Poor Treatment Of Young Africans Living With HIV Threatens Global Eradication Plans

Young people living with HIV in West and Central Africa say they still face abuse, discrimination, and disappointing healthcare services. This reality, in turn, makes ending the epidemic as a public health threat in the next decade a lot more difficult.

E.L. found out she was HIV positive eight years ago. When her husband cautioned her against telling others, she thought he was exaggerating. Then, one day, while chatting with her mother-in-law, she seized the opportunity to ask if the older woman could associate with someone living with the virus.

“Her response was appalling,” remembers E.L., who asked to be identified by her initials for safety reasons. “She said even if her child were positive, she wouldn’t eat with them again.”

The 28-year-old is resident in the Ashanti region of Ghana, where those living with HIV continue to face stiff stigma. People who have contacted the virus are forced to keep their status secret out of fear that they will be ostracised or harmed, she says.

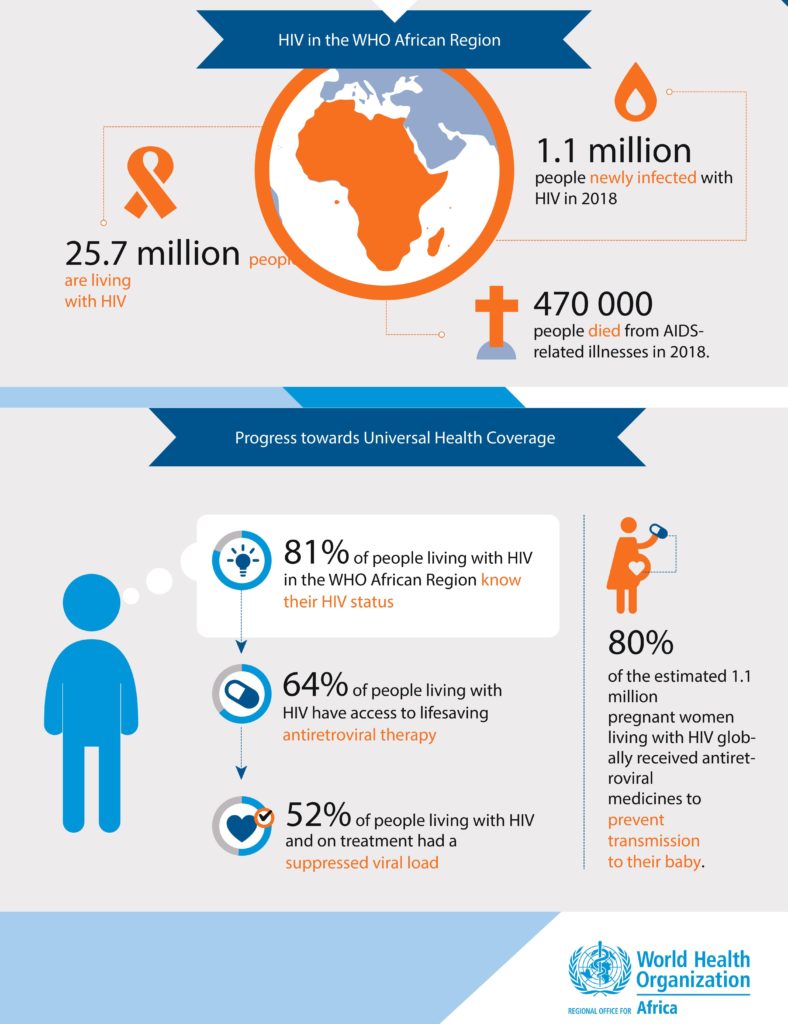

HIV originated in Cameroon, West Africa, in the early 20th century and became a pandemic in the 1980s. Since then, though much progress has been made to push back the spread and the infection’s deadliness, it has refused to go away. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), HIV has killed over 35 million people so far, 700,000 of those in 2020.

Sub-Saharan Africa has remained the most-affected region, recording not only the highest prevalence and deaths but also the greatest number of new infections. Over two-thirds of people living with HIV across the world are in Africa and nearly two-thirds of new infections are from the continent.

Among the targets set by the United Nations through the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), on the other hand, plans that 95 per cent of people living with HIV know their status, of which 95 per cent are on treatment, and of which another 95 per cent are virally suppressed — all by 2025.

Similarly, ambitious targets set for 2020 had not been met. So this year, the theme of this year’s World AIDS Day, celebrated every Dec. 1, is ‘End inequalities; End AIDS,’ to draw attention to people who have been left behind in the HIV response and make access to services more equitable.

Unending discrimination, threat to life

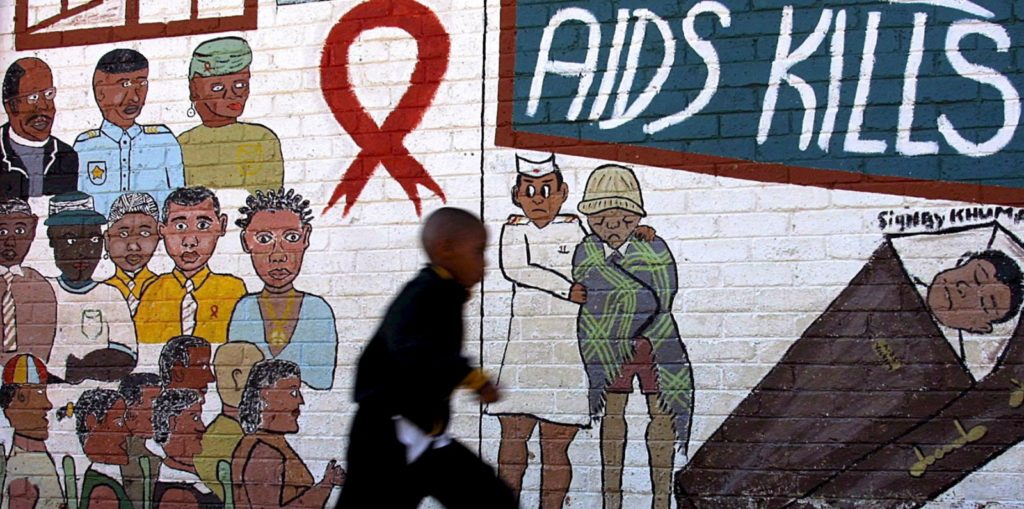

Achieving global targets within the next decade will not be a smooth sail, especially as misconceptions about HIV are still widespread across Africa, making access to healthcare difficult for those affected. The infection is assumed to be a death sentence and people are often hostile to those who have it.

When Ismaël Nkono, 23, who lives in Yaoundé, Cameroon, got diagnosed with HIV in 2017, he found strength in his mother and family. He, however, notices that many people in the larger society are still ‘very ignorant’.

“Information about HIV is not accessible to everyone. Many still believe that living with it is something like a malediction, that it is witchcraft,” he says. “I want to be seen as a normal person. I want to share moments with people without them looking at me as if I was [different]. That is the real problem.”

In Ghana, E.L. works with a non-profit, Young Health Advocates Ghana (YHAG), to prevent the spread of HIV among young people as well as provide educational and psychosocial support. As a paralegal, she attends to cases of human rights violations and refers relevant ones to lawyers. Playing these roles, she continues to see many people have their rights trampled on.

In one of the cases, an HIV positive woman was severely beaten by a man who saw her with his son and claimed she wanted to infect the boy. At the health facility, they asked for a police report so that the assaulter could be arrested. But the woman, knowing she would have to divulge her status at the police station and it might leak to others, decided to let the matter go.

“When she came out from the hospital, the man threatened that if he saw her with any man in the community, he would kill her. It was then that the woman decided to approach us. The man was so proud to tell us that before somebody infects others with the virus, it is better to kill that person.”

Even health workers are not exempted. According to E.L., HIV is treated like a contagious disease in many facilities and health workers would often wear multiple hand gloves, three or more, when a patient discloses their status.

There have also been instances when doctors do not respect their patients’ privacy. One person complained to E.L. last year during the annual stigma index study that her doctor had called her husband to inform him she was HIV positive. By the time she got home, the news had spread.

“She was assaulted. The time she came to us, she wanted psychosocial support. We were in the process of giving her everything when she passed on because of the trauma. We lost her last year,” E.L. says. “She couldn’t take it that everybody was against her and the whole community saw her like she was a devil.”

Abdulrazaq (last name withdrawn), an entrepreneur based in Abuja, Nigeria, has been a victim of mistreatment from those who should know better too. He was a first-year pharmacy undergraduate when, urged by his peer educator-friend, he took an HIV test and discovered he was positive. But because of how workers at the facility openly gossiped about their clients, he left and stopped answering their calls. He soon fell sick after returning to school. He started losing weight and had constant headache. He eventually treated both HIV and Tuberculosis. He could not walk, was bedridden for six months, and had to drop out of school.

He has not returned to school since then and has instead focused on raising money to sponsor his siblings’ education. He now gets his antiretroviral drugs regularly from a facility nearly 200km away in Kaduna State (North West). He agrees it would be simpler if he transferred to a different facility in Abuja, but two concerns prevent him from doing so.

One, the service in Abuja could be worse. Already, in Kaduna State, when his collection date is due, he has to wake up at 6 a.m. WAT, get to the facility half an hour later before the nurses and cleaners, drop his card, and get assigned a number. He then waits to get called. The process takes several hours.

The second reason is he fears he is more likely to run into familiar faces in Abuja. He had fled from the facility where he first got tested for the same reason.

“I don’t see why you’re working in a place like that and there’s no confidentiality. Just imagine somebody meets me and says, ‘I heard you’re HIV positive.’ ‘Where did you hear it from?’ He now says they’re discussing you now. Do you think I’d go back to that place again? I’d even prefer to even die than return there because if they can be giving me drugs and still talk about my health, then I am not safe,” he says.

“And they are still doing it. In fact, I have friends who are positive and don’t go back to their health facilities because of this.”

For key populations such as men who have sex with men, transgender people, prison inmates, sex workers, and drug users, the discrimination often comes in multiple layers. Eleven out of the 24 countries in West and Central Africa have laws prohibiting same-sex relations, including Cameroon, Chad, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Mauritania, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Togo.

“I feel even if the government revokes or revisits the law, it will be difficult to change the average mindset,” says Kelsey Brookes, 24, a queer person based in Lagos, Nigeria. “I still feel discriminated against even though I can’t see the discrimination so to say. I just think: God, they hate you; you’re gay and you’re HIV positive.”

Gab-cliton, 28, who runs an NGO that promotes the welfare of sexual and gender minorities living with HIV in Lagos says it is difficult for people in the community to find safe spaces. “It has been a rollercoaster having to change facilities and looking for a place that will be more comfortable, where I don’t feel stigmatised because I’m queer or HIV positive,” he stresses.

Meanwhile, paying attention to minority groups is critical to ending the epidemic. According to WHO, key populations and their sexual partners accounted for over half of all new infections in Africa in 2018, especially in West and Central Africa where the figure was as high as 64 per cent.

Stopping school, attempting suicide

Schooling can be a challenge for young people living with HIV because of the lack of personal space. They are unable to take their medication regularly without risking having others find out. And when one person finds out, it is only a matter of time before the information spreads, leading to stigma and then thoughts of dropping out.

Part of E.L.’s work involves counselling young people living with HIV and making sure their health does not affect their careers.

“We have a lot of people who actually dropped out of school because of that, especially those who have lost their parents to the virus and are under the care of others,” she says.

“If I’m to estimate, this year we have about 12 people that I know of who nearly dropped out until we intervened; mostly secondary school students. But, for university, those who have dropped out or have not been able to proceed. They are countless; I can’t even predict.”

Although E.L.’s team has been able to persuade some young people to return to school, two cases have been documented this year of people committing suicide after dropping out. Sometimes, they learn of at least two deaths in three months. And other times, there are zero incidents.

“But it is not all the time cases like this happen that we get to hear of it. If somebody doesn’t report, you might not know,” she clarifies.

“What usually happens is that they would stop taking their medications and eating well because of the pressure from the community. Then the person would fall sick. It wouldn’t take long before they become bed-ridden and eventually, if we don’t take care, we lose them.”

Difficulty getting, retaining jobs

There are many ways living with HIV affects a person’s job security. They could be afraid of applying because they are not sure they would be allowed to go periodically to get their medicines. They could switch career paths. The work environment could be made unconducive due to stigmatisation or excessive expression of sympathies. Or they could be sacked or denied employment.

“Sometimes, you want to apply for a job and they say you have to do an HIV test. They say it doesn’t matter what the result is but it’s a lie! I’ve had friends that apply, especially for hotel jobs, and when they find out, they will not even call you again,” says Abdulrazaq.

One of Abdulrazaq’s friends used to work as a chef at a hotel. He was laid off when they found out he was HIV positive under the pretext that he could infect guests through the meals. He kept to himself after he lost the job and found solace in hard drugs. He also stopped taking his antiretroviral drugs.

He died in April 2020. “In his room, alone,” Abdulrazaq says. When his body was discovered days later, it had already started to bloat.

“That would have happened to me too because I started taking drugs at a point, but I stopped. The only thing I do now is smoke weed, because when I think about all the stress and the hard life that I’ve gone through just because of my health problems… A lot of people are actually depressed but you will not know.”

Gab-cliton likewise believes the epidemic cannot be eradicated unless barriers to employment are addressed. He points out that young people who are not able to secure jobs may resort to sex work or vengefully infect others. It is also difficult for persons living with HIV who do not have access to square meals to stick to their treatment regimen. This will, in turn, lead to increased viral loads.

“Most of them still assume they are undetectable, so they engage in unprotected sex with their partners or others… and they keep spreading the virus to other people.”

Meeting the challenge of ending HIV

While the number of new infections has dropped gradually since 1999, it is not reducing fast enough for global targets to be achieved. And the factors driving these infections include the stigma and ignorance surrounding the illness, economic inequality, as well as the treatment of gender and sexual minorities.

E.L. estimates that, out of 10 Ghanaians, at least nine believe till today that someone infected with HIV is doomed to die within five to 10 years.

“The information they had about the virus when it came in the 80s is the same information they have right now,” she observes. “They don’t know anything about antiretrovirals. Sometimes they stigmatise you but they don’t even know that they are stigmatising you; they feel they are running away from trouble.”

Ignorance about the virus has naturally affected those infected as well. Many who are diagnosed believe they are about to die and it takes a lot of effort to convince them otherwise. Lives have been lost too because of overdependence on clerics and herbalists.

Young Africans living with HIV are thankful that the antiretroviral treatment, which is ordinarily unaffordable for most, has been made accessible through government and non-governmental interventions. But they say there’s more work to be done if they are to be guaranteed the best quality of life possible.

“The only thing that has gotten better is access to drugs,” says Abdulrazaq. “Asides that, I don’t think any other thing has changed… we’re just going round and round, we’ll come back to the same spot and then go forward a bit, then still come back to that same spot.”

For the queer community, Kelsey believes that if they were not discriminated against as much, their members would be more willing to get tested and treated for HIV. Otherwise, he adds, “curbing this epidemic will be a very far cry.”

He explains: “I work from home because I am afraid that, one of these days, I might be one of these unlucky people that are caught on the road and beaten and then the government does nothing because you are gay, you walk like a girl, you are homosexual, so whatever beating you get, you merit it. If I am that scared of going outside, would I want to go to a hospital? Even though I test positive, will I want to get treated?”

More importantly, young people want to become active participants in the HIV response so that they can contribute to solving the problems facing them.

“Globally, especially in Africa, HIV continues to disproportionately affect young people in all forms, yet we are marginalised and relegated to the role of dependents receiving services rather than autonomous actors,” says Ekanem Itoro Effiong, Chair of The PACT, a global coalition of youth-led organisations working on HIV and sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR).

“We have repeatedly demonstrated our ability to innovate and lead HIV responses in our communities. The interventions we are leading and have led must be recognised as critical components of national, regional, and global HIV responses,” he urges.

Itoro Ekanem adds that immediate attention should be paid to adolescents living with HIV, both in and out of school, and children, especially as many of them who need medication are currently not getting it. “We urge governments to launch national campaigns as soon as possible to ensure that children are tested for HIV, treated, and holistically supported as they grow and develop,” he concludes.

E.L. is convinced that as much as the government urges people to prevent getting infected, it should also create awareness about acceptance of people living with HIV, adherence to treatment, and the risks of reinfection. The authorities, she says, should devote resources to protecting people getting victimised because of their status and enforcing relevant laws.

Recently she was with a group of friends and one of them said she could never eat with a person if she knew them to be HIV positive. Hearing this, tears started rolling down her cheeks uncontrollably to the shock of her friends.

“They just hate those who are positive,” she says. “And when will they accept us and make us feel like we are humans? We have been hiding for a long time and I don’t know for how long we will continue to hide. I don’t know when we can come out and tell people that we are also humans with emotions. I don’t know.”

This article was published with support from The PACT.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter