Nigeria’s Policing Crisis: A Role Lost to the Military

The police are outnumbered, soldiers are overstretched, and the public is caught in a dangerous power vacuum fueled by institutional disarray and the quiet erosion of civil liberties.

From camps in Borno to street corners in Jos or online forums in Lagos, Nigerians are asking the same question: “Who’s responsible for our safety?”

It echoes louder each time a village is attacked, a school is shut, or families are forced to flee again. The country is replete with soldiers and police checkpoints. A new special task force is formed frequently. Yet, the violence continues.

Across the North East, insurgents wage a relentless campaign, displacing communities and destabilising entire regions. Separatist agitation is volatile in the South East, feeding unrest and confrontation. The North West is plagued by the kind of terrorism that blurs the line between ideological violence and organised crime, while the North Central battles a dangerous mix of terrorism and sectarian conflict.

In Nigeria’s commercial centres, violent crime festers, expressing itself through kidnappings, cult clashes, and armed robbery that no longer respect time or place. Each is complex, rooted in history, grievances, and deep socio-economic fractures. Though different, they all persist, grow, and adapt despite the government’s multi-pronged security interventions. For every new strategy launched or force deployed, the violence seems to morph and resurface elsewhere, often with greater ferocity.

The military’s grip on internal security

Nigeria’s reliance on the military for internal security is not new. A retired Assistant Inspector-General of Police (AIG) notes it began during the military era, when armed forces sought visibility and influence, often at the cost of the police.

Brigadier General Saleh Bala (rtd.), a veteran of many military campaigns and the president of White Ink Institute, provides deeper historical context. He links the military’s domestic role to the post-colonial period, particularly the Tiv riots and Operation Wetie in the Western Region. Even then, while police retained the lead, the military’s active support gradually expanded.

According to Bala, the real shift occurred post-civil war, with surging armed robbery in urban areas during the era of notorious figures like Oyenusi and Anini. The police’s inability to match this threat due to outdated equipment, low morale, and inadequate training enabled the military’s growing internal role. This, he says, was cemented further after the 1983 coup, where regime protection became paramount following attempts by then Inspector General of Police (IGP) Sunday Adewusi to thwart the coup.

These developments paved the way for the military’s sustained involvement in internal policing through state-led operations like “Operation Sweep” under General Buba Marwa, which set the template for numerous state-level joint task forces today.

The AIG remarks, “The result was that the police were denied funding for equipment and training, lost morale, and slowly withdrew.” Bala adds that while military interventions initially curtailed violent crime, overexposure led to diminishing professionalism and allegations of abuse similar to those levied against the police.

Soldiers as police: a reversal of roles

Today, soldiers respond to crime scenes, enforce curfews in peacetime cities, and patrol highways. The line between policing and military duties has blurred, with the military often serving as the de facto internal security force.

Bala agrees with this description but clarifies, “The military does not assume this role unilaterally. It acts only when requested by civil authorities and sanctioned by the President through the National Security Council.” He emphasises that this support role is constitutional and subsidiary, designed to help the police regain control and hand over post-stabilisation.

Where the AIG sees erosion of roles, Bala sees the outcome of evolving threats, particularly hybrid threats like Boko Haram and multi-layered terrorism, that overwhelm police capacity. However, both agree that the police must be revitalised to regain primacy in internal security.

Policing the elite, not the public

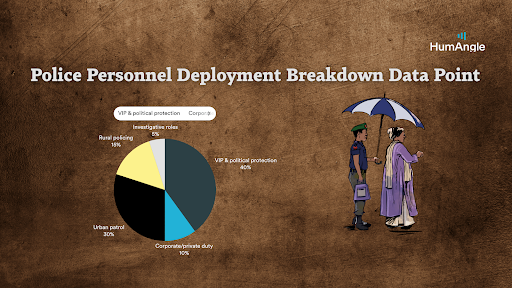

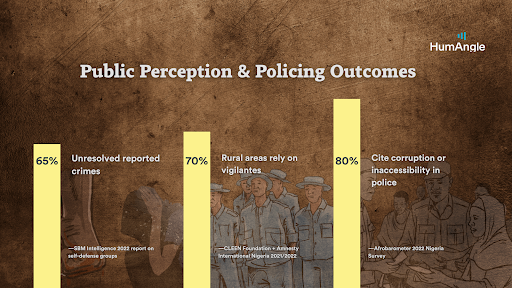

The CLEEN Foundation and a number of other civil society organisations in Nigeria have written extensively on the drift from securing the nation by the police to a troubling focus on protecting VIPs, in addition to widespread corruption and low faith in the police institution.

The AIG points out a disturbing trend: officers cluster around VIPs, leaving ordinary citizens exposed. This elite capture of police services, coupled with a dismal police-to-citizen ratio in most African countries, including Nigeria, undermines the safety and security of citizens.

Brigadier General Bala refrains from directly challenging this critique but shifts focus toward the need for the police to “rise above their preference for soft, high-profile urban operations.” He urges a move toward rural policing and special operations, citing international examples where law enforcement operates capably across diverse terrains.

He stresses political leadership as the driver of such reform: “The police need political direction to prioritise nationwide security expectations over elite security needs.”

Too many uniforms, too little coordination

HumAngle has, over the years, documented Nigeria’s bloated security environment, in which the DSS, NSCDC, Immigration, Customs, and other agencies frequently act in opposition. Intelligence is delayed, mandates are unclear, and many outfits lack focus.

The AIG calls for streamlining, suggesting that the DSS return to its 1980s and 1990s focus on community-centric intelligence gathering, while the NSCDC personnel be redeployed as a foundation for state police. Many analysts offered similar advice for merging vigilantes and dozens of self-help militias across the country into the NSCDC and maybe decentralising this outfit into regional police, rather than each state in Nigeria having semi-autonomous or independent security force.

“Rather than 36 separate police entities, we should have regional police that are in line with Nigeria’s six geographical zones,” a top police officer in Abuja said, adding that if state-based police institutions are adopted, governors who already have authority over local government administration “will muster too much power.”

The crisis of imagination

The AIG argues that Nigeria’s insecurity stems from a flawed belief that force alone ensures safety. Instead, he champions investigative policing, forensic tools, training, and direct departmental budgeting.

Bala provides a broader context: “Warfare itself is now institutionally all-encompassing. Security threats are increasingly urban and asymmetric. Policing must now be part of a whole-of-government, all-of-society approach.”

He warns of the “militarisation of all security forces” due to adversaries’ tactics. He draws attention to advanced democracies where police forces are as capable as some militaries. This, he suggests, should inform Nigeria’s transformation: building police forces that are not only community-responsive but also operationally hardened.

Restoring trust, rebuilding institutions

The AIG proposes revamping police colleges in Ikeja, Kaduna, and Maiduguri into detective hubs. He calls for merit-based recruitment and unassailable discipline to restore legitimacy.

Bala doesn’t directly oppose these views but reiterates the need for synergy: “Military, intelligence, law enforcement, and paramilitaries must become domain-specific specialists who can adapt across blurred threat boundaries.”

Both agree that trust in the police can only be restored through professionalism, neutrality (especially during elections), and effective public service—not militarisation.

Towards a new vision

Nigeria stands at a crossroads. Its current security model, built on elite protection and military overreach, is unsustainable. Both Bala and the AIG call for a pivot towards decentralised, professional policing, political will, and community-grounded justice.

Bala underscores the need for coherence: “The answer lies in orchestrated cooperation. Security cannot be left to force projection alone. It must be institutional, strategic, and inclusive.”

In a country overwhelmed by uniforms, one truth endures: security is not guaranteed by presence, but by purpose. And that purpose must be justice.

Nigeria faces a critical policing crisis, with military overreach filling the void created by an underfunded and demoralised police force, leading to a dangerous power vacuum and ongoing violence. Reliance on military for internal security traces back to post-colonial times and heightened after the civil war, resulting in blurred lines between policing and military duties. This trend has shifted focus from public security to elite protection, leaving citizens vulnerable.

Proposals to strengthen Nigeria's security focus on revitalising police roles and capabilities, enhancing professionalism, and ensuring community-rooted justice. Experts call for streamlined security efforts, regional police structures, and an inclusive approach that integrates military, intelligence, and law enforcement operations. Effective reform and political commitment are essential to transition from force-driven security to purpose-driven justice, fostering trust and institutional coherence.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter