No Way Home: Satellite Images Reveal Dozens Of Towns Destroyed By Boko Haram Conflict

HumAngle has discovered over 200 towns, hamlets, and villages in Nigeria’s Borno state destroyed due to the ongoing insurgency. Reconstruction efforts by the government in some of the places have faced resistance.

Tunbun Buhari was once a lively town with a network of dirt roads, hundreds of homes and public buildings.

If you wind Google Earth’s satellite imagery back to 2010, you can see the village on an island in Lake Chad. But the up-to-date imagery shows nothing but rubble and the faded outlines of ruined homes.

Scrolling through the various updates between then and now shows how, little by little, the town fell to pieces after the Boko Haram insurgency reached the area.

The lives and livelihood of the residents were dependent on the waters of Lake Chad that surrounded the village. The people who lived there were fishermen and farmers. They settled in a part of the island that did not submerge during occasional rises in the volume of water. It had trees, which provided shade from the harsh sunrays and ensured the island was not washed away by the occasional flash flood.

In 2015, several buildings on the island disappeared. It is unclear what happened, but it coincides with the period of a significant military counter-offensive against Boko Haram. The terror group had captured towns and villages as it swept through the region.

The changes and widespread destruction in Tunbun Buhari became more evident in Dec. 2018. There were fewer structures and thick vegetation. The presence of earth roads, however, indicated human activity within the island and movements to nearby islands via paths along the marshland.

The number of visible buildings further declined by Nov. 2019, although there were new shelters at the southern tip of the island and in another location where boats would be observed in satellite images from Feb. 2o2o. Several boats also appeared at the entrance of a nearby waterway in Nov. 2022.

HumAngle’s months-long investigation has identified 221 hamlets, villages, and towns that were destroyed and, in some cases, totally overgrown by vegetation, almost wiping them from existence. Several other settlements were partially destroyed, due to the violence.

These destructions contributed to the displacement of thousands of people in Borno, the epicentre of the crisis. In 2017, an official of Borno disclosed that about 1 million houses and public structures were destroyed, estimating the value of the destroyed properties at the time to be over ₦1.9 trillion.

More towns becoming history

To the south of Tumbun Buhari is the island of Alinna Maimasallachi, located near the canal feeding the South Chad Irrigation Project of the Chad Basin Development Authority (CBDA).

In Dec. 2018, some of the island’s buildings were damaged. Three years later, the destruction spread significantly. Images taken in 2022 showed shelters amid thick vegetation had grown over the buildings.

A pattern of structures appeared close to the destroyed communities. The rise of water levels in Lake Chad also caused some of the newly built enclaves to sink. By the time the water receded in Feb. 2022, the settlements were gone. The location would be submerged again, as images from Nov. 2022 showed.

HumAngle’s survey showed there was growth in some places too.

On the other side of the canal is the island of Abuja, which held a small settlement that was destroyed in Dec. 2018. However, in 2019 shelters popped up where the ruins of the old community lay and expanded significantly up till last November.

HumAngle could not confirm if civilian returnees or insurgents were behind the construction of these new settlements. A vital insight into the population dynamics is from military briefings. In 2022, boats and combat aircraft supported the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) soldiers to target camps in the area.

Nigerian and Chadian troops reportedly carried out clearance operations in Tumbun Buhari and Tunbun Abuja in May. The soldiers also raided other island and shore communities, during which they arrested about 30 young men in the general area of Doron Naira. The men were said to have told authorities they were fishermen and farmers.

This indicates the presence of civilians seeking livelihood opportunities or living in these communities outside the control of the government. The availability of natural resources such as water, fish, and lush vegetation makes it attractive for the insurgents, economic migrants, and local inhabitants.

Also, in 2011, Metele was a vibrant town with a healthcare facility and a six-block U-shaped school in its southwestern corner.

In Aug. 2018, it looked like a disaster had occurred. Buildings were damaged, including the school. The magnitude of the destruction was pronounced. In November only one building still had a roof. It corresponds with the deadly attack on soldiers in the town.

An image from 2020 showed the surviving roof was gone and the school flooded. In early 2021, the school compound in Metele town likely appeared in an ISWAP propaganda video on child soldiers. It showed an execution that occurred in front of a pond and building with an “ETF 2007/2008 PROJECT” inscription.

The sign is used to indicate refurbishment or construction by the Education Trust Fund (ETF). OSINT analyst Tomasz Rolbiecki was able to connect the dots using data from the ETF 2008 file for projects and the distinct geographical features at the location.

Interactive dashboard map showing identified coordinates of abandoned towns.

Reconstruction efforts

Some communities that suffered varying degrees of destruction have undergone some level of reconstruction as part of the Borno state government’s resettlement efforts. At the same time, others have remained no-go areas due to the security risk.

One such no-go area is the town of Kerenoa (also spelt Kirenowa) which hosts the principal pumping station for the irrigation project. In 2013, Channels TV reported a military operation against Boko Haram in the town and captured the experience of locals under insurgent occupation.

A satellite image from 2015 showed developments in the town and public amenities, including a school, market, motor park, and a bridge across the water canal. But in Nov. 2016, the channel dried up, and some structures had become roofless. The scale of the destruction increased rapidly as more buildings became difficult to observe, especially in 2022.

According to an April 2022 briefing by the MNJTF, the town was part of the areas where troops conducted clearance. In January, a 48-year-old displaced person from the town, Umar Mustapha, spoke to HumAngle about his inability to return after the authorities closed the camp in Maiduguri where he was seeking refuge.

“It is a good thing that at least one is relocating from a camp far away from home to one near home, but what difference does it make? We are still going to be confronted with the same problems, if not worse than what we have suffered here in the last eight years,” lamented Mustapha. He was part of a group of displaced persons moving into camps in New Marte, located a few kilometres from Kerenoa.

New Marte has been the focus of the government’s efforts to resettle thousands of displaced persons. The town has also experienced intense fighting between the military and insurgents. In Jan. 2021, the town and military base was overrun in a raid. However, it was subsequently recaptured following a directive from late Army Chief Ibrahim Attahiru.

New Marte quarters suffered destruction as of Nov. 2016. In 2020, signs of rebuilding were visible, including a blue roof and trench alongside a second trench for the army base. It corresponds with the first phrase of resettling 500 households in the last quarter of 2020.

In 2021, dozens of shelters in two camp-like settings emerged, while in 2022, the main quarters appeared to have been refurbished. The shelters were also not dispersed but located near each other in what is likely a security measure.

Although civilians and the military had a presence in New Marte, the old Marte town is considered highly risky despite its potential utility as an agricultural hub. In Dec. 2016, roofless buildings appeared, and vegetation was visible at the local hospital.

The deterioration continued, and in 2018, some of the classes in what was likely the main school lost their roofs. By 2020, the grass had taken over a lot of places following the degradation of the town, with few structures still standing, like the big mosque in the middle of the town.

The absence of full state authority in Marte has national economic repercussions, particularly the decline in producing economic crops such as rice and wheat. Last year, the former executive director at Lake Chad Research Institute, Oluwasina Olabanji, noted that the local government area, which grew wheat on a large scale before, is now a no-go area because of the insecurity.

His comments align with the concerns raised by the then Director of the CBDA, Garba Abubakar Iliya, in 2013 about the threat insurgents posed to thousands of farmers in the area.

The pace of reconstruction has also varied from one community to the other, especially in large towns. For instance, authorities have made significant progress with the reoccupation of Baga, unlike Mallam Fatori.

In Jan. 2015, Boko Haram raided Baga and its environs, causing large-scale destruction and the death of over 2,000 people. Human Rights Watch reported that an earlier military raid in April 2013 resulted in the killing of residents and the deliberate destruction of property.

Satellite images confirm reconstruction has taken place over the past years. The state Attorney-General, Kaka Lawan, also said in a recent interview that the government had built and distributed over 200 permanent houses in Baga. “We have also constructed schools and other basic social amenities across Doron Baga and Cross Kauwa, as well as returned dwellers to their homes,” he mentioned.

Recent satellite images show the presence of civilian and military-type boats in the navy outpost in Baga, which had been expanded with reinforced security. It was previously abandoned after the 2018 ISWAP incursion.

The situation in Mallam Fatori is much more different and delicate due to persistent insurgent threats. The area has been in and out of government control; it was recaptured by regional multinational forces from insurgents in 2015 and then again in 2016.

Since then, the military has occupied the town. Meanwhile, 4,000 Nigerian refugees residing in the Bosso area of Niger’s Diffa region were resettled there between March and April 2022. They were kept in temporary shelters in the town after authorities had conducted some level of work on facilities.

The temporary camp was flooded last year, and casualties were recorded after insurgents attacked it. In April, governor Babagana Zulum visited. He was quoted as saying his visit was to assess the clearance process and prospect of returning locals. “We want the people to return next month [May] for normal activities to return to this part of the state, insha’Allah,” he added.

Several communities in other parts of Borno were also affected, particularly those within and near the insurgents’ Sambisa and Alagarno forest strongholds. An example is the town of Kafa, located around a stretch of highly contested land in Borno and Yobe, known as the Timbuktu Triangle.

Kafa was a ghost town with relics of buildings in the most recent satellite image taken in Feb. 2021. The only signs of human activity were the nearby dirt roads and a Forward Operating Base (FOB) built between Sept. 2019 and early 2021 to support counter-insurgency operations.

Google Earth last captured the area as densely populated in Nov. 2013, showing buildings and farmlands. The next capture in May 2018 showed the town’s almost apocalyptic destruction.

About 8 kilometres away is a smaller community, Kafa Mafi, also noticeable in 2013, though the roofs of a school-type compound had vanished. In 2018, most of the buildings were destroyed, and in 2022, the entire community was largely gone except for the remains of the structures.

Although insurgents are mostly blamed for the destruction of communities, it’s highly possible some of it was a result of military action.

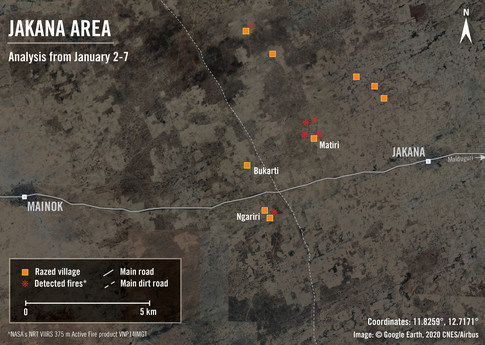

Amnesty International in 2020 reported that the military burned and forcibly displaced villages in response to an escalation in insurgent attacks. The human rights body revealed satellite imagery showing the burning of Bukarti, Ngariri, and Matiri villages near the Maiduguri-Damaturu road.

This report contains satellite imagery sourced from Google Earth Pro and Earth Studio. Image analysis and illustrations were conducted by HumAngle.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter