Plateau Farmers Turn to Land Documents to Reclaim Their Fields Amid Violence

Facing continued deadly attacks and land grabs in Plateau State, farmers rely on land documents to avoid dispossession and to secure their fields and homes. The papers bring hope of ownership, but cannot shield them from violence.

Sarah Ishaya doesn’t seem to remember the day the attackers came in 2021, but what she cannot forget is how they almost took the lives of two of her sons. It was around 6 a.m. that they started hearing screams from neighbouring houses, and before she could flee with her family, the attackers were already at her compound, a flat beside the main road in DTV, a rural community in Bassa Local Government Area (LGA), Plateau State, in North Central Nigeria.

“They stabbed one of my sons, and the other one went to help him fight back, and he was also stabbed on his hand,” Sarah told HumAngle, from one of her farms, just about a minute’s walk from the house. Eliya, the one who sustained a stab on his hand, was also on the farm with his mother when HumAngle visited. “It was scary, but I wanted to get my brother to go with us,” he said.

Sarah and her family eventually fled their house that morning to the main market in the community, and later to Jos, the state capital, where they stayed for two weeks. When they returned, their house was burnt down. “That was the fourth time we were re-roofing the house due to an attack,” she said. Her farmlands were not spared. “We lost a lot of money,” she added, struggling and failing to put a figure to it; “It was a lot.”

The forty-five-year-old was born in Bassa, but she moved to nearby Jos North LGA, where she spent her formative years, and returned home when she got married in 1991. Since then, she and her husband have been farming a variety of crops, especially maize, cabbage, pepper, tomatoes, and Irish potatoes. The proceeds, she said, are used for the basic needs of her household of ten.

“I used to run a provision kiosk at the entrance to the house, but due to the continued destruction, I have not made enough money to reopen, so the farms are the main source of income,” she said.

More than 27,000 farms in Bassa LGA have been destroyed since the cycle of violence, often referred to as “farmers-herders clash”, began in 2001, according to Irigwe Youth Movement, a local youth organisation. HumAngle could not independently verify these figures.

‘Land at the heart of attacks’

“At the centre of the conflict in Plateau State is the issue of land,” said Nandi Helen Dale, an Information, Counselling, and Legal Assistance (ICLA) Officer at the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) Nigeria, Jos Area. The state government and local leaders hold the same view. “The assailants kill people, drive them away, and take over the land,” said Musa Ashoms, former commissioner of information and now youth development commissioner.

Governor Caleb Mutfwang disclosed in April that about 64 communities across hard-to-reach communities within Bassa, Bokkos, Mangu, and Riyom LGAs have been taken over and renamed by terrorists. HumAngle confirmed the dispossession with a local source in Bokkos earlier this year.

Analysts note that while land is at the core of the conflict, it often intersects with ethnicity, politics, and even religion, compounding tensions and making resolution elusive.

The result has been death and widespread displacement. Within three months in 2023, over 18,751 people were internally displaced and housed in 14 camps across Plateau State, with many more living with relatives or friends, according to Gideon and Funmi Para-Mallam Peace Foundation, a Jos-based humanitarian organisation. While some remain displaced, others, like Sarah and her family, have chosen to return and rebuild, despite the risks.

Returning home, however, does not guarantee security of land, most of which was inherited. These farmers lack formal documentation, relying instead on cactus fences, stones, or oral agreements scribbled on scraps of paper. This makes them vulnerable not only to violent dispossession but also to losing land in disputes with neighbours or relatives. Without proper documents, even a farmer who has tilled a plot for decades can be pushed aside.

Nigeria’s Land Use Act of 1978 recognises “rightful ownership” only through statutory or customary rights of occupancy, usually backed by a Certificate of Occupancy (C of O) or a customary C of O. Sarah, like many farmers who spoke to HumAngle, said she never even considered applying for the documents. Another farmer said he once thought about it, but the cost and bureaucracy discouraged him.

‘The papers bring hope’

In 2021, the Norwegian Refugee Council, with funding from GIZ, as part of its ICLA intervention, launched a project to help local farmers in Plateau State obtain land tenure documents and other identity documentation, such as birth certificates and national identity numbers.

“When we noticed the issues around forced eviction and displacement, we thought to intervene, since it aligns with one of our core competence areas,” Nandi said.

According to her, the process unfolds in stages. It starts with information sessions in rural communities, explaining why land documentation matters. Afterwards, the team provides counselling to identify individuals or households in need. This is followed by due diligence, often carried out in collaboration with traditional rulers, to confirm ownership.

“As part of the project, we signed a memorandum of understanding with government agencies such as the Ministry of Lands, Survey, and Town Planning,” Nandi said. “Once the due diligence is done, government surveyors come in to survey the lands, and thereafter, documents are issued. More of what we do is to facilitate access for these communities and also fund the entire cost.”

The project has run through two phases, enabling over 2,000 farmers across seven LGAs (Barkin Ladi, Bassa, Bokkos, Mangu, Riyom, Shendam, and Wase) to obtain land tenure documents.

For all the farmers who spoke to HumAngle, the papers have brought relief. “Now I know that no matter what, the land remains mine, and it will be there for my children and grandchildren,” Sarah said, while one of her grandchildren played at her side.

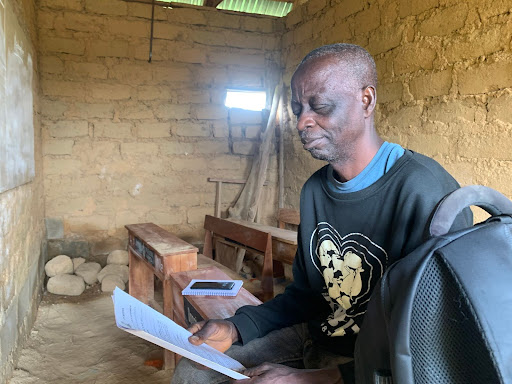

Others share similar feelings. In Nkienzha community, Bassa LGA, Jonathan Gihlah was able to register 1.371 hectares of land. Until then, he relied only on cactus markers and oral agreements to lay claim. “I have experienced trespassing several times,” he said. “One time, I fled due to the attacks. When I returned, I could only get three bags from my maize farm that usually gives me about 35 bags per harvest.” Without his new papers, he believes the land might eventually have slipped from his family’s hands.

In nearby Apasho village, 60-year-old Barnabas Trah said the documentation gives him both leverage and peace of mind. “Even if the government needs to use the land, I can easily present the documents to get compensation. Overall, it is the security it gives me. Without the paper, there will even be internal disputes on land sometimes,” he added, staring at his documents.

Traditional leaders also see change. Musa Zahwuie, the District Head of Te’egbe-Nkienzha, in Bassa, said, “The land documentation efforts have given our community hope. Families now have C of O, which has reduced [the risk of] land disputes and enabled displaced people to return with a sense of security.”

Nandi said implementing the interventions has been rewarding, especially with the assurance of ownership that the farmers now have. “Initially, when the first phase of the ICLA intervention started, some locals were hesitant, but through continued information sessions, they saw the need,” she told HumAngle. “Enrollment increased over time.”

But challenges remain. The process is costly, and funding for the project is running out; therefore, there will not be a phase two, meaning that other farmers who would have benefited would not. Also, the papers cannot stop bullets. “One time while registering farmers, we started hearing gunshots nearby,” Nandi recounted.

Communities in Plateau continue to face deadly attacks. In April, around 52 people were killed in an overnight raid on Zike, a village in Bassa LGA, barely 15 minutes from where HumAngle interviewed some of the sources for this story. A few months later, in July, 27 people, mostly farmers and their children, were killed in Riyom. Similar attacks have been reported in other areas, particularly in locations where the ICLA intervention is being implemented.

For these farmers, the documents offer hope, but not the safety of life. Land papers may secure their claims in law, yet whether they can shield their fields from violence remains an open question with every planting season, when the attacks are at their peak.

While projects like NRC’s ICLA have stepped in to help farmers secure formal land documents, government policy has also sought to curb dispossession. In 2020, the Plateau State government enacted the Anti-Land Grabbing Law to address the persistent problem of forceful evictions. However, implementation has been slow, leaving many farmers vulnerable. Recently, during a meeting with committees on the Resettlement of Internally Displaced Persons and Land Administration, Governor Mutfwang reaffirmed his commitment, stating that his administration will work diligently to enforce the law and protect landowners’ rights.

“I really hope that all of this will come to an end,” said Barnabas, who has lived his entire life in the community and has no desire to relocate. “This is our land.” Back in DTV, Sarah continues to farm with the help of her children. She keeps her land documents in the safest place she can find, a small gesture that carries the weight of her family’s hope for security and belonging.

In 2021, Sarah Ishaya's rural home in Plateau State, Nigeria, was attacked, endangering her sons and leading her family to flee temporarily.

Their house was burnt down, and recurring violence has deeply affected local farmers, termed as the “farmers-herders clash,” resulting in massive farm loss and displacement.

The core issue centers around land ownership disputes, exacerbated by ethnic and religious tensions, leading to widespread displacement, with over 18,000 people affected in three months in 2023.

In response, the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), funded by GIZ, has facilitated land documentation for over 2,000 farmers through its ICLA intervention, providing crucial security despite persistent violence.

This initiative, supported by the Plateau State government's Anti-Land Grabbing Law, aims to protect farmers' rights and ease land disputes, although implementation has been slow. Despite having land tenure documents, farmers like Sarah face ongoing security threats due to continued attacks, underscoring the complex dynamics of land ownership and safety in the region.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter