Neglected Elderly Women Sleep On The Streets After IDP Camp’s Closure In Borno

When the state government’s authorities arrived at the Kawar Maila makeshift camp about a year ago to distribute relocation notices to every household in Kawar Maila, the elderly women residents were absent. Where did they go?

One morning about a year ago, when government officials arrived at the Kawar Maila makeshift camp to distribute relocation notices, the elderly women were absent. They had ventured out into the streets and markets of Maiduguri, North East Nigeria, in search of sustenance.

By the time they returned to the displacement camp, the gates had been sealed shut, denying them access while the relocation notice distribution was underway. Security personnel stationed at the entrance resisted their efforts to make their way in and join the exercise.

The camp was officially closed on Feb. 25, about a year after the relocation notice was given. The authorities allocated shelter to those with relocation cards in a housing estate along Bama Road. Lacking the necessary documentation, the elderly IDPs were excluded from this provision. As a result, they now find themselves homeless, dispersed throughout the host community, struggling with the challenges of survival in their advanced years.

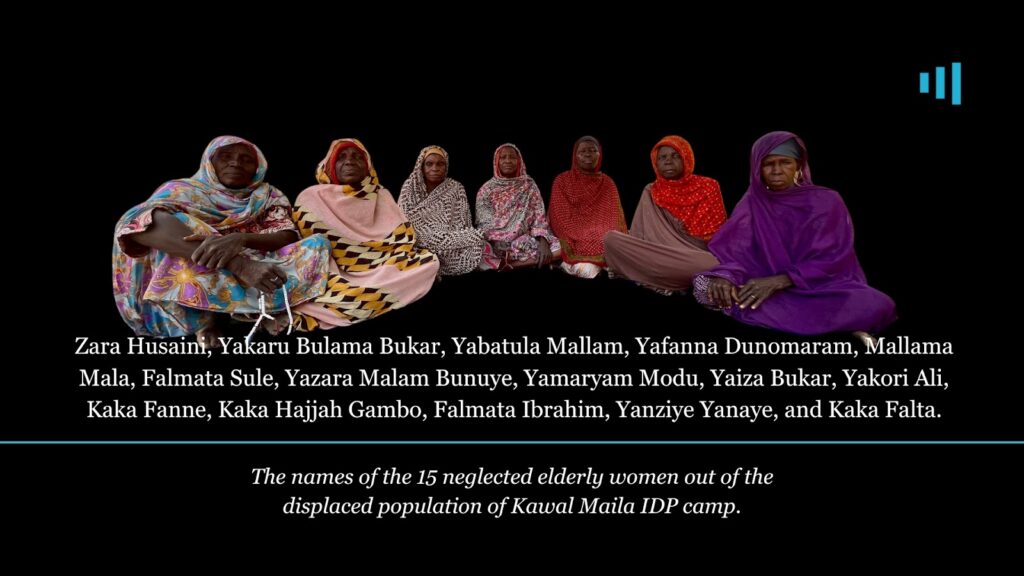

HumAngle found that this omission affected at least 15 elderly women, including divorcees, widows, and single mothers aged between 60 and 90 years.

Life for old people at displacement camps in the region is often characterised by the absence of humanitarian assistance, hunger, discrimination, inequality, and hardship. This is especially because many of them have to fend for themselves as they do not have caregivers, and the camps have no provisions for special service providers.

Seventy-year-old Zara Hussaini, one of the affected women, has been displaced for the past ten years since Kawuri, her village in the Konduga area of Borno, was attacked by Boko Haram. She had lost her husband before this and decided not to remarry. She took care of herself and her daughter by selling produce from small-scale farming.

After Boko Haram’s attack, Zara and others fled to Maiduguri and settled at the Kawar Maila camp. For many elderly residents like her, the journey to the camp marked the beginning of a new and unexpected chapter in their lives.

The difficult living conditions at the informal camp pushed her to beg frequently. “I don’t have anything to eat and no one to help me in the camp. I am an old woman with no one around to take care of me,” Zara told HumAngle.

She ventured far from the camp because she no longer received alms in the area. She also felt embarrassed and tried to avoid familiar faces who could mock her. She roamed the streets, and she mostly begged in the market areas, especially the Maiduguri Monday Market and Gamboru Market.

“Sometimes when my neighbours get humanitarian assistance like foodstuff from the government or non-governmental organisations, they give me small. Every morning, whether I am sick or healthy, I must go out to beg, or else I would starve to death,” she said, close to tears.

The morning the relocation cards were distributed, she went out, as usual, to seek alms close to the Monday Market. When she learnt what was going on and got to the camp, it was too late. According to Zara, she tried calling the attention of the security guards and those conducting the evacuation process, but she was neglected. One of the officials asked why she would leave the camp in the morning if she truly lived there.

“I tried all my best to inform them that I was a resident of the camp, but they did nothing. I was humiliated and threatened to leave or be whipped.”

Another victim, 75-year-old Maryam Abatcha, fled a violent terror attack on their village in the Dikwa Local Government Area 11 years ago.

When she first moved to the camp, she worked as a farm labourer. However, because of her age, she could not cope with the tedious work and had to stop.

“I fell sick often, and I don’t have the energy to plough anymore. I started scouting for what to eat around the Gomboru marketplace,” she explained.

She started taking menial jobs at the market, sieving dirt from grains and cereals. The work was tedious, but it was the only thing she could afford to do. She also picked discarded foodstuff from the ground, which she used to prepare meals at home.

“I eat once a day,” she said.

She had the same experience as Zara when she heard about the government officials’ visit to the camp. The registration process was almost over, and despite her protest, they would not let her in.

The excluded elderly residents gathered under a tree and lamented their predicament.

“We were all left feeling lost and powerless,” recalled Karu Bulam Bukar, 80, her voice tinged with frustration and sadness. “I felt a deep sense of sorrow and injustice.”

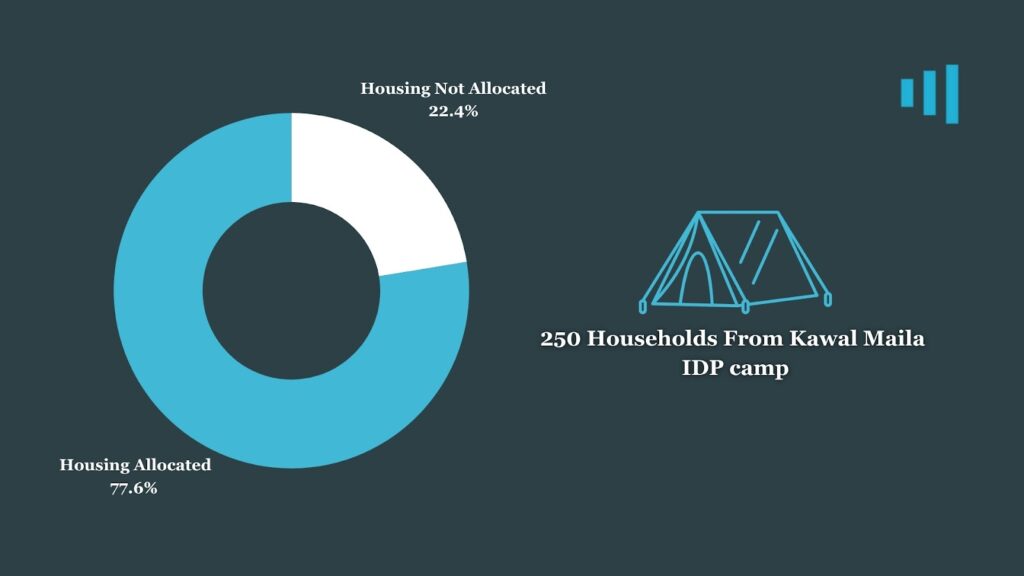

Eight months later, the long-awaited moment arrived when government officials visited again to close the camp. They systematically conveyed each household carrying relocation notices to new accommodations at the estate having 1,000 housing units in Dalori, a village along Bama Road.

As families eagerly awaited their turn to receive their new housing assignments, the 15 elderly women watched from the sidelines, their hopes diminishing with each passing moment. Out of the 250 registered households at the camp, only 194 got housing allocation.

Mallam Modu Bintube, chairman of the displaced community from the Kawar Maila camp, urged the government to provide housing for affected elderly women.

“I thank God and the governor for providing us with these wonderful houses,” he said.

“We are pleading with the government to do something about the 15 old women who are homeless now. The old women living without children or grandchildren did not get the house because they went out begging and some to work when the relocation notices were shared with households at the camp.”

He noted that many of the women have been sleeping at the market and in other odd places since the camp was shut down in February. Some others squat with family and friends.

Since she doesn’t have anyone to help her, Zara spends her nights in the market area in front of shops and sometimes under a tree.

“I don’t know where to go since I was not given a house while others got them. I sleep in the market area. When you beg someone to allow you to sleep in their house, they won’t agree for so many reasons,” she said.

Yakori Ali Moram, 82, has also been sleeping under tables in Gomboru Market, using her wrapper as a blanket.

“I only take my bath in the public toilet during the day and I do this a few times a week. Having no home means I must survive anything that comes my way in the night where I sleep. I sleep under dirt, cold, and all uncomfortable situations,” she said.

Kaka Falta, 70, is among the few lucky ones who got temporary shelter from their relatives.

“I am grateful to them, but you know, living in someone’s house comes with its peculiar challenges. For now, I must bear all the consequences until I find a place,” she said.

The 15 women share a common wish. They want a place they can call home once again. Each night, as they huddle together under the open sky, their thoughts drift back to the days when they had roofs over their heads and walls to shelter them from the elements of uncertainty.

“We long for a community where the elderly are valued and respected, where our voices are heard and their needs are met,” Kaka said.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter