More Heat, New Inequities: The Poor At Greater Risk When Temperatures Climb

The poor in northern Nigeria disproportionately feel the impact when temperatures rise at the end of the harmattan period. With human-made climate change increasing temperatures, heatwaves will become more deadly.

This time of year the weather in the northern part of Nigeria changes from the cool-dry harmattan to the hot season that will last from March to May.

As tens of thousands of displaced people across the country will tell you, this makes living in makeshift camps, in huts built of heavy plastic, unbearable.

As the temperature rises, vulnerable groups will struggle. Every year people die due to the body overheating during hot seasons, and as the effects of human-caused climate change become clear, it will only get worse.

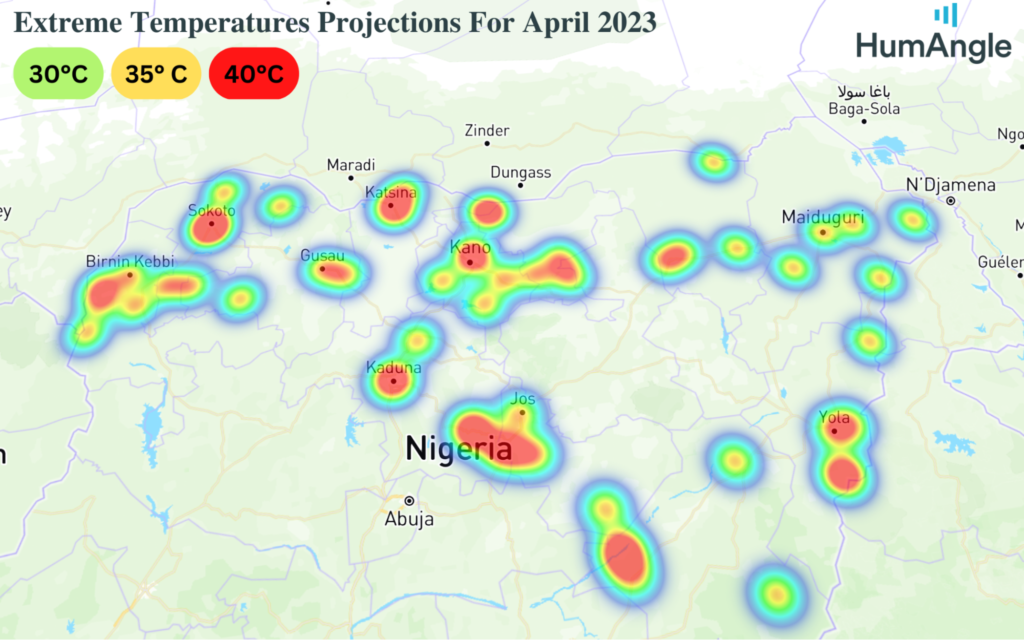

Weather projections released by the Nigerian Meteorological Agency (NiMET) in January show that the intensity of heat this season will reach a peak of over 40°C in some days of March through May, especially in Mafa and Aba Khalli communities in Borno, northeastern Nigeria, including Maiduguri, the state’s capital.

The meteorological agency also disclosed that Kebbi, Kano, Sokoto, and Katsina states in the northwest will experience severe hot temperatures and heat waves.

What are heat waves?

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) defines heat waves as a period of prolonged, excessively hot weather that is often accompanied by high humidity.

In Nigeria’s tropical climate, there is a notable difference between temperatures in the daytime and the nighttime. Christopher Sako, a climatologist, tells HumAngle that “sometimes this difference is as much as 4°C to 6°C, but when there are heat waves, the difference closes in.”

Worldwide, thousands of people die every year from the effects of heat. In 2022, a joint analysis carried out by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA) and the International Federation for the Red Cross (IFRC) revealed that heat waves are becoming deadlier.

The analysis stated that heatwave tracking has been relatively poor, yet the effect could be devastating in West and Central Africa. “The number of hot days experienced each year in low-income countries could triple within two decades compared to the 1961–1990 average,” the report says.

Heatwaves are becoming more frequent and severe because of climate change. Sako explains that in a tropical climate, the average temperature starts from 18°C, but it has gradually increased to 24°C. “Before, we would experience two incidents of heat waves in a decade, but it has intensified to four to five times” he says.

The UN OCHA and the IFRC also revealed that 38 heat waves were recorded between 2010 and 2019 which accounted for 70,000 casualties globally. But the report says there are gaps in data which means that figures are “grossly underestimated.”

Thermal inequity

The disproportionate impact of heat is associated with the disparity in the effects of climate change in urban areas. The phenomenon is known as “thermal inequity”, a situation when people living in low-income areas suffer the most.

According to the climatologist, the severity of heat waves can be prevented and managed in a way that does not threaten one’s well-being. He says cooling systems and staying in well-ventilated rooms are some of such ways to counter its dangers.

However, most vulnerable groups such as internally displaced persons (IDPs) and those in low-income communities do not have access to such expensive systems or live in settlements and shelters with adequate provision for airflow.

Thousands of displaced persons in the northeastern state of Adamawa will have to endure high temperatures forecasted to reach 40°C on peak days this year. They live in tarpaulin tents in overcrowded displaced people’s camps. The makeshift shelters are poorly ventilated and retain unbearable levels of heat.

“When it becomes hot, you do not dare to enter this tent and sleep because of how scalding it is,” says Dahiru Isa, a displaced man in Malkohi Camp, Adamawa. He tells HumAngle, sometimes he and his family have to sleep outside their shelter due to the heat.

Tarpaulin tents are made of heavy-duty polyethene material that is usually waterproof but “they are not protective enough,” Dr Habiba Ibrahim, a Resident Doctor with the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital, says.

“The congestion and then the heat makes it even worse because then you realise that everyone is sweating and there is a mix of bodily fluids with not enough air. The heat itself is damaging to the skin and to mental health.”

Tougher for the poor in urban areas

Urban areas and cities are usually densely populated not just because there are more people inhabiting them but also because there are houses, shops, and in some cases, industrial buildings constructed in a close shelter.

Activities in cities, such as the movement of vehicles and construction of highrise buildings and urban landscapes like roads, parking lots and sidewalks, are what make urban areas hotter than rural areas. Experts refer to them as ‘Urban Heat Islands’ (UHIs).

Heat can also be created by energy from people and their activities. According to a National Geographic resource report, “whether they [people] are jogging, driving, or just living their day-to-day lives. The energy people burn off usually escapes in the form of heat. And if there are a lot of people in one area, that’s a lot of heat.”

Sako, the climatologist, states that thermal inequities come into play when those who can afford cooling systems try to mitigate risks of heat for themselves and generate more heat for those who can’t afford them. He explains that in a neighbourhood where the rich can put on air conditioning but the poor can’t, it means the poor are positioned to feel more heat as well as be adversely impacted.

Urban planners, especially in Nigeria, tend to take the general concept of global warming for granted, he notes.

“The only way we know how to urbanise is to exchange flora and fauna for concrete and steel. If you remove all the greenery in a place and replace it with coal tar, iron, concrete, metal roofs or aluminium roofs, at the end of the day what happens? The micro-climate of that place which used to be cool has been replaced by things that absorb and emit heat.”

Sako explains that heat waves have only gained awareness globally because there are lesser natural covers that can absorb them and it is because they have been taken away.

The disproportionate impact of heat waves has also been made worse in northern Nigeria due to the country’s unreliable electricity supply, and alternative power-supply means such as generators and inverters are unaffordable for many people.

Heat-related illnesses intensify

With the onset of the hot season comes the increased spread of infectious diseases such as Lassa fever, Yellow fever, Measles, Monkeypox, and Cholera.

While displaced people are affected in ways that come with their living conditions, those in low-income communities also face worsening health due to factors like poor hygiene and the lack of a good food preservation system.

Dr Habiba explains that there are bacterial organisms that thrive in the heat, as well as food items, rot faster during the hot season. This exacerbates diarrheal infections amongst people living in low-income communities.

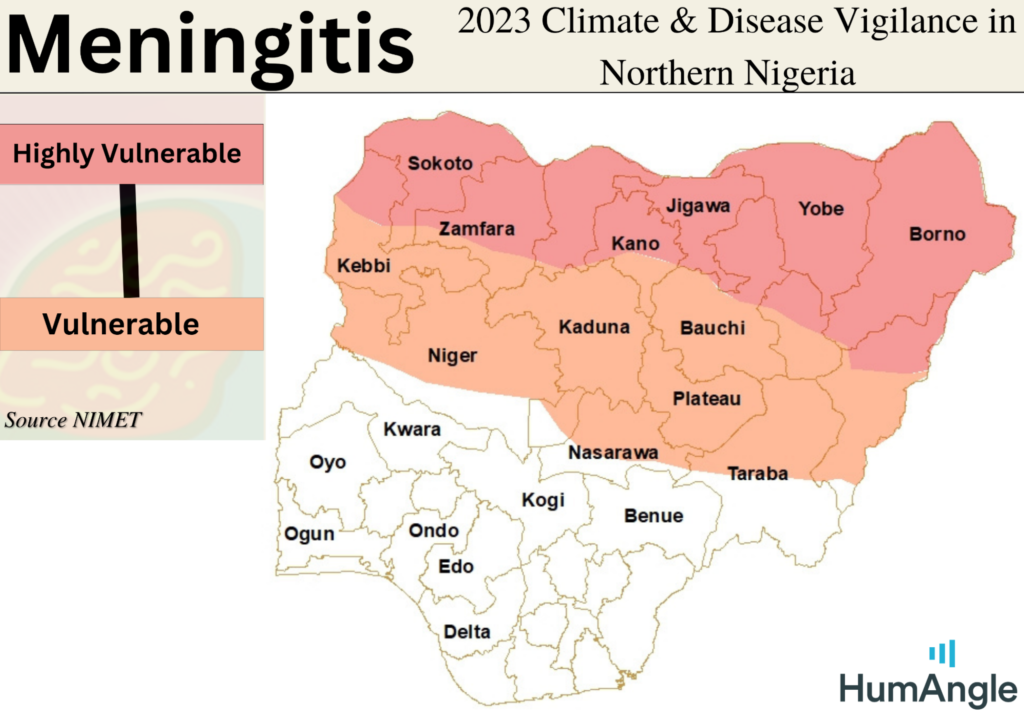

NiMET’s seasonal climate predictions also show the disease trend of the year due to weather. The environmental conditions for the prevalence of Meningitis (an inflammatory disease that affects the brain) peaks around April and May in the Sahel regions of Nigeria.

According to the meteorological agency, many are susceptible to Meningitis when the humidity in the air is less than 20 per cent, and the temperature falls between 25°C and 32°C or higher. This means those living in densely overpopulated neighbourhoods could be at greater risks especially on dusty days in April and May.

In 2022, NiMet revealed that several states in the north were hotspots for Meningitis cases at some points in the year. In a Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) report, there were at least 961 confirmed cases which were prevalent in the northern region of the country.

Dr Habiba notes that adverse weather conditions prey more on the health of the poor as preventive measures and medications can be unaffordable.

She says even when people seek medical help, “the cost is very challenging. Diagnosis comes with a lot of tests, a lot of supportive therapy and some may need to be in Intensive Care Units (ICUs) but then where is the money to do it.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter