Nigeria’s Deadly History Of Electoral Violence In Five Charts

Ever since it gained independence, Nigeria’s electoral processes have been rattled by all forms of violence. The patterns remain strong as the country prepares to hold another round of elections next year.

Nearly all of Nigeria’s general elections since independence have been tainted with the brush strokes of violence.

The outrage that trailed the first election conducted in 1964/5, for example, claimed more than 200 lives, especially in the Southwest, according to Human Rights Watch (HRW). The country also experienced “massive post-election violence” following the 1983 election, with several lives lost and property destroyed.

Even the 1993 presidential election, widely adjudged to be the freest in the country’s history and with no serious episodes of violence, did not have a clean record. Its annulment by the Ibrahim Babangida-led military administration triggered public outcry and a wave of protests. Campaign for Democracy (CD), headed then by Beko Ransom-Kuti, estimated that over 100 peaceful demonstrators and passers-by were gunned down by security agents, who were supposedly trying to contain the violent offshoot of the July protests.

Little has changed since Nigeria’s return to democratic rule in 1999 too.

There was widespread violence following allegations of fraud regarding the 1999 election that ushered in the presidency of Olusegun Obasanjo. It is estimated that about 80 people died. Similarly, at least 100 people were killed during incidents of violence triggered by federal and state elections in 2003, and over 300 people lost their lives in connection to electoral violence four years later, with pre-election violence alone claiming more than 70 lives.

Again, in 2011, post-election violence led to the death of at least 800 people over three days of rioting in 12 states across northern Nigeria — the worst case so far in the country’s political history.

“The violence began with widespread protests by supporters of the main opposition candidate, Muhammadu Buhari, a northern Muslim from the Congress for Progressive Change, following the re-election of incumbent Goodluck Jonathan, a Christian from the Niger Delta in the south, who was the candidate for the ruling People's Democratic Party,” noted Human Rights Watch.

During and after the general elections in 2015, more than 100 people lost their lives, according to the International Crisis Group. And finally, the European Union Election Observation Mission said about 150 people were killed due to violence linked to the last national elections of 2019.

In trying to understand why what is supposed to be the hallmark of democracy faces such repeated challenges, fingers have been pointed at various factors. These range from weak governance to the ineffectiveness of security forces, poverty and unemployment, abuse of power, political alienation, a climate of impunity, a ‘winner-takes-all’ political system, and the proliferation of small arms.

Thanks to the documentation efforts of the Nigeria Security Tracker (NST), we are able to study the trend of political and electoral violence in the country more closely from 2014 to date. NST creator and research associate with the Council on Foreign Relations, Asch Harwood, explained that the tracker expanded its scope to include election-related violence just before the 2015 national elections.

The statistics corroborate figures from the International Crisis Group and the European Union Election Observation Mission about the national elections of 2015 and 2019.

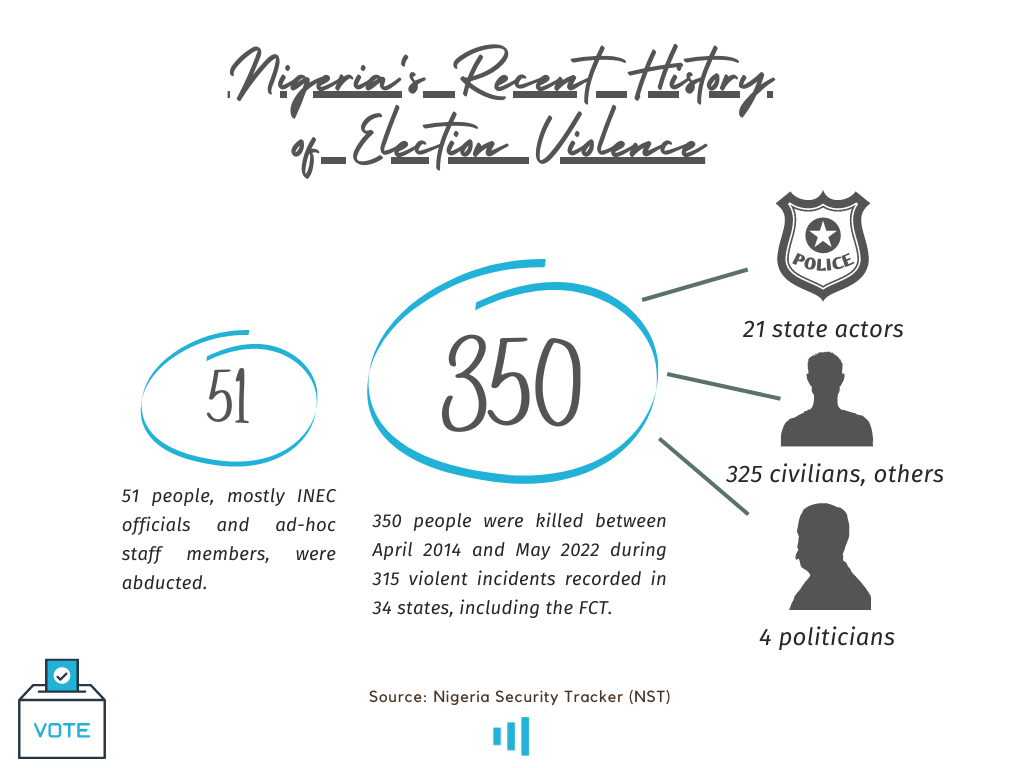

Between April 2014 and May 2022, according to press reports catalogued by the tracker, at least 350 people lost their lives to electoral violence in Nigeria. Fifty-one (51) others, mostly officials of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), were abducted in the same period.

The violence comes in various forms, such as arson, assassinations, ballot box snatching, coercion, forceful disruption, kidnapping, hate speech-induced crises, shooting, thuggery, and so on.

Most of the victims were civilians but 21 security personnel also lost their lives.

Naturally, the highest number of deaths were recorded in 2015 and 2019 when general elections were conducted.

But one interesting quality of the NST dataset is that it also collects information outside of the general elections. The way Nigeria’s politics has evolved, governorship elections and other electoral activities take place in the middle of the four-year general elections cycle. So the tracker captures violent activities within those periods as well.

There have so far been 25 deaths attributed to electoral violence this year, making it almost as bad as what was recorded for 2014.

The year with the least number of incidents and fatalities was 2017 while 2019, which ushered in Muhammadu Buhari as president for the second time, is the year with the highest number of deaths and abductions.

Another form of analysis that is possible with the NST data is comparing figures between the various states.

Between 2014 and 2022, the states with the highest number of incidents were Rivers, Lagos, Kogi, Ondo, and Ekiti, respectively.

Rivers and Lagos states again topped the list of places with the highest number of deaths followed by Taraba, Bayelsa, Delta, Ebonyi, Kano, and Kogi. When it comes to abductions, the greatest number of victims was recorded in Katsina, then Imo, Enugu, Kogi, and Sokoto.

Another dimension electoral violence has taken in recent times is increased attacks on INEC facilities across the country.

The commission stated last year that between 2019 and May 24, 2021, its offices were attacked 41 times across 14 states. These included 20 cases of vandalisation, 18 cases of arson, and three cases involving both.

INEC blamed 18 of the incidents on anti-police brutality (End SARS) demonstrators, 11 on “unknown gunmen” and hoodlums, six on thuggery during elections, and the rest on bandits, Boko Haram insurgents, and post-election violence.

The incidents were mostly concentrated in the Southeast and Southwest regions of the country. Seven of the cases took place in Imo, six in Osun, five in Akwa-Ibom, and four in Abia and Cross River. The rest were recorded in Anambra, Bayelsa, Borno, Ebonyi, Enugu, Kaduna, Lagos, Ondo, and Taraba.

Concerned by the relentless pattern of violence accompanying Nigeria’s general elections, Human Rights Watch had in 2019 urged President Buhari to see his return to the top position as an opportunity to address the issue.

“Nigerian voters have entrusted Buhari with another opportunity to address the nation’s serious human rights problems, including political violence,” observed HRW Nigeria researcher Anietie Ewang. “He should start by reforming the security forces to ensure strict compliance with human rights standards, and prompt investigation and prosecution of those credibly implicated in abuses.”

This report was produced in partnership with HumAngle Services.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter