Niger Coup Leader’s Terrorism Claims Stoke Anti-West Sentiment in Northern Nigeria

Niger Republic’s coup leader, General Tchiani, has accused Nigeria of harbouring terrorists on France’s behalf, deepening mistrust in the West and reshaping geopolitical alliances in northern Nigeria.

When General Abdourahamane Tchiani, Niger’s coup leader, sat before the camera on Dec. 25, 2024, his words did not dissolve into a routine presidential holiday message. Instead, they spread like wildfire from Niamey, the capital of Niger Republic, to Kano in northwestern Nigeria, igniting heated discussions in the tea joints of northern Nigeria.

Tchiani, in a viral video of the speech, accused the Nigerian military of colluding with France to harbour terrorists, claiming the objective was to destabilise Niger.

His choice of language was deliberate. Although French is Niger’s official language, he spoke in Hausa—a lingua franca in both Niger and most parts of northern Nigeria, spoken by millions across West Africa. The message was clear: “Nigerian leaders are French puppets.” The implications, however, were vast.

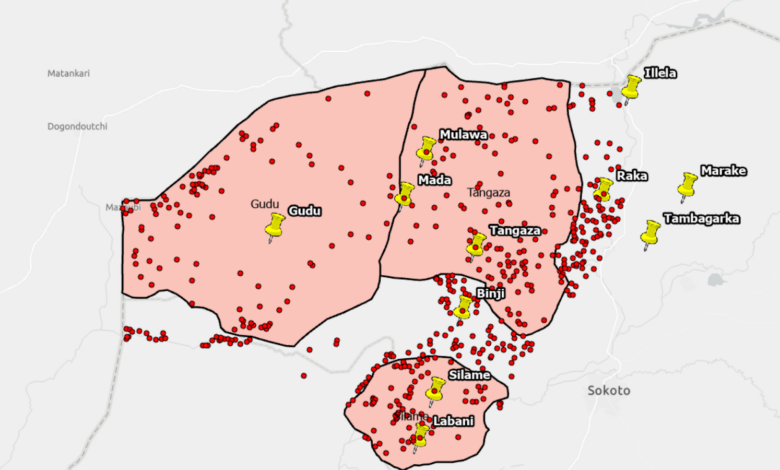

“The intelligence report we gathered from the terrorists we arrested revealed to us that France has created terrorists called Lakurawa in a forest called Gaba in Sokoto State,” Tchiani claimed. “An agreement was made between France and ISWAP on March 4, 2024. That agreement detailed how Gaba forest would be made a base for Lakurawa, from which terrorists would be deployed to Sokoto, Zamfara, and Kebbi.

“[One of the terrorists] told us that the Nigerian government is aware of the plan, but we didn’t take him seriously because we thought he was trying to mislead us.”

“So we called the intelligence officer and informed him about France’s plans. He promised to investigate and sent a team. We accommodated them, took them to prisons, and they spoke with the terrorists, who confirmed France’s involvement. It was only later that we realised the person we confided in, Ahmed Rufai, is the contact and logistics coordinator between France and the terrorists,” he claimed.

“Nigeria’s National Security Adviser, Nuhu Ribadu, is aware of this and took no action. Later, we realised they were accomplices. The Lakurawa were recruited to destroy our oil pipelines leading to Benin because France had been asking for the locations of our pipelines. Another goal is to prevent our people from engaging in farming.”

These claims polarised public opinion in Nigeria. Some saw them as validation of long-standing suspicion about foreign influence, while others dismissed them as manipulative rhetoric amid diplomatic tensions following Niger’s coup against President Mohamed Bazoum.

It is worth noting that in November 2024, Nigeria’s Defence Headquarters classified Lakurawa as a deadly terrorist group in northwestern Nigeria with jihadist affiliations. HumAngle’s investigations revealed that the group had operated in the region for around six years. However, local security authorities had previously dismissed it as a harmless faction of herders from Niger.

A message that resonates

For many in northern Nigeria, Tchiani’s accusations did not seem outlandish. The Nigeria-Niger border is an artificial colonial divide, cutting through communities that share language, culture, and history. Thus, when Nuhu Ribadu dismissed these claims, scepticism persisted.

“The leaders of Niger should be aware that we have no problem with them. The terrorists are our common enemies, and we should confront them together,” Ribadu countered.

“They should please check again. There is no way Nigeria would support terrorists to attack Niger.”

On the claim that France has military personnel stationed in Nigeria preparing to attack Niger, Ribadu was equally firm:

“Nigeria has never given its land to any foreign troops—not even Britain. When the [United States] requested a military base, we denied them, but Niger gave them permission,” he said.

But for Shuaibu Lawan*, a trader at the Magama border, Nigerian politicians cannot be trusted. According to him, anything is possible.

“We’ve heard the stories of how planes are dropping weapons to the terrorists in Zamfara because the target is to destabilise Northern Nigeria so that mineral resources such as the gold in Zamfara can be stolen,” he said.

Although fact-checked as false, the claim that helicopters drop arms for terrorists in northwestern Nigeria remains popular. The same video has resurfaced multiple times, alternately claiming the terrorists were in Zamfara or that they were Boko Haram fighters in the northeast.

A growing distrust

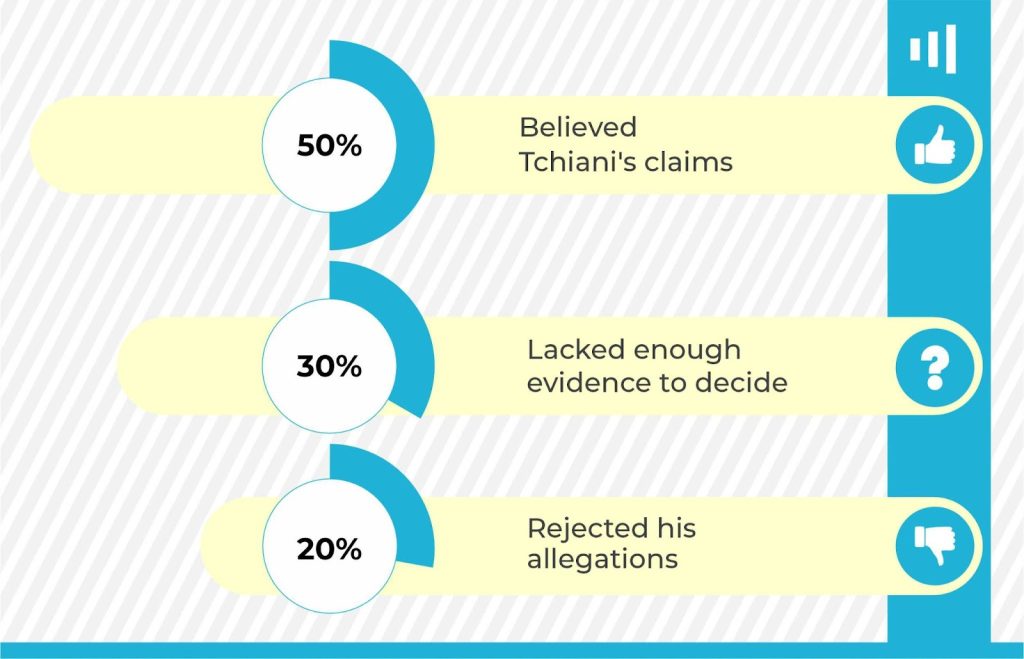

A survey conducted in Kano for this report found that 50 per cent of the respondents believed Tchiani’s claims, 30 per cent were undecided, and only 20 per cent rejected them outright. Many pointed to President Tinubu’s perceived closeness to France as a reason for suspicion.

While many say that such serious allegations would not have been made by Niger authorities if they were not true, others expressed their mistrust with the Nigerian leaders as a main reason why it could be true.

One respondent, Abubakar Saidu, explained his reasoning:

“President Tinubu has been close to France since he assumed power, and we all know that France can create terrorists to attack Niger due to their diplomatic fallout.”

So when Tinubu signed an agreement with France to increase food security and mineral resources, that action was looked at with suspicion and misinterpreted to be a deal to station the French military in Nigeria. This led to groups in Northern Nigeria expressing their resistance to the French presence in the country.

This sentiment gained more traction after US Congressman Scott Perry accused USAID of funding Boko Haram, reinforcing long-standing suspicions about Western interference in Nigeria.

Tchiani’s statement fits seamlessly into this narrative. His accusations did more than suggest France was supporting terrorists—they reinforced a belief that many in the region already held: that the West is pursuing self-serving interests and that alternative alliances must be explored.

As his words, spoken in Hausa, spread across borders, distrust in Western powers deepened, fuelling the region’s growing pivot towards Russia.

From scepticism to geopolitical realignment

Allegations of Western support for terrorists in northern Nigeria are not new. Tchiani’s claims merely added legitimacy to a narrative that has already taken root. Clerics and social media influencers have all come out accusing the West, particularly France, of destabilising Africa and engaging in neo-colonial pursuits.

In recent years, northern Nigeria has witnessed a surge in pro-Russian sentiments. During the #EndBadGovernance protests, some demonstrators in the region waved Russian flags—not just as a rejection of Western influence but as a call for military intervention.

“We need Putin here,” one protester in Kano said. “He should come and save us from the hardships caused by Tinubu. We need a military takeover.”

This shift mirrors trends in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, where Russian-backed juntas have replaced Western-aligned governments. Some Nigerians now see Russia as a potential liberator, even willing to back a similar coup in their country.

Balarabe Ismail, a security analyst in Kano, explains: “This is why young men are carrying placards, demanding better governance, and chanting slogans in favour of Russia. They believe a military takeover will ease their struggles and see Russia as the only power willing to support that.”

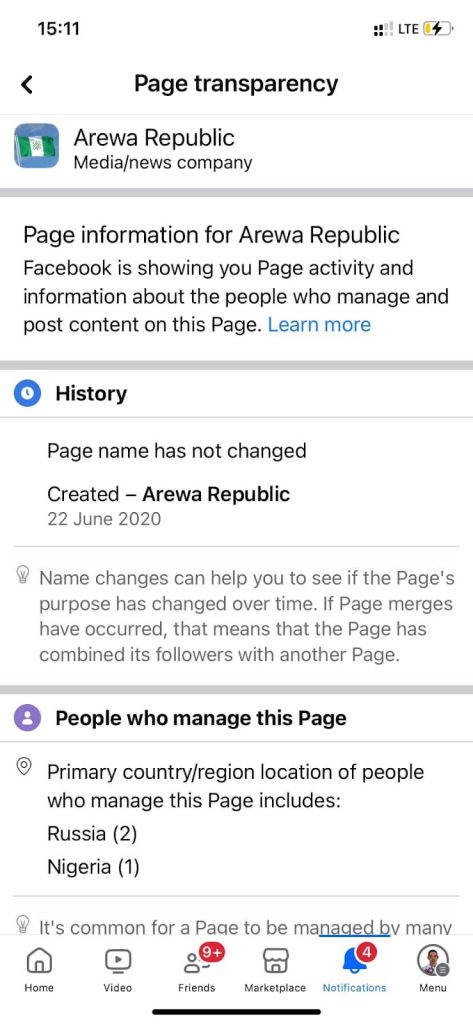

This shift has been exploited by social media accounts traced to Russia, which amplify ethnic divisions and anti-West rhetoric. The Facebook page “Arewa Republic” – operated partly from Russia – regularly calls for the balkanisation of Nigeria.

The challenge of fact-checking

Yet, a fundamental problem exists: Tchiani’s claims lack verifiable evidence. A 2021 study traced the emergence of the Lakurawa terrorists in Sokoto to 2017—years before Tchiani’s alleged France-ISWAP agreement. The study revealed that local leaders initially recruited Lakurawa fighters from Mali to combat terrorism in their neighborhoods.

“The District Heads of Balle and Gongono met with Alhaji Bello Wamakko, then Chairman of MACBAN, to discuss how to tackle Zamfarawa (terrorists). They ultimately decided to hire Lakurawa from Mali,” the study quotes a local leader as saying.

This account, published three years before Tchiani’s allegations, suggests the militia’s origins had little to do with France or any agreement made with ISWAP in 2024.

Still, in a region where trust in official institutions is fragile, debunking misinformation is no simple task. A government-issued denial, whether in English or Hausa, does little to change minds. A Western-backed fact-check only deepens suspicion.

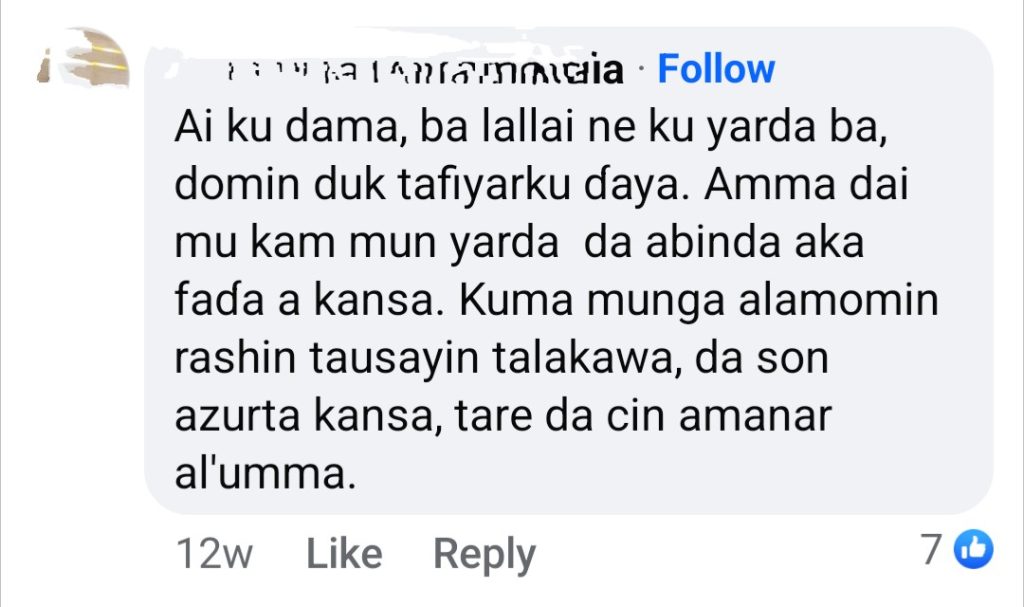

For instance, when BBC Hausa published testimonies refuting Tchiani’s claims, the reaction was overwhelmingly negative.

“We know you won’t agree because you’re all on the same side,” one commenter wrote. “But we believe what [Tchiani] said. We have seen the signs—our leaders lack compassion, they only serve themselves, and they betray their people.”

An information warfare?

Security analyst Balarabe Ismail explained that countering misinformation and foreign propaganda in northern Nigeria requires more than fact-checking; it demands engagement on the people’s terms – through trusted community voices.

“This is the new reality of information warfare. It is no longer just about truth versus falsehood. It is about who controls the language in which truth is told. It is about who defines the enemy—and, ultimately, who is believed,” Ismail said.

Tchiani’s speech was not just a presidential address; it was a strategic move in a broader battle for influence. Unless effectively countered, such narratives will deepen distrust, reshape alliances, and push northern Nigeria further toward alternative geopolitical players.

“The war for hearts and minds is underway,” Ismail concluded.

General Abdourahamane Tchiani of Niger accused Nigeria of collaborating with France to destabilize Niger by harboring terrorists, specifically in a viral speech delivered in Hausa, resonating deeply in northern Nigeria where suspicion of foreign influence is prevalent.

Claims included French support for a terrorist group, Lakurawa, with Nigeria's tacit permission. Despite Nigeria's National Security Adviser Nuhu Ribadu's dismissal of these accusations, public opinion remained divided, with many not trusting Nigerian political motives.

The allegations of Western influence and military plots were further amplified by reports of a potential US-French military presence and previous accusations of the West funding terrorist groups like Boko Haram. This has fueled distrust in Western powers, leading to a rise in pro-Russian sentiment and calls for military intervention, as seen in other African countries shifting alliances away from Western influence. The spread of these narratives, bolstered by social media and reinforced by geopolitical fears, underscores the importance of addressing misinformation and engaging with local communities to rebuild trust and counteract destabilizing narratives.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter