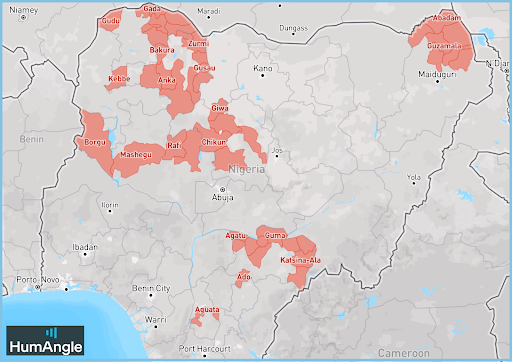

Nigeria’s Governance Gap Widens as Ungoverned Areas Multiply

Across Nigeria, sovereignty is unravelling, not just in theory, but in the lived realities of millions. From the floodplains of Lake Chad to the rainforests of the Southeast, the Nigerian state is in retreat.

The spate of insecurity in Nigeria is turning many local communities into ungovernable spaces. As the secular government withdraws from these communities, terrorist groups expand their influence, consolidate authority, and accumulate illicit wealth. Traditional leaders—once the primary link between the people and governance—now operate under the coercive control of armed factions, which have established parallel administrations and seized the reins of the local economy.

North East

The government’s absence is nearly absolute in northeastern Nigeria, around the Lake Chad basin. Here, the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) and remnants of Boko Haram terrorists operate not as fugitives but as rulers. Their authority is layered, structured, and chillingly effective.

ISWAP has organised its territory into mantikas (localities), which are regional districts aligned with Nigeria’s federal structure. These mantikas oversee taxation, zakat (alms-giving), farm levies, education (Qur’anic schools and ideological reprogramming), security, courts, and patrols.

Several communities in Abadam, Guzamala, Kukawa, Marte, and Mobbar no longer wait for state forces; they negotiate directly with insurgent-appointed administrators. The group’s brutality is, for many, accompanied by a disturbing sense of order within a context devoid of hope.

North West

While ISWAP’s rule is ideological, in North West Nigeria, it encompasses a chaotic mix of economic, ethnic, and religious factors. In Zamfara, armed groups now operate like proto-states. The forests of Maru, Bakura, and Anka are home to well-defended camps with command hierarchies, blood-draining tax systems, and armouries supplied via Sahelian trafficking routes and after raids on military positions.

HumAngle investigations found that communities like Tungar Doruwa, Maitoshshi, Chabi, and Kwankelai—once protected under the Dankurmi Police Outpost—are now under the firm control of Kachalla Black and Kachalla Gemu. Further south, Kungurmi, Galeji, and Yarwutsiya are governed by Kachalla Soja and Kachalla Madagwal. Up north, Kango Village and Madafa Mountain serve as fortresses for terrorists like Wudille and Ado Aleru, who command loyalty through a combination of fear and patronage.

Here, terrorism is no longer sporadic. It is systemic. It is territorial governance without borders, aided by the region’s gold trade, deep forests, and a broken justice system. Entire LGAs now function as autonomous war zones where Nigerian laws hold no sway.

The little-known Lakurawa terror network is enforcing a form of stealth insurgency in the areas of Isa, Sabon Birni, and Rabah in Sokoto State. Schools are shuttered, roads are mined, and civilians pay levies for survival. The group’s cross-border tactics, using the Niger Republic as a tactical fallback, make them elusive and resilient.

Many villages with large populations, like Galadima, Kamarawa, and Dankari in Sokoto, now survive on whispered warnings and ritual bribes. Lakurawa’s governance is less visible but equally firm, with taxation, curfews, and brutal retribution. Residents say sporadic military raids offer little relief; the terrorists return hours later, more vengeful than before.

The fractures in Kaduna State mirror the broader problems in Nigeria. In Chikun, Giwa, and Birnin Gwari, attacks by Ansaru factions and criminal warbands have pushed out state institutions. Southern Kaduna adds another layer, with ethnic violence fused with terror raids, leaving villages like Jika da Kolo and Tudun Biri in ruins.

Katari, once a symbol of Kaduna’s transport link to Abuja, is now a ghost zone, haunted by the memory of the 2022 train attack. Trains now pass, but the residents remain missing, displaced or dead.

North Central

In Niger State, rural districts like Shiroro, Mashegu, and Borgu are steadily slipping from state and federal control. After attacks such as the 2021 Mazakuka mosque massacre, entire villages fled, leaving behind ghost towns. ISWAP and affiliated terror cells have since moved in, using dense forests to launch ambushes and collect tribute.

In Rafi, Allawa, Bassa, and Zazzaga, residents speak of “government by gun”, which is enforced through nighttime raids and extortion rackets. What began as raids has metastasised into permanent displacement. Farming has ceased. Children grow up never having seen a police officer.

Niger State is next to Abuja, Nigeria’s federal capital territory.

South East

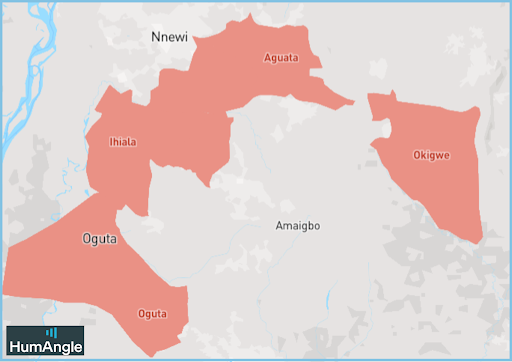

The secessionist group known as the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) has transformed parts of Imo and Anambra States into shadow states. What began as ideological agitation has evolved into fragmented shadow governance, particularly in Orsu, Oguta, and Nnewi South, where IPOB’s Eastern Security Network (ESN) now operates checkpoints, enforces lockdowns, and levies informal taxes. Police presence is almost nonexistent; courts are shuttered; schools function sporadically.

This pattern is not isolated. As Mgbeodinma Nwankwo reports for HumAngle in Onitsha, “Southeast Nigeria has greatly changed from a region with historical landmarks and trade centres to areas of gunfire that make life deadly for civilians and law enforcement officers.” States like Anambra, Imo, Abia, and Ebonyi have become centres for violence. Non-state armed groups routinely block roads and attack police stations. Businesses close early, travel routes are avoided, and fear governs daily life.

IPOB’s camps, hidden in forest belts, serve as training grounds and operational bases – funded by diaspora networks and sustained by black-market arms. The state’s coercive apparatus has collapsed in these ungoverned interiors, like Ihiala and stretches of rural Imo. Local vigilante outfits like Ebube Agu and Operation Udo Ga Chi strive to maintain a fragile order, often overwhelmed by better-armed non-state actors.

As Nwankwo describes, uniforms have become “magnets for attacks.” Police and military personnel are hunted, ambushed, kidnapped, or executed. One soldier, attending a party in Imo while off duty, was identified and found dead the next morning.

“Wearing a uniform here is like painting a target on your back,” said a police officer in Imo, speaking anonymously. “We go to work in mufti and only change when necessary. Even then, we operate in groups, as solo patrols pose a significant risk.”

The psychological toll is immense. Morale among security forces is at an all-time low. Many seek transfers, and while some still consider the southeastern region postings financially rewarding, the life-threatening risks overshadow any incentives.

The violence is driven by a volatile mix: separatist agitation, criminal opportunism, and state withdrawal. IPOB and ESN are often suspected to be responsible for many of the terror attacks, though they frequently deny involvement. Criminal gangs, exploiting the chaos, further destabilise the region.

State response has focused on increasing highway checkpoints, leaving interior communities exposed. Critics argue this reactive approach exacerbates tensions. “Deploying more soldiers is not enough,” warns Dr Chioma Emenike, a conflict resolution expert based in the southeast. “There must be dialogue, economic empowerment, and trust-building between security agencies and local communities.”

Ultimately, the region faces a dual crisis of security and legitimacy. As uniforms vanish from the rural southeast, so does any semblance of state authority. What remains is a precarious state of fear and survival—residents trapped between hostile non-state actors and a disengaged state, teetering on the edge of anarchy.

Nigeria’s unseen frontlines

Nigeria’s forests have become its most telling metaphor. Once tourist destinations and biodiversity treasures, they are now frontlines of insurgency. No-go zones include Kamuku, Kainji, Falgore, and Sambisa. Dumburum and Kagara are insurgent capitals.

Even southern states are not spared. In Ondo, Edo, and Lagos, the forests harbour kidnappers and traffickers. In the Niger Delta, mangroves shelter oil theft rings bleeding billions from the national treasury.

These green belts mark the outer limit of Nigeria’s practical sovereignty. Beyond them lies another Nigeria: unrecognised, ungoverned, and rapidly growing.

Kabir Adamu, a seasoned security analyst and the CEO of Beacon Security and Intelligence Limited–a security risk management and consulting firm– expressed concerns over the scarce presence of governance and secular leadership in territories overrun by terrorists.

“Where they exist, they typically include poorly staffed and under-resourced police posts, non-functional or abandoned local government offices, dilapidated schools, and health and medical centres with little to no medical personnel or supplies,” he told HumAngle, noting that, in some locations, especially in northern Borno and remote areas of Zamfara and Katsina, such structures have been destroyed or taken over by terrorists, further eroding state presence.

Adamu added that, as the state recedes, communities have been forced to adapt in ways that challenge conventional notions of governance. He said many communities have resorted to local self-help mechanisms, including forming or reviving armed vigilante groups, with support from traditional rulers or local elites in some cases.

“These groups often serve as the first and only line of defence against armed groups, conducting patrols, manning checkpoints, and gathering intelligence. Unfortunately, the formation of the vigilantes continues not to reflect the communities’ diverse residents,” the security analyst noted.

Forest guard corps

The federal government’s response to these problems offers a glimmer of optimism, as it established the new Forest Guard Corps to reclaim these wild spaces. Trained in guerrilla warfare and intelligence, these units, drawn from local populations, are tasked with intercepting armed groups and restoring order.

However, without systemic reforms such as real policing, honest governance, and economic renewal, the corps risks becoming merely a temporary solution to a persistent problem. These affected communities nationwide need more than just soldiers; they need schools, courts, trust, and opportunities.

Although Adamu admitted that the Nigerian government has taken various actions in and around ungoverned spaces to reduce the influence of armed groups, he insisted that these approaches remain fragmented and often lack the institutional follow-through needed to fill the broader governance vacuum.

“There are clear signs that the ungoverned spaces in Nigeria are expanding, consolidating, and in some cases, connecting across local government and state boundaries in mostly the northern regions but also affecting some of the southern areas,” he said, adding that although military operations have resulted in the arrest or killing of militants, and recovery of weapons, the gains are often temporary in the absence of sustained civilian governance.

The rise of an economy of fear

As formal taxation collapses, ransoms rise in northwestern Nigeria. In Dansadau, HumAngle found that farmers trade goats and sorghum to retrieve kidnapped relatives. In Zugu and Gaude, families pay monthly levies to criminals to avoid attacks. Pay tribute is the only way to ensure public safety in some places.

A breakdown of ransom payments made in Nigeria between May 2023 and April 2024, according to the National Bureau Of Statistics: Infographics: by Damilola LawalThis economy of fear has reshaped entire communities. Young men, disillusioned and broke, join gangs and terrorist groups as an alternative to starvation. Each payment made strengthens the enemy and weakens the state.

In many rural communities, ransoms are paid in cash, livestock, or entire harvests. Local leaders admit to pooling security levies from residents to meet ransom demands — institutionalising these payments and strengthening the criminals’ hold.

“Displacement remains a widespread coping strategy; fearing violence or oppressive demands from armed actors, entire villages have fled to IDP camps or relocated to safer towns and cities, leaving behind homes and livelihoods,” Adamu stressed, confirming the overwhelming fear consuming locals in these communities.

“Others, unable or unwilling to flee, have turned to informal negotiations with insurgents or bandits — offering payments in cash, crops, or livestock in exchange for relative peace. In some areas, communities have adapted to insurgent-imposed governance systems, accepting taxation or dispute resolution by armed non-state actors to maintain a semblance of normal life,” he added.

This cycle of violence is self-sustaining. As armed groups become richer and better armed, their reach extends deeper into communities. Interviews by HumAngle revealed that young men claimed that they saw joining kidnapping gangs in the forests as their sole means of escaping the oppressive poverty they faced.

Every community across the country visited or examined by HumAngle reveals the same grim logic: when the state withdraws, someone else steps in. Whether they come in the name of religion, gold, or secession, these armed groups usurping Nigeria’s justice system are redrawing the country’s map from the grassroots up.

Nigeria is facing a severe security crisis, with many local communities becoming ungovernable. Insurgent groups like ISWAP and Boko Haram have taken over governance in areas such as the North East, establishing parallel administrations and economies supported by extortion and illegal activities. In the North West, armed groups operate as proto-states with elaborate command structures, and regions like Zamfara have become lawless territories where entire local governments function as autonomous war zones.

In areas like the South East, separatist movements such as IPOB have created shadow governments, disrupting normal life with checkpoints and informal taxes. The forests throughout Nigeria, once tourist attractions, are now insurgent strongholds and hubs for illegal activities, marking the limits of the state's sovereignty. The federal government's creation of a Forest Guard Corps aims to combat these issues, but without comprehensive reforms, it is likely only a temporary fix.

The prevalence of armed groups has fostered an economy of fear, where communities pay ransoms and tributes for safety, perpetuating a cycle of violence. These developments highlight the urgent need for effective governance, trust-building, and economic empowerment to restore stability and state authority across the nation.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter