Poor Pay, Zero Growth: Nigeria’s Casual Workers Sinking into Despair

From primary school nannies to cleaners in tertiary institutions, Nigerian casual workers face exploitation, lack of access to benefits, job insecurity, poor pay, and inadequate statutory protection.

Bilkisu Haruna’s* voice carried over 25 years of frustration, rising through the phone. Her life, which she expected to change when she got a job at Ahmadu Bello University (ABU), Zaria, Kaduna State, in northwestern Nigeria, in the early 2000s, after years of menial labour, was swallowed into an endless pit of suffering and bitterness.

Being a casual worker in Nigeria is to drown in a cycle of hopelessness, a feeling she knows too well.

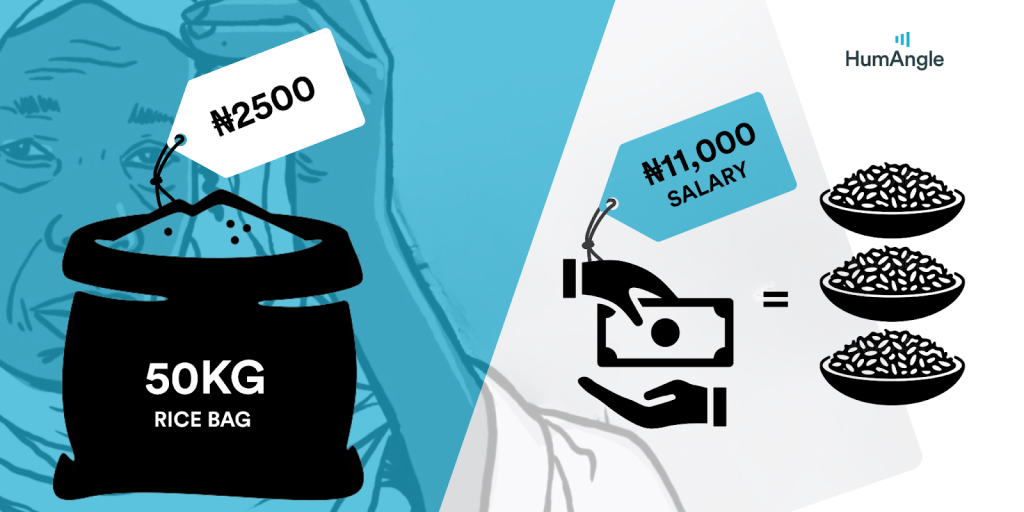

“When I got hired, I was paid ₦3000, which was ₦100 per day. It was a fair offer because that money did more for me than what I earn now,” Bilkisu told HumAngle.

At that time, a 50kg bag of rice cost about ₦2500, but the cost-of-living crisis has increased it to an amount that she and many other Nigerians can no longer afford. Her current salary of ₦11,000 can buy only an estimated three bowls of rice, without enough condiments or other necessities to feed her family.

However, most of her salary goes towards paying transport fares to work. She pays an average of ₦500 for a tricycle ride or ₦300 for a motorcycle ride to get to work daily.

“I usually take a bike to go to work, then I walk back home, despite how far it is,” Bilkisu explained, adding that the journey takes her around 50 minutes. “And if you go late, they sometimes send you back without payment. I rarely miss work for any reason, but I am still in the same place after almost 25 years.”

Workforce casualisation in Nigeria

A study by the International Journal of Business and Social Science describes casualisation as a form of temporary employment that has become a permanent job, yet lacks statutory benefits, such as adequate pay, medical insurance, and a pension. The system also prevents casual workers from the right to unionise. According to a 2018 Nigerian Labour Congress report, an estimated 45 per cent of Nigerians are casual workers, with a high prevalence at both the federal and state levels across all sectors.

Recently, the Minister of Labour and Employment, Muhammad Dingyadi, warned against the growing normalisation of casual and precarious work arrangements in Nigeria’s labour market, describing the trend as a threat to workers’ welfare and national productivity. Dingyadi noted that many organisations now rely on casual and contract staffing to cut costs, often at the expense of workers’ security and rights.

Bilkisu is a mother of nine; she lost her husband not long ago. Before his passing, he worked as a security guard and often catered for the family, but that entire responsibility now lies on her shoulders. It is even difficult now, as she is observing ‘iddah’, an Islamic practice that mandates widows to mourn their spouses for four months and ten days, and that restricts their movement and activities.

“Some of my coworkers helped me work for free when I was taking care of my husband while he was sick, but the work is tiring, so I just made an arrangement with someone I could pay for the duration of my mourning period,” she said.

There is no provision for casual workers, such as Bilkisu, to receive paid leave during such situations. The few instances she has received grace were when she was very sick. Sometimes, they would ask her to get checked in the hospital, but they don’t give her drugs. Health insurance is not something she can afford on her own.

“Sometime back, they used to let us see a doctor for free, including admissions. But, I think for the past 10 years, we have to pay ₦1,000 to see a doctor, and no drugs are given; they will only write you the prescription,” she recalled.

For Bilkisu, she harbours no big dreams; she just wants a better salary so that she can take care of her children and grandchildren. The university has no provision for casual workers to enrol their children in the staff school, leaving them without benefits for all the years they have worked there.

Over the years, the cost of hostel accommodation has changed, but the salaries of casual workers have remained the same. A former student, who asked not to be named, told HumAngle that she paid around ₦7,000 when she first got into the university in 2018. However, she paid ₦14,000 before graduating, which is still the current price for a hostel bed space at the university.

Bilkisu supplements her income by fetching water, washing dishes, doing the laundry, and running errands for students. However, the pay is low. Sometimes students can pay ₦50 or ₦100 to wash plates, unless it is a monthly arrangement, in which case it can be up to ₦1500. The side jobs are also highly competitive, as everyone is scrambling to get what they can.

“Sometimes, you also have to find something to buy and eat at school to get through the day. If not for that extra work, I would not even go to work because I am constantly in debt,” she complained.

These menial jobs have sustained Bilya Nafiu* for over 30 years. At over 50, Bilya finds himself running errands for students young enough to be his children. He shares Bilkisu’s experience, living from hand to mouth as a casual worker.

“When I started, I was being paid ₦1500. I currently earn ₦13,500. Even when other job opportunities come up in the university, such as security jobs, they hardly give them to us, even if we are qualified, ” he lamented. This makes it impossible to become a permanent worker. Sometimes, they make it to the interview stage, but nothing comes of it.

What does the law say?

Hikmat’llah Oni, a Nigerian lawyer, noted that there is no explicit definition of “casual worker” in the Nigerian Labour Act. She, however, cited Section 73 of the Employees’ Compensation Act 2010. The Act defines what it means to be an employee: a person employed by an employer under an oral or written contract of employment whether on a continuous, part-time, temporary, apprenticeship, or casual basis and includes a domestic servant who is not a member of the family of the employer including any person employed in the Federal, State and Local Governments, and any of the government agencies and in the formal and informal sectors of the economy.

The legal practitioner stressed that under the Minimum Wage Act, three categories of people are exempted: part-time workers, seasonal workers, and piece-rate workers.

“What most establishments do is lump casual workers with these three categories of workers in an attempt not to pay the minimum wage, which is unfair because they sometimes do the hardest work; their bargaining power is also not the same as that of one in full-time employment,” she explained.

The casual workers in the university said they’ve spent decades in the job, but they struggle to pay their bills.

“We have tried to seek help; some of the previous students we know have become professors, but they don’t listen to us. We also tried to seek help from the Student Representative Council (SRC), especially regarding the late payment of salaries, but they don’t even listen to us anymore,” Bilya said.

In the past, the university provided loans to casual workers, but it eventually stopped. They fear the workers may refuse to repay the loan, leaving them without an outlet for other financial assistance in emergencies. The repayment system was also a problem they encountered, as almost half their salaries were taken off every month to pay back the debt. Another issue was the lack of privacy, where news would spread around the school about who was benefiting from that system, making them feel exposed.

With a daily transport fee of ₦300 to ₦500, it is almost impossible for Bilya to even handle his family affairs. When he is sick, he has to find an outsider to do his task, as all his older children are women, and he doesn’t feel safe enough to send them to do his work at the male hostels.

The horrible hostel conditions make it harder for them to do their jobs. Immediately after they clean, toilets can get dirty again, and that can get them in trouble with their supervisors. Even when they manage to save water for the next day, students can sometimes sneak in and use it all up before the next morning, Bilya explained.

Washing the bathrooms also requires them to carry buckets of water up the stairs, and sometimes they have to buy brooms to clean them, because the school rarely provides them with the right tools anymore, taking much more from the little they earn.

“With all I have poured into the school over the years, even the role of a director is not adequate to compensate me,” he claimed.

He works part-time as an electrician because the school has its own official workers. He gets side gigs from students to handle minor tasks, such as fixing faulty sockets and light bulbs, which can pay ₦100 or ₦200 per task. Despite these obstacles, he has managed to educate his children.

As coworkers save from the little they earn for rainy days by contributing ₦1,000 monthly, he sometimes benefits from the kindness of friends and family.

“When we started working, people kept telling us to be patient, that it would pass, and one day we would be leaders of tomorrow. But many years have passed, and nothing has changed. I can go three years without buying a simple shirt for myself because of outstanding debts. We are suffering, but we are also trying to practice contentment,” he explained.

Sometimes, the management deducts from their salaries without explanation, even if they didn’t turn up late or miss work, and almost nothing is done when they complain.

In one particular month, Bilya received only ₦8,000 without an explanation. He tried to follow up, explaining that he had not failed to do his duty that month, but he still didn’t receive the outstanding payment. These days, he doesn’t bother to complain even when his salary falls short of the expected amount. He understands that life as a casual worker also means he can be fired if he steps outside the lines.

This exploitation is common across different sectors in the country. In 2011, for instance, the Nigerian Labour Congress shut down 15 Airtel Communication showrooms across the country to protest the alleged casualisation and dismissal of 3,000 workers. In 2024, HumAngle published an investigation into the maltreatment and exploitation of some casual workers at the Dangote Refinery in Lagos.

“Casual workers, in most cases, do not have a formal contract, which is the prerequisite for becoming an employee under Labour Law. So, in reality, they don’t get the full ‘package’ of employment benefits, leaving room for cutting their salaries without explanation, because they don’t have a work contract protecting them. Keeping casual workers for years without a contract is exploitative,” the legal practitioner explained.

Different strokes

The cleaners at ABU are categorised into student affairs and health services, with those in health receiving higher pay due to hazardous conditions. The casual workers earning ₦13,500 are those who wash bathrooms and clean gutters, but people who just sweep the compound earn ₦11,500. HumAngle’s findings show that the casual workers are not given any payslip or physical evidence of their salaries. Every month, they queue up at the school bank to collect their cash payments.

Hikmat’llah explained that the labour law does not require the provision of payslips. However, it requires employers to maintain records of wages and conditions of employment, which can lead to further exploitation of casual workers.

As a casual worker under health in ABU, Nabila Bello* earns ₦22,000 or ₦22,500, depending on the number of days in a month. Before she got her job 10 years ago, she dabbled in business in her home, which still helps supplement her income. Even with a degree, there is no pension, gratuity, or hope of promotion. Her transport to and from work costs ₦700, which is almost what she earns per day.

Further research shows that casual workers are more likely to experience more disadvantages compared to permanent employees, such as inadequate statutory protection, social security, and union membership, and are least likely to receive compensation for injuries.

“Sometimes, I can spend ₦500 if I leave home early and trek to reduce transport fare,” she recounted. Being in a supervisory role means she doesn’t do the cleaning herself, but missing a day’s work also means losing her pay for that day. Unlike the cleaners, she cannot delegate her task. Nabila hopes to get a bigger opportunity with her degree someday.

This experience is common for other casual workers around the country. In a Federal College of Education in Adamawa, northeastern Nigeria, Maimunah Ado* pays ₦400 daily to get to work from her ₦18,000 monthly salary. Her most significant challenges are the workload, especially on Mondays, which requires extra work, such as cleaning offices. But she has no choice but to keep showing up to work every day.

It is almost impossible to survive without side jobs.

After a long day at work, 45-year-old Ilya Adamu* sets his sewing machine to work to supplement the ₦13,500 he earns as a casual cleaner at ABU. Every day, he spends about ₦1,000 on transport to and from work. With four small children still in school, he is barely scraping by to make things work.

“There are no promotions, and the pay is very little. It makes us feel very stuck and hopeless. Even though payment comes in every month without fail despite the delay,” he said.

HumAngle learnt that the school had months of unpaid wages owed to the cleaners for work completed in 2020. However, the school only paid part of the money after the workers went on a five-day strike in 2024. Some have given up on getting the rest of their money back. Some workers in the ABU Kongo campus claimed that they still have a month’s salary pending from that time, but the sources from the Samaru campus said they have been paid in full.

Bilya, one of the few who ensured the strike’s success, explained that during the strike, they ensured no cleaner violated it and went to work. Some were delegated to go through the school and stop any staff from working. This strike worsened the already horrible living conditions of the students in the school, making the environment unlivable.

Despite multiple attempts to reach out to Ahmadu Bello University for a response to these allegations, all emails, including follow-ups, have remained unanswered.

A health challenge

As an asthmatic patient, 50-year-old Halimah Ashiru’s* work as a nanny in Kaduna State poses a lot of risk and triggers for her condition.

“Even when you say you are sick, you are expected to show up at work, unless the sickness is so severe that you can’t get up. There was a time I had a terrible attack in school, and they had to return me home. After that time, my work got reduced, but I had to go back to work the next day, even though I had a smaller attack that day too,” she told HumAngle.

This is the reason why she doesn’t sweep anymore, unless it is a less dusty place. The Islamic school she works at has two segments: it runs the Western education segment on weekdays and the Islamic school segment on weekends. When she began her job ten years ago, earning ₦3,000, the Islamic segment was from Saturdays to Wednesdays.

“I can’t afford an inhaler, they said I have to keep using it, and I know it’s not sustainable for me. I just asked them to write me other drugs that can help manage my symptoms, and it helps a bit. I also ensure they are always available. Sometimes, I can go months without an attack,” she explained.

Her condition usually worsens during harmattan, and sometimes even during the rainy season. Still, she tries to avoid her triggers as much as she can, while working overtime to sustain her family.

Hikmat’llah explained that the Employee Compensation Act provides for claims for health or work-related injuries, entitling casual workers to compensation and similar benefits. According to the Labour Act, employees are expected to be formally hired after three months. Some organisations exploit this loophole to fire and rehire casual workers every three months, or hire new people, to avoid violating the law. This further contributes to the lack of job security for casual workers. But many workers like Halimah are not aware of these provisions.

Apart from Halimah’s salary, the school sometimes provides food items, especially during Ramadan, and free sacks of rice can arrive at random times. However, her salary has not changed much, even amid the cost-of-living crisis. She currently earns ₦8,000 monthly.

Her main task is cleaning, but she also serves as a nanny for the children of teachers and other older students at the school during classes.

“My workload has reduced. I used to sweep the classes and environment, clean toilets, and take care of the younger students, especially when they needed to use the toilet. I used to be the only nanny, but they hired another one recently.” Before then, she had worked in residential houses as a cleaner.

Once, a massive fight with the proprietress led her to quit for a while, but the woman reached out, apologised, and asked her to resume. “If I go late, she removes a small part of my salary, usually ₦500 or ₦700, so I try to make it on time.”

The cost-of-living crisis has changed so much for her. The good thing is she lives close to the school and doesn’t need to pay for transport.

“My salary can only buy things like soap, detergents, and similar items. I keep working because I can’t afford not working,” she said. Halimah takes on part-time cleaning work in residential homes, and she also holds another side job that brings in an extra ₦10,000 per month. On days she has work in the morning, she shows up at the other job in the evening.

This combined salary is really not enough to take care of her family, but immediately the salary comes in, she tries to stock up on some food items- sometimes the food can last for 10 to 12 days and on other days, she looks for other part-time jobs.

“My family members also try to help in their own ways,” she added.

A positive experience?

Grace Amos* started working as a cleaner at a private hostel at Kaduna State University in 2023. Before then, she ran a small business at home, selling pap and firewood. Her salary is currently ₦40,000, which is still below the current minimum wage of ₦70,000.

“I am satisfied with my job. The biggest challenge for me is dealing with students. We work hard to keep the environment clean, and they will make it untidy by the next morning, which makes our work harder,” she said.

Grace sweeps the hostels, washes the toilets, and cleans the hostel’s surrounding area. Her work starts by 7 a.m. and ends by 2 p.m.

“I also supplement my income by taking small jobs from the students, such as laundry,” she said, noting that this makes it easier for her to help herself and her family.

This experience is shared by thirty-five-year-old Margaret Joseph*, who started working in the same hostel in 2021.

With a secondary school certificate, she doesn’t see much hope for a bigger opportunity. “There is no chance for career growth when you work as casual staff, but we can only hope for more salary increases. I never expected that I could be paid this much as a cleaner,” she said.

Even without other work benefits such as pensions, insurance, or promotion, they feel content because their working conditions are much better than those of many others.

However, investigations show that the working conditions differ from hostel to hostel. The university has regular and private hostels, run by different companies, which vary in cost. Maimunah*, a student at the university, said she paid ₦207,000 for accommodation at a private hostel on campus this year, up from ₦140,000 in 2024.

Inadequate working tools

Zaliha Ahmad* started working at Kaduna Polytechnic in northwestern Nigeria in 2020. Her biggest challenge is the inadequate provision of cleaning supplies, which makes them dig into their pockets to cover the gap.

“Students are always complaining about the conditions of the bathrooms, but we usually have to use our own money to buy detergents and bleach. We can go three months without receiving cleaning supplies,” she explained. She is ideally supposed to clean twenty toilets from her assigned two floors daily, but due to inadequate cleaning supplies, she sometimes cleans an average of three to four a day.

There is also a limited number of cleaners, putting the burden of washing the bathrooms, halls, and even clearing overgrown weeds around the hostel on the casual staff. Sometimes the work gets too overwhelming, and they have to outsource the task to someone else and pay them for their services.

“We don’t complain because that’s how it has always been; we just find our way around it. But it’s better than staying at home without a job. I try to run small businesses on the side to supplement my income,” she told HumAngle.

With a monthly salary of ₦20,000, Zaliha spends an average of ₦600 to get to work every day. Sometimes she walks back home, which takes her almost an hour.

The only other benefit she receives is during Ramadan, when the school provides a form with basic items such as spaghetti, sugar, and other items they may need, and, based on the choices they make, a particular amount is deducted from their salaries every month until they finish paying back. This helps them immensely.

In 2020, the Nigerian Senate considered passing the ‘Prohibition of Casualisation Bill 2020,’ which aims to criminalise casualisation. The bill also recommended a bail of ₦2 million or two years’ imprisonment for violators. Although it has passed the second reading, it has yet to be signed into law, leaving Nigerian casual workers at the mercy of their employers.

*Pseudonyms were used to protect the identities of the sources.

Bilkisu Haruna, a casual worker at Ahmadu Bello University in Nigeria, exemplifies the struggles faced by casual employees who are trapped in a cycle of underpayment and lack of benefits.

Despite working for 25 years, Bilkisu earns ₦11,000 monthly, barely enough to meet basic needs due to rising costs. Most of her salary goes to transport, and she also manages menial side jobs to make ends meet. Her situation is exacerbated by a lack of formal labor rights, as over 45% of Nigerian workers fall into this category, which often denies them minimum wages, health benefits, and the right to unionize.

This situation is mirrored in multiple accounts of casual workers in Nigeria who face inadequate pay and working conditions.

Many casual workers, such as Bilkisu and her colleague Bilya Nafiu, lack job security and are excluded from benefits and promotions. Legally, there is no clear definition of casual work in the Nigerian Labour Act, leading to their exploitation by employers who avoid offering full employee benefits. The pending 'Prohibition of Casualisation Bill 2020' aims to address these injustices by making casualisation a punishable offense, but it has yet to become law, leaving many workers without protection or prospects for improvement.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter