Nigeria’s Frosty Interest In Private Military Contractors

Debates on bringing in foreign private security contractors often incite wild reactions, including from the military brass. However, such contractors are helping with filling capacity gaps.

Nigeria appears to have an appetite for foreign military contractors, but agreements with them are often limited to training and equipment support roles. It may be because this approach is associated with less political risk and international scrutiny unlike contracts involving field training and combat exposure.

The country has a complicated history with the use of foreign contractors (mercenaries) to build the capacity of the military, particularly as the government rolls out efforts to reverse counter-terrorism setbacks in the Northeast. This is despite concerns and the tense outlook towards their involvement.

In early April, Nasir El-Rufai, governor of Nigeria’s troubled northwestern Kaduna State, threatened to bring in foreign mercenaries to fight the terrorists hibernating in the forest areas, if the federal government failed to tackle the problem. The governor’s comment was triggered by recent attacks in Kaduna, including a deadly raid and abduction of passengers aboard a train moving from Nigeria’s capital, Abuja, to the state.

“I have complained to Mr President and I swear to God, if action is not taken, we as governors will take actions to protect the lives of our people; If it means deploying foreign mercenaries to come and do the work, we will do it to address these challenges,” El-Rufai was quoted to have said.

Although there are legal and political bottlenecks that make it difficult to see his statement as more than mere rhetoric, it spotlights the issues surrounding the military’s inability to subdue the violence in the north of the country.

A month earlier, in February, Babagana Zulum, the governor of Borno, the epicentre of the 12-year-old insurgency in the Northeast, reiterated his call for hiring mercenaries. The governor had made a similar recommendation in the past to reinforce the fight against insurgents, an approach that was used by Abuja under the previous administration. This proposal was also a subject of debate in the country’s lower house of parliament.

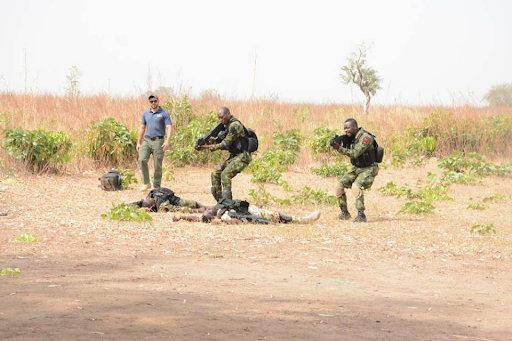

In late 2014, the former administration through the Office of National Security Adviser brought in South African private military contractors to train an Army unit in order to find and rescue the abducted Chibok Schoolgirls. However, the mandate subsequently transitioned towards filling counterinsurgency knowledge and experience gaps to support aggressive operations against Boko Haram.

The International Centre for Investigative Reporting (ICIR) in a 2016 report revealed that a team comprising about 147 mercenaries served between Dec. 2014 and April 2015. At least two of the contractors were said to have been killed during the assignment which involved three companies – Conella Services Ltd, Pilgrims Africa, and Specialised Tasks, Training, Equipment and Protection (STTEP) – providing operational and tactical support to the military.

STTEP was involved in the training, mentoring, and advising of the 72 mobile strike force. The Army unit later became known for using South African built REVA Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles (MRAPs) armed with heavy machine guns and implementing the relentless pursuit doctrine, which allowed it to be a vital force multiplier in the 2015 offensive against Boko Haram. According to STTEP chairman Eeben Barlow, the unit had “its own organic air support, intelligence, communications, logistics, and other relevant combat support elements”.

The agreement which was shadowed by domestic criticisms and international scrutiny, subsequently came to an end. The contractors pulled out of the country with their equipment, while the military offensive at the time continued, leveraging on the broader retooling of the military that had taken place with the injection of the Belarusian-trained Armed Forces Special Forces and delivery of new pieces of equipment including tanks, armed drones, and armoured vehicles.

Not sustaining the relationship, according to Eeben, was an error on the part of the Buhari administration. “Prior to, and following our departure from Nigeria, we issued numerous intelligence warnings to his government. These intelligence warnings were all rejected in favour of a false belief,” he alleged in 2018.

Still hiring

In June, last year, Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari launched the Integrated National Security and Waterways Protection Infrastructure, also known as the Deep Blue Project. The aim was to strengthen the security of the country’s territorial waters and the Gulf of Guinea, especially against sea piracy that was posing a serious threat to ships and sailors.

The $195 million contract for the maritime security project was managed by an Israeli firm, HLSI Security Systems and Technologies Limited. The contract which included training a special intervention force and the acquisition of air, land, and sea capabilities also involved a 10 per cent management fee and has become a subject of parliamentary inquiry.

Another instance of foreign contractors participating in military training and capacity building was in 2020. It had emerged that the Nigerian Army School of Infantry had collaborated with a company known as Starter Point Integrated Services (SPIS) Ltd to train over a thousand troops at Camp Seleya in Jaji Military cantonment.

Between 2017 and 2018, Four-Troop a company founded by veterans of Israel Defense Forces (IDF) Special Forces units, trained Special Forces personnel of the Nigerian Air Force in counter-terrorism, asymmetric warfare, and airport security. The company reportedly operates in Africa, South America, and Asia.

While the Nigerian military and government have often spoken against the use of foreign contractors, the situation on the ground appears quite different. This could be related to the limited exposure and the nature of training contracts, unlike the governors’ proposals which require field action and combat as was the case in 2015.

In February, defence chief Lucky Irabor pushed back at the call for mercenaries, insisting that the military should be trusted to do its job. “This is the essence of setting the Nigerian military up. It is our work. Rather, we are calling for more support for all stakeholders in this war against terrorists,” he said. Similarly, Babagana Monguno, the National Security Adviser, stated last year that the services of mercenaries would no longer be required as the military had the firepower and expertise to defeat insurgents.

Despite the concerns and public reluctance from the authorities, however, involving mercenaries in local counter-insurgency operations can be advantageous.

“Firstly, PMCs are generally cheaper than maintaining a standing army,” Dr Sean McFate, a Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council and a national security strategy expert, told VICE in 2016 in reaction to developments in Nigeria.

“Second, you don’t have to deal with corrupt, politically ambitious officers. The third is that if you are a rich, small country that wants to participate in war but doesn’t have the citizens who want to serve in the military, PMCs are a good option… There are a lot of “advantages,” quote unquote. A lot of them are dubious or raise concerns, but they certainly offer short-term advantages.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter