some colleagues take on additional freelance work to survive. These financial strains affect our focus, morale, and overall performance as newsroom staff,” said a radio presenter in Gombe, northeastern Nigeria.

“I’ve been reporting for three years, and my salary is ₦10,000, barely enough to feed myself,” said Rukaiya, a young reporter at a privately owned FM station in the north-central region. “Sometimes, I survive on commissions from adverts that I get. Otherwise, we survive however we can.”

The term “however” often refers to morally or socially risky paths. One other young female journalist who spoke with HumAngle on condition of anonymity described engaging in transactional relationships to supplement her income. Others depend on charitable contributions from friends, side hustles like event hosting, voice-over work, or farming, or even resort to panhandling. Some are offered contracts with state governments in exchange for loyalty on-air.

With no employment contracts, health insurance, or protection against harassment, young broadcasters in many communities across Nigeria are vulnerable to exploitation by station owners, politicians, and advertisers.

A 2023 study on media poverty highlights the challenges that affect the growth of rural news journalism in Nigeria. From journalists not well paid to several media houses owing salaries for months or years. “This discourages journalists in Nigeria from going to live in rural areas to practice rural journalism.”

“My salary is barely enough to cover my transport fares to the office, but I have grown so popular in my community that gifts keep pouring in regularly,” said a broadcaster in Nassarawa State, who said she will not demand better pay because she has created an agency that caters to her needs.

When confronted with the suggestion that her views might lead to conflicts of interest and set a negative precedent for young journalists who may succeed her in the future, she said, “We don’t report anything serious; we cover events, read out press releases handed to us, and air drama, music, and shows.”

For some of these journalists, critical journalism is something they admire, but it is not for them to contemplate practising: “We were never trained for this, and we were never told these types of stories are for platforms such as ours,” another radio presenter said.

A reporter in Kano who spoke to HumAngle admitted that not all programmes reflect the real problems people face, particularly because private broadcasters are heavily driven by revenue. “We don’t always talk about these issues because we’re afraid or because the station owners don’t want us airing anything that goes against their views or interests,” the reporter noted.

Regulated into silence

Senior media professionals widely view the National Broadcasting Commission (NBC), which oversees Nigeria’s broadcast sector, as a tool of censorship. Stations that broadcast critical commentary, especially regarding security failures or corruption, risk suspension, fines, or outright closure.

“Therefore, we train our mentees and reporters in a practice that better serves our reality.” The term “reality,” according to this station manager in Nassarawa State, means young journalists are handed rules of engagement; there are words and phrases that are never to be aired, and some stories, even if you witness them, you tell them to your friends and family “off-air.”

The NBC’s lack of institutional independence, with its leadership appointed by the executive arm of government, has entrenched political interference, turning the commission into an enforcer of ruling party interests rather than a neutral regulator.

After airing a report critical of the national security leadership in 2022, Vision FM Abuja faced fines and a temporary shutdown. The message was clear.

“Since then, we don’t touch anything security-related that is sensitive,” said a senior manager at the station. “It’s not worth NBC’s hammer.”

Journalists say the ambiguity of NBC guidelines encourages preemptive censorship. Rather than risk sanctions, station managers vet programming scripts for anything potentially “inciting” or “divisive,” terms that critics say are weaponised against dissent.

Through these, NBC undermines citizens’ access to diverse perspectives and weakens the role of the media as a civic watchdog. The deliberate stifling of the airwaves, in a region already grappling with insecurity and governance failures, intensifies public disempowerment and undermines the remaining pillars of accountability.

HumAngle looked at all TV and radio stations in northern Nigeria and found that up to 15–20 per cent of media ownership lies with the federal and state governments.

Infographics by Damilola Lawal/HumAngle. Infographics by Damilola Lawal/HumAngle.Political capture of the airwaves

Across northern states, local broadcasting is not merely cautious — it is captured. In states like Borno, Sokoto, and Zamfara, station managers say governors and political appointees directly influence their programming. They often determine who gets airtime, what topics are discussed, and which voices are silenced.

“During the last election, I was warned not to host opposition candidates,” said a producer at a state-owned station in Kano. “We were told it would ‘destabilise the peace,’ so we played safe.”

Often, stations are directly owned or heavily funded by state governments. Editorial independence becomes a fiction. Presenters who align with the party line receive rewards such as political appointments, contracts, or PR gigs. Those who deviate risk professional exile.

“It has been a norm in our journalistic practice [for funders] to dictate the tune when you pay for the piper,” said a staff member at a state-owned broadcaster in northwestern Nigeria, adding that not all reports or leads on insecurity can be aired, especially without censorship. “Stories that may cause chaos are rather dropped or rejigged,” the reporter added.

Authoritarianism at the state level

The erosion of press freedom in northern Nigeria is not just an outcome of national-level repression; it is deeply rooted in the authoritarian instincts of state governors who wield enormous influence without sufficient checks.

These governors routinely deploy state security services to intimidate journalists, withhold advertising revenue from critical outlets, or threaten the revocation of broadcast licenses.

Governors in the region have always wielded significant power over local media organisations in their states. In 2016, a TV anchor in Sokoto was forced off air after criticising the state’s healthcare policies.

A broadcast reporter in Borno faced detention in 2021 for “cyberstalking” after exposing purported corruption in post-insurgency reconstruction contracts.

Such actions rarely provoke public outrage, partly due to a climate of fear and partly because the press itself is too compromised to amplify its oppression.

Caught between armed groups and the microphone

In parts of the North West and the North East, fear of armed groups has further stifled local media. Journalists in the northwest, northeast, and north-central states describe receiving direct threats after airing reports perceived as critical of armed groups.

“We stopped reporting kidnappings in some areas,” one radio editor in the north central told HumAngle. “They called and said if we mentioned their names again, they would burn down the station.”

“The threat of violence, whether from state actors or armed groups, has influenced editorial decisions,” a radio presenter in Maiduguri told HumAngle. “Sometimes, we have to downplay or completely avoid certain sensitive topics for personal safety and the safety of our families and colleagues, as well as to secure our jobs. It’s a constant internal conflict between professional duty and survival.”

These threats come amid a broader climate of insecurity, where state protection for journalists is practically nonexistent. As a result, communities find themselves under siege, yet they lack a voice or a platform to express their concerns.

From watchdogs to whispers

In a healthy democracy, local media act as civic mirrors and watchdogs—holding power accountable and giving voice to the voiceless. But in much of northern Nigeria, local radio has been reduced to echoes of power, playing jingles and feel-good stories while real crises unfold off-air.

The tragedy is not just professional; it is societal. When local media fail, communities lose more than news; they lose agency.

Suleiman Shuaibu, a business development specialist in Abuja, highlights that international broadcast stations, airing in local languages like Hausa, are uniquely positioned to pose and tackle challenging questions. “The sole constraint they face is their inability to address context-specific topics that pertain to individual communities.” They focus solely on major news developments.

The VOA Hausa has ceased operations in light of Donald Trump’s decision to freeze US foreign aid and activities. The presence of BBC Hausa, Dutch Welle, Radio RFI, and others is notable, yet their future hangs in uncertainty due to various European governments implementing policies aimed at reducing expenditures on extensive and ambitious initiatives that do not directly benefit their citizens.

Towards a new frequency

To reverse this trend, several experts who spoke to HumAngle on this subject call for a multipronged approach: “fair remuneration and protections for media workers, the depoliticisation of regulatory bodies like the NBC, and coordinated efforts to protect journalists from both state and non-state threats.”

Support can also come from within: local media houses banding together to resist political capture, civil society amplifying their role as watchdogs, and donors investing in long-term media independence projects.

The stakes are high. In a region where radio remains the most accessible and trusted medium for news, revitalising local broadcasts is critical to preserving democracy.

This report was produced by HumAngle in partnership with the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) as part of a project documenting press freedom issues in Nigeria.

In northern Nigeria, local media has shifted from being a civic watchdog to a voice of caution due to governmental and armed group pressures. Journalists face poor pay and have been deterred from covering sensitive issues because of threats and regulatory censorship.

The National Broadcasting Commission exerts political control, and state governors influence media through political appointees and intimidation.

Broadcasters avoid controversial topics to avoid repercussions, weakening the role of the media as a free platform for diverse perspectives and accountability.

Local radio is the primary source of news in the region, vital for education and discourse. However, the pressures faced by journalists result in a shift towards PR journalism benefiting state authorities.

This situation leaves gaps that international broadcasters, like BBC Hausa, struggle to fill due to their focus on major news, not local concerns.

To preserve media independence, experts suggest fair pay, depoliticization of regulators, and collective resistance within media houses. Enhancing radio's role is crucial for sustaining democracy in northern Nigeria.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter