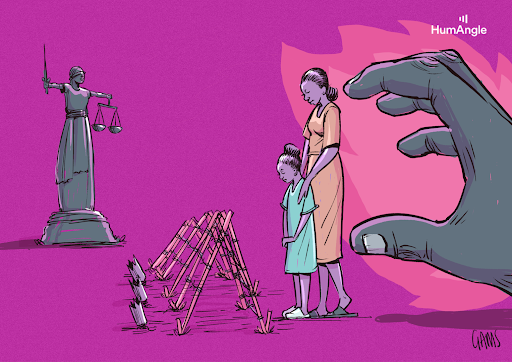

Miscarriage, Childbirth in Jail: The Failure of Nigeria’s Criminal Justice System

The criminal justice system in Nigeria has been criticised for being riddled with mediocrity and systemic flaws. Two women share their miscarriage and childbirth experiences in jail with HumAngle.

She lost her pregnancy in prison in what she describes as “a miscarriage of justice”.

The experience Ayodele Bukunmi had in detention tore her heart apart and still haunts her to date. Now 23, Bukunmi was only 17 when she was thrown behind bars in Ondo State, South West Nigeria. It was October 2020, during the nationwide EndSARS protests against police brutality in the country. On her way to visit a friend in the Akoko-Akungba area, police officers waylaid and whisked her away, alongside protesters.

The police forced her to admit to obtaining flammable materials and causing riots in the state amid the #EndSARS protests, she said. After a few hours of interrogation, they locked her in a crammed cell in the Special Investigations Department of the Ondo State police. Bukunmi insisted she was just a passerby and not a participant in the protest that turned violent, yet, a month later, she was moved to the Surulere prison facility in Akure, the state capital.

For weeks, no one knew she was at the prison facility. She was held incommunicado until her boyfriend, worried about her safety, found out.

She was not alone in this situation; Kemisola Ogunbiyi was also arrested and detained in a similar fashion. Kemisola was on her way to buy drugs for her sick mother when the police picked her up, claiming she was among the #EndSARS protesters.

Kemisola and Bukunmi languished in the Surulere correctional facility with blurry hopes for justice. The duo came from different families and locations, but fate brought them together in a government confinement, where the slow justice system subjected them to torture and inhumane treatment. Interestingly, they both found out they were pregnant while in detention, begging to be given a fair hearing.

The Administration of Criminal Justice Act (ACJA) was enacted in 2015 to reform criminal procedure, promote speedy trials, and protect the rights of suspects, defendants, and victims. However, the criminal justice system in Nigeria has been criticised for being riddled with mediocrity and systemic flaws. With overcrowded correctional facilities, more than 70 per cent of inmates are detained often for years without formal charges or access to legal representation, according to media reports.

A report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) shows how indigent defendants, especially women, suffer disproportionately due to underfunded legal aid and systemic corruption. What the teenage detainees experienced at the correctional facility in Ondo confirms this report. For months, they were held in the police cell without being charged in a court. When the police raided the street and arrested them, they were framed for offences they insisted they knew nothing about. Bukunmi recalled how the officers wrote statements on their behalf, forcing them to confess to crimes they never committed. As hoodlums infiltrated the protests, burning houses and vehicles, including the All Progressive Congress (APC) secretariat, the state authorities unleashed police officers onto the streets to pick up the arsonists; Bukunmi and Kemisola, among others, were scapegoated.

“I was new to Akure at the time and knew nowhere, but they framed me and accused me of arson. They tortured me until I lost consciousness, and at the police station, they didn’t give me any chance to explain myself. I was humiliated and harassed,” Bukunmi said.

When they were finally charged in court, they had no lawyer to back them, and lost their voices before the judge. From the police station, they were moved to an all-female correctional centre in the state, where they would face another level of ill-treatment and dehumanisation.

“They gave us terrible meals – watery beans and lumpy soups. We ate rice occasionally, and our regular stew was simply hot pepper and water. No palm oil, fish, meat, the typically grounded pepper, or tomatoes,” Bukunmi told HumAngle five years later. “I faced hell in detention and still went through hell after I regained freedom.”

The prison officials were cruel and tolerated no one, Bukunmi reminisced. She was once locked in a single, dark cell for over a week, with her legs chained and hands tied for disobeying an officer. She can’t recall the officer’s name, but she described her as “very dark” and newly recruited at the time. Her offence? She hesitated to help the officer clean her shoe. The officer reported her to a superior official, who ordered her to be locked in solitary confinement. They untied her hands once a day to serve her food and water while she was serving the punishment.

“I was still pregnant at the time, and I think these could have contributed to why I had a miscarriage,” she told HumAngle. “The prison space is not for the weak; you could be on your own, and an officer would accuse you of looking at them disdainfully and punish you for no reason. I didn’t really mean to disobey the officer; I was tired and sluggish at the time, and she accused me of hesitating to clean her shoe.”

No detainee dared greet an officer standing, even if they were older, she said. “You must always greet them because if you refuse, that could be a reason to be punished. And you must speak to an officer, you must be on your knees, with your head facing down.”

The ill-treatment meted out on them, experts said, violates section 8(1) of ACJA, which mandates that all suspects be treated with dignity and prohibits inhumane or degrading treatment. The Act also encourages non-custodial sentencing, such as community service and suspended sentences, particularly for minor offences. However, implementation remains inconsistent across states, and many people are still detained in overcrowded, unsanitary conditions.

They were in and out of the courtroom for about eight months without a clear direction, until the story broke in the media in April 2021. Despite getting pro bono legal backing, the court still refused to hear their appeal, aggravating their condition in detention. This slow pace of judicial proceedings worsened their case, further violating ACJA regulations.

The ACJA had introduced reforms like day-to-day trials and limits on adjournments to reduce delays, yet courts remain overwhelmed by case backlogs. A critique published on Academia.edu points out that despite the ACJA’s innovations, poor funding, lack of training, and resistance to change have hindered its effectiveness. Vulnerable defendants often languish in detention while their cases stall, violating their constitutional right to a fair and timely trial.

Foetus lost, baby born in prison

Bukunmi broke the news of her pregnancy to her boyfriend, Balogun Segun, when he visited her in detention. He didn’t believe her initially, but something terrible happened two days later. She started bleeding, and her stomach wouldn’t stop aching. She lost the pregnancy to the daily stress and discomfort she witnessed at the Surulere facility. The pregnancy was four months when she had a miscarriage, leaving her in pain and anguish. Her boyfriend cried out to journalists at the time that Bukunmi had no medical attention, despite her condition.

“She is not being given any medical attention,” he complained. “In fact, the foetus inside her hasn’t been flushed out. She needs help.”

Kemisola also found out she was pregnant in detention, but she scaled through the inhumane conditions. A few months later, she delivered the baby at the facility, catching more media attention. She was one month pregnant when she was arrested and detained in October 2020; she delivered the baby in June and still spent days in detention with the newborn. Her situation sparked social media outrage, with #FreeKemisola trending. Activists and social media influencers pressured the state government until Charles Titiloye, the state’s Attorney-General and Commissioner for Justice, promised to intervene.

A few weeks later, Kemisola was released, gaining public sympathy and receiving donations from well-wishers. The baby was christened and celebrated by notable Nigerians such as Naomi Ogunwusi, the estranged wife of the Ooni of Ife, a first-class monarch in Osun state. Amid the media outrage over Kemisola’s case, however, Bukunmi was left in limbo with no freedom insight. The dead foetus stayed in her belly for months, making her sick. Some online sympathisers protested and moved on quickly. But her mother and boyfriend protested while speaking to journalists, expressing fears that the public might have forgotten the detainee.

“I’m afraid something might go wrong with her in prison due to her health condition,” Iyabo Ayodele, Bukunmi’s mother, lamented. “Help me beg the public not to forget her there.”

She was not allowed to visit a hospital even after complaining on several occasions that her stomach ached badly. At the prison facility, only one matron attended to their medical needs, and she was accused of handling serious issues with levity and sometimes oversimplifying complex health conditions. When she complained bitterly about her aching stomach after having a miscarriage, the matron gave paracetamol, but that changed nothing. She said she endured the pain for months, until she regained freedom.

Three months after Kemisola was released, Bukunmi regained freedom after enduring gruelling complications from the miscarriage. Her life never remained the same, even when she became free. The memory of those moments still haunts her, continually flashing through her mind, she said. When she falls deeply asleep sometimes, she said, she finds herself in a dark dungeon, weeping bitterly to be set free. Other times, she appears in dramatic scenes, dragging matters with the police in her dream.

“Even after I was released, I suffered a lot, physically and mentally. Unknown to me, the miscarriage had affected my womb. But God, time and medical efforts helped me take in the second time,” she added.

ACJA protects the rights of vulnerable women like Bukunmi and their unborn children in detention, but the reality in many Nigerian prisons is different. Section 404 of the Act states that if a pregnant woman is convicted of a capital offence, the death sentence must be suspended until after childbirth and weaning. While this provision offers some relief, it does not prevent pretrial detention of pregnant women, even for non-violent offences. One woman, Fausat Olayonu, for instance, was pregnant when she was detained for stealing a radio set worth ₦20,000. Like Bukunmi and Kemisola, she had no legal representation and had resigned to fate that her unborn child would be delivered in prison. The International Association of Women Judges reports that over 1,700 women in Nigerian prisons are awaiting trial, many of them pregnant or nursing, with limited access to medical care and legal support.

Although the ACJA provides a robust framework for reform, experts, including social justice activists and lawyers, say its impact is limited by weak enforcement and institutional malfeasances such as prolonged detention and inadequate care. Abdullahi Tijani, a lawyer and pro-freedom activist, says bridging the gap between legislation and reality requires stronger oversight, better funding for legal aid, and targeted interventions for vulnerable populations.

“Until these systemic issues are addressed, the promise of justice under the ACJA will remain largely unfulfilled,” Abdullahi argued. “No doubt, Nigeria has proper frameworks to reform its criminal justice system, but compliance is a barrier.”

Ridwan Oke, a Nigerian lawyer and criminal justice activist, says reforming the criminal justice system begins with law enforcement agents, especially the police. During the #EndSARS protest, Ridwan helped facilitate the release of several protesters randomly arrested without a thorough investigation. The legal practitioner said the police need to check their system in terms of arresting people indiscriminately and charging them with ridiculous offences not backed by evidence.

“If the police can always check themselves by not arresting indiscriminately without any evidence, the criminal justice reform becomes easier,” he urged. “Police officers are fond of arresting people indiscriminately, releasing those they can release and charging others to court before looking for evidence.”

He also advised the court to be more critical of cases presented before them, especially cases lacking basic evidence. “Now, anybody can charge anybody without any evidence. That’s bad for our criminal justice system. The court should always put people in critical check and reduce bail conditions for lesser offences so that there would be no delay in justice delivery.”

Ayodele Bukunmi, detained during Nigeria's #EndSARS protests, suffered a miscarriage in prison, highlighting flaws in the criminal justice system. Along with Kemisola Ogunbiyi, she was falsely accused by police, endured inhumane treatment, and denied legal representation in overcrowded facilities. Despite the Administration of Criminal Justice Act aiming for reform, poor implementation and systemic corruption leave many detainees without fair trials or adequate medical care. The case underscores the need for strong law enforcement reforms and a justice system equipped to protect detainee rights effectively.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter