More Attacks, More Displacements: Inside DR Congo’s Ituri Violence

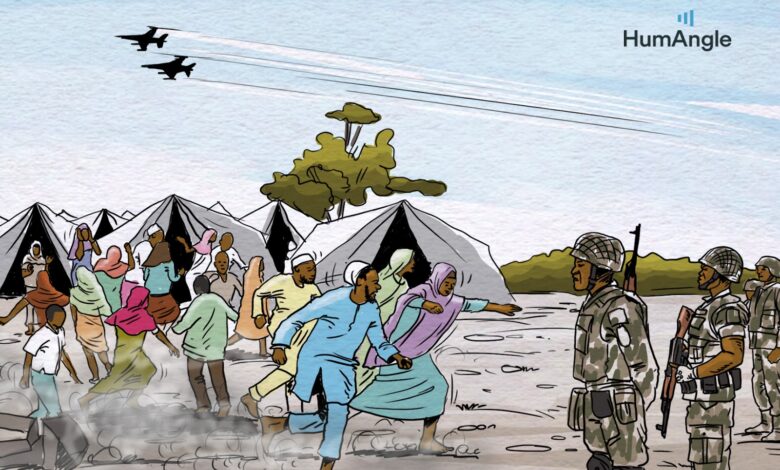

A spate of attacks in Ituri, DR Congo, is creating an atmosphere of fear among the displaced persons who are increasingly afraid of what lies ahead.

The camp was supposed to be a refuge for some 20,000 Congolese who had been uprooted from their homes since 2017. But the Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) were helpless when a rebel group stormed the camp in an overnight attack on Plaine Savo in Ituri Province of DR Congo on Tuesday, Feb. 1, with machetes and guns, cutting throats and lighting houses on fire.

The United Nations peacekeepers and the Congolese army base was only about one mile away. But help did not come immediately.

“I first heard cries when I was still in bed. Then several minutes of gunshots. I fled and I saw torches and people crying for help and I realised it was the CODECO militiamen who had invaded our site,” Lokana Bale Lussa, a camp resident, told Reuters.

Bullets were reserved for those who tried to run. Those who could not escape were killed or attacked with machetes and knives in their sleep.

The rebels killed at least 62 people including women and children of the Hema ethnic group, with 36 injured in the brazen attack. The headmaster of a school supported by the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) in the area reported that two of his students were among the dead.

Thinking there would be better protection, many of the 24,000 displaced persons had initially fled to the camp from violence in Djugu territory which borders Lake Albert and Uganda to the east, in 2019, according to the NRC. The Djugu area is the epicentre of the feud between the Lendu and Hema communities.

The UN Mission in the country (MONUSCO) confirmed the attack was carried out by members of the Cooperative for the Development of the Congo (CODECO) – a loose association of Lendu rebel groups which has since split into rival factions. CODECO fighters are drawn mainly from the Lendu farming community, which has long conflicted with Hema herders. Notedly, Lendu leaders have distanced themselves from the rebels.

Wave of attacks

What happened in Plaine Savo is increasingly common in Ituri province in the eastern region of DRC where more than 100 armed groups including CODECO, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) rebels and the Ugandan Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), operate.

Like Savo, many towns in North Kivu (where FDLR rebels are domiciled) and Ituri provinces have seen an influx of more people being displaced by the violence intermittently. Some of these communities hosting displaced people have seen repeated attacks.

The security situation in the East has deteriorated even after President Felix Tshisekedi announced a “state of siege” in North Kivu and Ituri in May 2021. The martial law put the military and the police in charge of the regions to end the bloodshed. But the terror has continued unabated.

For instance, between June 17 -18, 2021, in Djugu Territory, two children, two men, and a woman were brutally murdered—beheaded with machetes, and over 150 houses were set on fire when the militia attacked two different villages hosting displaced people.

The CODECO rebels attacked four other IDP sites between Nov. 19 and 28, 2021, including the village of Drodro, killing at least 58 people from the Hema community- nine women and four children. In Tché, almost 1,000 shelters were wrecked.

The UN Mission said it documented 10 attacks on IDP sites in 2021 in Ituri, North Kivu, and South Kivu – at least 106 people were killed, 16 injured and at least seven women were raped.

Repeated displacement

The string of attacks on displaced people has raised concerns about an escalating humanitarian crisis, causing repeated displacements in DRC. The attacks add up to an already complex displacement situation in the East and pose huge risks for the people who fled their homes, the UN refugee agency warns.

Nearly 5.6 million Congolese have been displaced from their homes, according to a count in Nov. 2021 by the United Nations refugee agency. The majority lives among host communities, but more than 330,000 are sheltered in displacement sites.

In Ituri alone, more than 1.9 million people and almost a million children have been forced from their homes by conflict.

For many, the danger of staying behind has become too great just as it is, moving into another camp or religious places through rutted roads. But they risk it anyway, travelling long distances on foot.

After the Plaine Savo massacre, nearly 30,000 people, including those who were displaced from the camp and the surrounding sites of Lala and Tshukpa, travelled more than three kilometres to the centre of Bule located on the hilly part of Djugu while others would have found refuge in the bush. The site’s size has been doubled, forcing the newly arrived families to sleep in the open.

Worsening humanitarian Crisis

New displacements put more pressure on the areas hosting internally displaced people, accentuating the demand for humanitarian aid more than ever before in Ituri, the province with the largest number of people in need – 2.9 million people.

The UN children agency says most displaced families are absorbed into local communities that are barely able to provide sustenance for themselves, let alone support those arriving from other areas. “Those living in informal settlements face even harsher conditions, with families of six or more people often sharing cramped tarpaulin and palm leaf shelters that serve as spaces for eating, sleeping and living,” UNICEF says in a report.

The main needs in host communities include food, shelter, and health care, as well as psychosocial assistance and healthcare services.

According to the UN refugee agency, food insecurity affects nearly 3 million people, particularly in the territory of Djugu, where 20 per cent of the population is in rural areas in the emergency phase (IPC4).

Severe acute malnutrition affects nearly 5,000 children under the age of five, while nearly 48,000 pregnant women are at risk of giving birth while on the move, exposing themselves to complications that would aggravate maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality, which are already too high in this province, the agency said.

This comes even as about 39 health structures were destroyed in the province in 2021. Humanitarian officials say the lax security and restricted access by road in the region are hampering the delivery of humanitarian assistance, deepening the humanitarian crisis and creating an atmosphere of fear among the displaced, who are increasingly nervous about what their future might hold.

How did the current crisis unfold?

For many, the cause of the ongoing conflict in Ituri province is indefinite, but some believe the violence has its roots in the ethnic dynamics of the Second Congo War where militias from the Lendu and Hema communities armed themselves against each other, resulting in an estimated 55,000 deaths between 1999 and 2003.

UN officials believe the conflict amounts to an ethnic cleansing in the province, a point Félix Tshisekedi, the Congolese President, made in 2019 when he called the situation an “attempted genocide.”

Tensions between the Lendu and Hema, the two main ethnic groups in the region, have simmered since colonial time when the country was under Belgium, which is said to have favoured Hema herders with land and political appointments over Lendus farmers. But the Crisis Group, a Brussels-based security think-tank, says in a report that the violence is not simply an ethnic conflict. It noted that the simmering resentments amongst Lendus have since been manipulated by shadowy actors who have much to gain from destabilising eastern Congo.

Ituri is a gold-rich province. The report says locals believe shadowy forces are manipulating the rebels to contest for power and control as seen in the 1999-2003 Ituri war where Rwanda and Uganda threw their weight behind different armed groups.

Human rights abuses fuelling the crisis

Human rights groups including the UN rights agency, have accused soldiers and rebels of abuses that have fuelled the cycle of violence. With dozens of overlapping armed groups operating in Ituri province, accurate figures are hard to come by, but the CODECO is believed to have killed at least 490 people and ADF, 282 people in Ituri since April 2017, according to Kivu Security Tracker, which monitors violence in the region.

A recent report by the UN Joint Human Rights Office (UNJHRO) said 6,989 cases of human rights violations were documented in 2021 in the country, down nearly 12 per cent from 2020.

Around 60 per cent of the violations were carried out by armed groups in provinces affected by armed conflict, where at least 2,024 civilians, including 439 women, were victims of summary executions.

Besides CODECO, other significant armed groups, often acting with total impunity, include the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), Mai Mai, and others.

State agents, including the national army, police, and other security agencies accounted for 35 per cent of the violations, including the extrajudicial killings of at least 40 civilians.

What next?

The current conflict could tip into full scale war if the Hema community organises militias to defend against the attacks on their communities and against other minority ethnic groups aligned with the Hema, the Crisis Group’s report warns.

The UN human rights office has warned there are reports that young Hema men are organising self defence groups and mounting roadblocks in Ituri and of a fledgling rebel group known as “Zaire,” which has set up in Dala, a small village near a CODECO stronghold and gold-mining town called Mongbwalu.

Meanwhile, The Crisis Group has also advised the government to resume dialogue with the militias in Ituri that have already expressed willingness to surrender under the right conditions. “It should also pursue a dialogue with other militias involved in the Ituri violence to pursue their demobilisation. In order to reach a broad consensus on disarmament methods (including on the issue of amnesty), the government should support the mediation efforts of Ituri deputies’ caucus in the National Assembly.”

The central government, it advises, should prioritise the reintegration of rebels into civilian life, particularly by setting up a framework for support and training to provide them with alternative livelihoods.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter