Nigeria’s Resurging Terror Attacks Amidst Global Displacement Crisis

The 2024 global internal displacement figures are chilling, and Nigeria sits as the fourth country with 3.7 million IDPs in Sub-Saharan Africa. Without a responsive strategy, experts say the resurgence of ISWAP/Boko Haram’s coordinated attacks could further exacerbate Nigeria’s internal displacement crisis.

The recent Global Report on Internal Displacement (GRID) published by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) paints a troubling picture: worldwide, there are now 83.4 million internally displaced persons (IDPs)—a sharp increase from previous years.

A significant number of these displaced persons, nearly 90 per cent, or 73.5 million people, were displaced by conflict and violence, an increase of 80 per cent in six years. Ten countries had over 3 million IDPs from conflict and violence at the end of 2024, double the number from four years ago. Sudan alone hosted a record-breaking 11.6 million IDPs, the most ever recorded in a single country.

Conflicts resulted in 20.1 million new displacements, while disasters accounted for 45.8 million globally. This escalation highlights the growing humanitarian challenge facing displaced communities, governments, and humanitarian actors.

“Internal displacement is where conflict, poverty and climate collide, hitting the most vulnerable the hardest,” said Alexandra Bilak, IDMC’s director. “These latest numbers prove that internal displacement is not just a humanitarian crisis; it’s a clear development and political challenge that requires far more attention than it currently receives.”

In most cases, many had to flee multiple times throughout the year, especially as conflict areas changed. This situation has impacted their vulnerabilities and impeded their efforts to rebuild their lives. The Democratic Republic of the Congo, Palestine and Sudan reported 12.3 million internal displacements, or forced movements of people, in 2024, nearly 60 per cent of the global total for conflict displacements.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, over 11 million people were displaced by conflict and violence, while about 8 million were displaced by disaster in 2024, representing 29 per cent of the global figure.

This year’s figure brings the number of internally displaced people in Sub-Saharan Africa to 38.8 million, a 47 per cent share of the global total. Sudan tops the chart with 11.5 million internally displaced people (IDPs), the most ever for one country.

Other countries with high records are the DR Congo [6.8 million], Somalia [3.8 million], Nigeria [3.7 million], and Ethiopia [3.1 million].

In 2022, the United Nations Secretary-General, António Guterres, launched a global Action Agenda on Internal Displacement to address the escalating number of people forced from their homes due to conflict, violence, disasters, and climate change. The agenda focused on three interconnected goals: helping IDPs find durable solutions, preventing future displacement crises, and ensuring adequate protection and assistance for those affected.

In the action agenda, Guterres emphasised the urgent need for integrated solutions that combine development, peacebuilding, human rights, and disaster risk reduction efforts. The action plan recognised that displacement cannot be resolved without addressing its root causes and called for greater collective action to ensure long-term stability for affected populations.

Incidentally, considering the latest global figures, it has been inconsequential.

Displaced by conflicts

Nigeria’s displacement crisis has persisted for decades, with both conflict and climate factors playing a crucial role. A home to 3.7 million IDPs, Nigeria sits as one of the hardest-hit countries in Africa.

In 2024 alone, new conflict-related displacements were heavily concentrated in Sudan and the DR Congo, alongside enduring crises in Palestine, Syria, Yemen, and Ukraine. In Nigeria, however, conflict remains the leading driver of forced migration, as civilians flee violence and insecurity.

Decades of armed conflict in the northeast, rural banditry in the northwest, environmental disasters, and communal clashes in the north-central continue to drive displacement across the country, reflecting global trends.

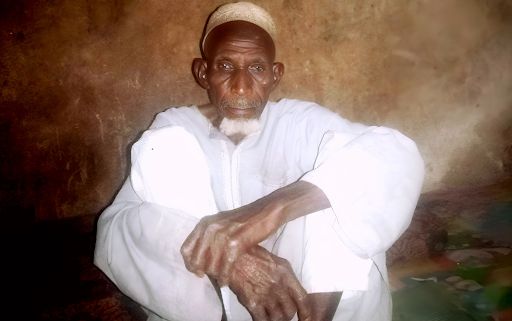

68-year-old Abdulrahman Yusuf, a visually impaired man whose life has been altered by violence, is one of the 3.7 million displaced persons in Nigeria.

Once a proud farmer in Tsabare, a village in Zamfara State, North West Nigeria, Yusuf knew the land by touch rather than sight. Despite being visually impaired, he cultivated his fields with the support of his children and hired labourers, tending to the earth that had sustained his family for generations.

The relentless wave of terror that swept through Tsabare and much of Zamfara State forced Yusuf and countless others to flee. No longer a farmer, no longer a man with land to call his own—he became displaced, forced to beg for survival, his dignity eroded by violence and fear. His fields now lay abandoned, his community scattered, and his home reduced to memory.

“If our hometown were peaceful, we would return immediately. Farming is all we know. But they won’t let us live—they seize our crops, invade our homes, and kill at will,” he told HumAngle.

Yusuf’s situation is not isolated. The insurgency by ISWAP/Boko Haram and other armed groups has continued to displace several others, like Fanne Goni, in the country’s northeast.

For more than a decade, displacement had shaped every corner of Fanne Goni’s life. At 63, she carried the scars of exile, longing for the stability that had eluded her family for years. In 2019, when the Borno State government announced the resettlement of displaced households to Kawuri—her long-lost hometown—she dared to believe that, finally, they could reclaim the life they once knew. Reality proved far harsher.

By November 2024, Kawuri had become unlivable again. The spectre of insecurity loomed large, hunger gnawed at the people, and the ever-present menace of ISWAP/Boko Haram made the act of daily survival nearly impossible. Hope, once fragile, shattered completely. Families abandoned their homes one by one, slipping away in silence, seeking safety wherever it could be found.

Fanne’s family joined them.

In the dead of night, they fled Kawuri for Dalori, a village near Maiduguri. Their return to Kawuri had felt like an attempt at restoration, but it became clear—it was not a return at all. It was just another cycle of displacement, another chapter of uncertainty.

“We returned to Kawuri, but nothing worked. We were forced to leave again,” Fanne told HumAngle, her voice carrying the weight of disappointment.

Kabiru Adamu, the Director of Beacon Security and Intelligence, a risk management and intelligence provider focused on Nigeria and the Sahel region, told HumAngle that the authorities’ inability to implement an effective measure for documenting this movement is a serious concern.

“It’s very rare that you have these movements documented,” he noted. “You hear denial or, in some instances, attempts to block news of these movements. The reality is that it is happening.”

Disaster-induced displacement

The GRID report indicates that environmental disasters are accelerating displacement. Climate change-related extreme weather events, including floods, droughts, and wildfires, have displaced millions across Asia, Africa, and the Americas.

In addition to conflict-driven displacement, nearly 9.8 million people were displaced by natural disasters globally in 2024, an increase of 29 per cent from the previous year.

According to the IDMC report, over 1.2 million people had been displaced in Nigeria as of 2024. These disasters, in the form of severe floods, particularly affected communities along the Benue and Niger River basins. Extreme rainfall has also displaced millions of Nigerians, destroying homes and farmland, forcing entire communities to relocate.

Nigeria has implemented various policies to address displacement, like the National Policy on IDPs, which aims to provide durable solutions like resettlement and reintegration and investments in climate adaptation programmes to mitigate disaster-related displacement. However, it has yet to mitigate the displacement crisis in affected parts of the country.

However, humanitarian leaders have voiced urgent concerns over the growing crisis. Jan Egeland, Secretary-General of the Norwegian Refugee Council, stressed the need for immediate global intervention.

“Internal displacement rarely makes the headlines, but for those living it, the suffering can last for years. This year’s figures must act as a wake-up call for global solidarity. How much longer will the number of people affected by internal displacement be allowed to grow due to a lack of ownership and leadership?” Egeland said.

The Secretary-General noted that ongoing cuts in humanitarian funding exacerbated the crisis: “Every time humanitarian funding gets cut, another displaced person loses access to food, medicine, safety, and hope.”

“The cost of inaction is rising, and displaced people are paying the price. The data is clear; it’s time to use it to prevent displacement, support recovery, and build resilience,” IDMC’s Director, Alexander Bilak, added.

A cause for alarm?

Recently, Nigeria’s northeast has witnessed a troubling resurgence of attacks by Boko Haram and ISWAP. These militant groups have intensified their operations, targeting military bases, civilians, and critical infrastructure. The extremist groups have escalated their operations, deploying drones and satellite technology to strike communities and military outposts.

Borno State Governor, Babagana Zulum, has voiced concerns over the renewed wave of violence, warning that the state is losing ground in the fight against insurgency. Locals have echoed these fears, noting that attacks are occurring almost daily, with abductions and killings becoming more frequent.

In response to the recent surge in terrorism, particularly in the northern region and other flashpoints across the country, President Bola Tinubu has since directed the service chiefs to review and implement new security strategies to put an end to the situation. Also, the president has equally approved the procurement of advanced air assets and security equipment to strengthen counterinsurgency efforts.

However, this resurgence has raised alarms about the fragility of security efforts in the region, with experts warning that the groups are becoming more sophisticated in their operations. The situation remains dire, with communities struggling to cope with the renewed violence and displacement.

Between May 12 and 13, HumAngle reported how a coordinated wave of violence by the Islamic State of West Africa Province [ISWAP] raged through Borno State in northeastern Nigeria. The offensive, which targeted rural communities like Marte, Dikwa, Rann (Kala-Balge LGA), and the Damboa–Maiduguri road in near-simultaneous strikes, signals strategic coordination, technological evolution, and growing audacity.

Terrorists have resumed using IED explosives on strategic routes that serve as a lifeline for economic activities in the southern part of Borno. Recently, along the Maiduguri-Damboa Road, an IED explosion claimed the lives of two education workers and several civilians, further highlighting the insurgents’ use of unconventional warfare.

Security experts have warned that increased attacks could further exacerbate the conflict and violence-related displacement crisis in the country.

Kabir says insecurity, especially the attacks by non-state armed groups in different parts of the country, is leading to increased displacement, and without adequate public security in areas that are being attacked, it results in displacement.

“There were a series of attacks in Marte, and we monitored the movement of several displaced persons from Marte to other locations, including Dikwa and Gwoza. So it’s very clear that attacks by ISWAP and Boko Haram are increasing the number of displaced persons within the country,” he said.

“We are also monitoring the same in the northwest in places like the Tsifa Local Government Area in Sokoto State, where non-state armed terrorists like Bello Turji and his associates are present. We’ve observed several villages being displaced because of the constant pressure, including the collection of levies and attacks,” Kabir added.

The resurgence of Boko Haram and ISWAP attacks also underscores the unending security challenges in northeastern Nigeria, which can negatively impact the current displacement figure. Urgent and practical actions to mitigate the internal displacement crisis in the northern region are needed.

“Now, we don’t know if it will increase; we hope it won’t, given that we’ve heard two presidential directives, including one on May 16, when the president met with the security chiefs to end the insurgency. But the more attacks by non-state armed groups, the more displacements there will be,” Kabir emphasised.

The Global Report on Internal Displacement by the IDMC reveals a significant rise in internally displaced persons (IDPs), reaching 83.4 million worldwide due to conflicts and disasters.

Conflict accounted for 73.5 million displacements, with countries like Sudan, DR Congo, and Nigeria heavily affected. Meanwhile, 45.8 million were displaced by disasters, predominantly driven by climate-related events, emphasizing a critical humanitarian, political, and developmental challenge.

International leaders and humanitarian agencies stress urgent intervention, as current efforts, such as the UN's Action Agenda, have proven insufficient. Nigeria's situation remains dire, facing persistent displacement due to ongoing conflict and environmental crises, with government policies like the National Policy on IDPs failing to mitigate the growing crisis. Recent violent resurgences by militant groups like Boko Haram and ISWAP further exacerbate the displacement challenge, highlighting the need for strategic planning and increased security measures.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter