Maitatsine: The Preacher of Fire (1927 – 1980)

Preaching a puritanical and violent form of Islam, Maitatsine attracted thousands of disaffected youths, mostly almajirai, whom he radicalised into a cult-like movement. In December 1980, his ideology culminated in one of the deadliest urban uprisings in Nigerian history.

It begins with the memory of smoke.

Hadiza Yahaya, now in her late 70s, folds her shawl over her shoulders as she leans forward on the mat in her compound in Jakara, Kano State, northwestern Nigeria. Her voice is heavy not from age, but from the weight of the past that even time hasn’t been able to lift.

“I was pregnant with Mukhtar,” she recalled, narrating it as if it happened yesterday. “I had just picked up dry pepper and baobab leaves in Rimi Market when the shouting started, and then people were running.” It was the kind of shouting that didn’t come from mouths. It came from something deeper: from the chest, from the soul, and from the feet running helter-skelter.

December 18, 1980.

A date seared into the Kano skin as though with a branding iron. That day, the city turned into a battlefield. It was the day Maitatsine declared war not with a foreign army but with an ideology brewed in the underbelly of forgotten slums.

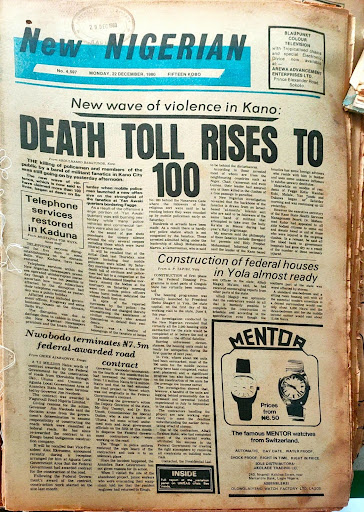

The then leading newspaper in Northern Nigeria, New Nigerian, reported that four police units had been sent that day to Shahauci playground, an open space where Maitatsine and his fanatics gathered, to arrest some of his followers for preaching without permits. Upon arrival, the police were ambushed suddenly from all directions, by people wielding hatchets, bows and arrows, swords, clubs, daggers and other similar dangerous weapons.

Gaskiya Ta Fi Kobo, a local Hausa newspaper, documented that on the first day of the violence on Thursday evening, “[N]ine police vehicles were burnt and four officers were killed. Traffic in Kano on Friday and Saturday was at a standstill as people feared being caught up in the chaos. Even health workers were not able to go to the hospital, and everywhere in the Kano city and Sabon Gari area were deserted.”

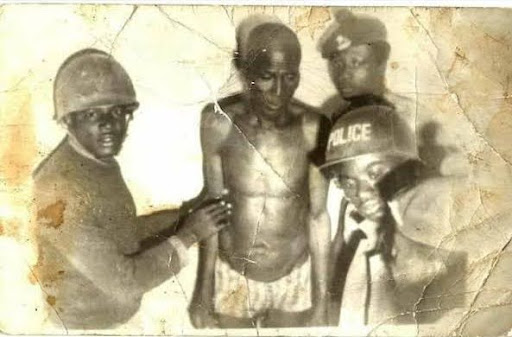

The first wave of the violence lasted with about a hundred casualties, most of them civilians, and the second one came after the police invaded Maitatsine’s home in Yan Awaki within the Kano Municipal. The violence lasted 11 days, with a conservative number of 4,000 people killed, including Maitatsine himself and excluding the military and the police. At the end of the violence, Maitatsine was fatally wounded, and his followers took him from the Koki through Jakara-Goron Dutse and then settled at Rijiyar Zaki, where they buried his corpse before it was dug by the authorities to confirm his identity.

Maitatsine was a fiery Cameroonian-born Islamic preacher who settled in Kano and rose to infamy for his extremist sermons that denounced modernity and mainstream Islamic scholars. Preaching a puritanical and violent form of Islam, he attracted thousands of disaffected youths, mostly almajirai, whom he radicalised into a cult-like movement. In December 1980, his ideology culminated in one of the deadliest urban uprisings in Nigerian history, leaving over 4,000 people dead in an 11-day conflict that devastated Kano city.

More than four decades after his death, the ghost of Maitatsine still haunts Northern Nigeria, not through his body, but through the unresolved crises that birthed him. The 1980 uprising in Kano was not an isolated explosion of religious fanaticism; it was the violent manifestation of deeper structural failures. Today, the same volatile conditions persist, allowing Maitatsine’s ideology to live on in new, more dangerous forms. His fire may have died, but the kindling remains all around.

“When they were passing through Jakara to their final destination, we could all hear them shouting that Mallam, meaning Maitatsine, had ordered that no one should turn back. They were chanting ‘ban da waiwaye’ (don’t turn back) until they passed carrying him,” Hadiza recalled.

The old woman said that the 11 days of Maitatsine violence were the most horrific conflict she had ever witnessed. “Not even Boko Haram is at this scale,” she said. “Imagine thousands of people being killed within that short period, not with bombs or guns, but with arrows, swords and even sticks.”

The whisper before the fire

His name was Muhammad Marwa, but people no longer remember him by that name. Instead, they used the terrifying title: “Maitatsine”—which in the Hausa language means “He who curses”, because Maitatsine cursed a lot. He cursed watches. He cursed bicycles. He cursed radios and televisions. He cursed all innovations brought by modernity and considered them satanic and ungodly.

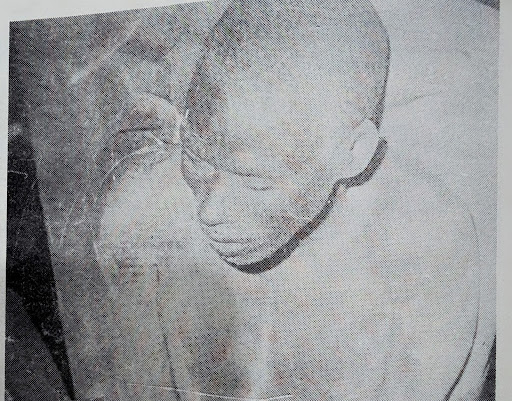

“Allah ta tsine (God has cursed),” he would say in his poor Hausa, corrupted by his Fulfulde accent. He was said to be slim, tall, and dark in complexion. He was one-eyed and the other had a squint. He memorised the Qur’an by heart, and he felt it was his duty to fight the then predominant Yan Darika – The Sufis.

And so, the man who once came from Cameroon to Kano in 1955 and settled in Gwammaja before moving to Yan Awaki as a seeker of knowledge transformed into the leader of a bloody rebellion in a city that welcomed him, gave him home, and family; a preacher turned executioner who washed his hands not in water—but in blood.

In 1962, his provocative preaching, which centred around condemning modern inventions like radios, wristwatches, and medicine as satanic, and rejecting all scholarly interpretations of the Qur’an, and declaring anyone who owned such items or disagreed with him as unbelievers, was reported to the authorities and that led to his arrest, imprisonment and subsequent deportation back to Cameroon, but he somehow sneaked in and came back just a year later after the then emir, Muhammad Sanusi I, who sentenced him was dethroned.

However, between 1966 and 1975, Maitatsine, along with other preachers, were accused and found to be dangerous preachers, and again sent to prison in Makurdi, Benue State, under the then military governor of Kano state, Audu Bako. Maitatsine was detained for “showering abuses and making slanderous and irresponsible speeches capable of inciting violence against the Governor, the Emir, and other important personalities in Kano State,” according to the police report seen by HumAngle.

His return was more prepared and strategic. His hostile dealings with his neighbours in Yan Awaki, and the subsequent killing of his son Tijjani, also known as Kan’ana, allegedly by his friends at a beer parlour, led Maitatsine to become more violent and paranoid.

His followers started carrying arms to the preaching ground in Shahuci, and their speeches turned more violent in 1979. People living around his house in Yan Awaki reported many cases of assaults and encroachment of private and public properties, including stalls and two public schools.

Within those years, people accused Maitatsine of abducting and brainwashing their children, who were mostly youths and boys in their early teens and some even 11 years old.

“Children would be found missing and after thorough investigation, they would be found at Maitatsine’s residence, and if asked to come back home, they would refuse,” said Mallam Sani from Dambazau, 65, born just a few meters from Yan Awaki.

Towards the end of November 1980, barely two months before the full carnage, Maitatsine and his fanatics resisted military and police arrests with crude weapons and apocalyptic beliefs. And when the full violence erupted in December, the carnage was Biblical: bodies littered the streets and smoke blackened the sky.

When the Nigerian military finally entered, Maitatsine was fatally wounded and finally lay dead; his corpse was consumed in the violence he started.

But a preacher does not die with his body. He dies only when his memory is disarmed.

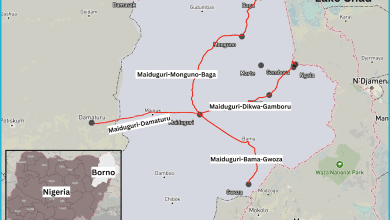

Maitatsine’s movement, though crushed in Kano, metastasised like cancer. In 1982, violence erupted in Maiduguri. In 1984, Jimeta. In 1985, Gombe. His ghost wandered from slum to slum, whispering to other angry souls. It was in Borno that his ideology found its most dangerous inheritor.

Muhammad Yusuf and Abubakar Shekau, decades later, would echo Maitatsine’s rejection of modernity. Boko Haram, a phrase meaning “Western education is forbidden,” was not new. It was a reincarnation of Maitatsine’s sermons—only this time, with guns and suicides.

A problem that never ends

But perhaps this is not merely the story of a man. It is the story of a city that simmered too long in the fires of poverty and abandonment until it exploded, and no lesson was ever learnt.

“Most [Maitatsine] converts were illiterates and semi-literates drawn from the neighbouring West African States of Niger and Mali as well as from Chad and Cameroons,” wrote Nasir B. Zahraddeen in 1983 after investigating the violence then as a reporter with Nigerian Television Authority (NTA) and BBC Africa Service.

His followers were not just from Kano or Nigerian states. The report of the post-violence tribunal counted the non-Nigerian fanatical followers of Maitatsine as captured by the police as 162 Nigeriens, 16 Chadians, 4 Camerounians, and one from Burkina Faso, then known as Upper Volta. The tribunal then explained that among the major causes of the disturbance was Maitatsine’s ability to gather a “build-up of contingent of armed students styled as almajirai” who were willing to submit themselves for a spiritual exchange.

Forty-five years later, in 2025, the bomb is still ticking.

In fact, little has changed in substance, even if the language has evolved. Where the 1980 Commission of Inquiry cited “uncontrolled influx of almajirai and itinerant preachers” as enabling Maitatsine’s rise, today’s government statements often use phrases like “out-of-school children” or “street begging”. The language has shifted, but the boys are still there.

The numbers tell their own story. In 1980, estimates of almajiri children in Kano hovered around a few hundred thousand, a demographic largely ignored by official schooling statistics. By 2025, despite billions in federal interventions, presidential declarations, and donor-funded pilot programs, UNICEF estimates suggest that over 1.2 million almajiri children still exist across Northern Nigeria, with Kano State contributing the largest share.

Back in 1980, Maitatsine found in the almajirai a ready-made army: poor, disenfranchised, and already indoctrinated into a harsh, rigid version of Islam that mistrusted Western institutions. Today, extremist groups from Boko Haram to ISWAP continue to target similar children for recruitment. The methods may be more sophisticated, the messaging encrypted in apps and videos rather than shouted in slums—but the vulnerability remains the same.

What is perhaps more damning is that the almajiri system has survived not because it is effective, but because it is politically untouchable. Every administration since the Maitatsine crisis has promised to reform it. The Obasanjo-era UBE policy, Jonathan’s 2012 “Almajiri Education Programme” (which built over 100 almajiri model schools, most now defunct or converted into conventional schools), and even Buhari’s rhetoric on integrating almajiri into formal education have all fallen short.

In Kano, the 2020 lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic briefly forced some almajiri children off the streets, but no sustainable reintegration followed. As of 2025, the streets of Kofar Wambai, Sabon Gari, and Rijiyar Lemo still echo with the chants of barefoot children asking for money and leftover food in the name of survival and vulnerable to another Maitatsine recruiting them.

What makes this persistence even more tragic is that the Maitatsine violence was not merely a religious uprising; it was a cry from the margins. A desperate reaction from a class of people who felt abandoned by both their leaders and their society. Yet today, the same conditions remain: urban poverty, unregulated religious authority, a failing educational alternative, and a generation of children condemned to life on the fringes.

The unhealed wound

The 1980 Maitatsine uprising brought to light a deep-seated and dangerous sectarian divide within Kano’s Islamic community, as meticulously documented by the official tribunal report. It observed that “followers of some of the movements were not accommodating enough to respect the religious views held by others outside their groups.” This wasn’t merely an academic theological disagreement; it represented an ingrained culture of mutual suspicion, open verbal attacks, and theological exclusivity.

This hostile environment created incredibly fertile ground for the eruption of violence. The emergence of various fringe sects, such as the Yan Izala (Salafists), Qadiriyya, Tijaniyya, and later, the radical followers of Maitatsine himself, was characterised by their explicit refusal to coexist peacefully with other interpretations of Islam. The core of their dispute was not about the nuanced interpretation of sacred texts, but rather a fierce contention over legitimacy: who truly spoke for God, and who, by extension, did not.

“We have failed to build a culture of religious pluralism, even within Islam,” said Mallam Muhammad Mustapha, an Islamic scholar in Kano. “When every group believes it alone holds the truth, conflict is not just probable, it is inevitable.”

Now, in 2025, while the specific ideological fault lines may have subtly shifted, the underlying spirit of intolerance stubbornly persists. Kano remains a vibrant yet precarious mosaic of competing Islamic ideologies. Major groups like the Izala (Salafiyya), various Sufi orders (Qadiriyya, Tijaniyya), and the growing Shi’a community, alongside newer reformist groups, all coexist in a state of uneasy tension that often leads to accusations of blasphemy and verbal attacks.

In January 2006, a fiery sermon by a preacher in the Dorayi area sparked clashes between Izala adherents and Tijaniyya youths. The preacher had called the Sufi practice of invoking saints “shirk” (polytheism), prompting retaliation. Police made several arrests, but the underlying tension remained.

The advent of social media has dramatically amplified these divisions. Preachers now leverage platforms like TikTok, YouTube, and Facebook to publicly denounce one another, often employing highly inflammatory rhetoric that further polarises their followers. Disturbingly, in some Friday sermons, the “other” is no longer just deemed incorrect; they are explicitly labelled a “kafir” (infidel), “zindiq” (heretic), or “mushrik” (polytheist), designations that can have severe real-world consequences and incite violence.

In a viral video from late 2024, a social media extremist preacher named Muhammad Muhammad condemned other preachers as “unbelievers for practising or participating in democratic activities.” This has created counterattacks, especially on social media, leading to banning him from preaching and closing his mosque, but he later continued with an even more volatile narrative.

Just as in 1980, this pervasive theological balkanization continues to render any form of constructive, peaceful dialogue nearly impossible. This fragmented religious landscape makes the youth particularly susceptible to extremist interpretations, especially when those interpretations offer tempting promises of spiritual superiority, divine favour, or even political revenge against perceived enemies.

“We are seeing young people radicalised not in the bush, but in their bedrooms with a smartphone,” said Babagana Abubakar, a counter-extremism specialist. “The new battlefield is digital, and the consequences are real and bloody.”

Urban migration and youth unemployment

The tribunal report astutely highlighted the “lack of job opportunities in rural areas” as a significant driver, forcing countless young men to flood into bustling urban centres like Kano. However, upon arrival, many of these migrants found themselves unemployed, idle, and consequently, highly vulnerable.

Today, the urban-rural imbalance has grown even starker and more pronounced, with an over 75 per cent poverty rate in 2025. Northern Nigeria continues to grapple with one of the highest youth unemployment rates on the entire continent. The situation is exacerbated by escalating terrorism and insecurity in rural areas, which have rendered traditional farmlands unsafe and unproductive, further accelerating the desperate exodus of young men from villages to cities already groaning under immense population pressure.

In March 2024, a mass displacement from Katsina’s rural areas, triggered by repeated attacks by armed groups, led to many youths arriving in Kano. The state’s emergency response was overwhelmed. By May, reports surfaced of rising petty theft such as phone snatching and gang formation around the Rijiyar Lemo axis.

The dreams that initially brought these youths to Kano, often fueled by hopes of economic betterment, frequently die quickly in the face of harsh urban realities. In this profound vacuum of opportunity and hope, charismatic preachers, criminal gangs, and extremist recruiters readily step in, offering a sense of purpose, belonging, and often, a means of survival, albeit through illicit or violent avenues.

What Maitatsine so effectively exploited in 1980, a vast pool of idle, frustrated, and disaffected youth, is even more available and primed for recruitment today, compounded by the profound disillusionment of an entire generation that feels increasingly cut off from the promises of both the state and established religious institutions.

“Hopelessness is a currency in which insurgents and extremist ideologues trade,” observed Abubakar. “And in cities like Kano, the market is flooded.”

Decline of traditional authority

Finally, the tribunal explicitly cited the “emasculation of the authority of traditional rulers” as a core contributing factor to the crisis. In the pre-colonial era, and even during the early colonial period, emirs and district heads held not only considerable political sway but also significant traditional authority. They possessed the power to approve or restrict preachers, mediate and settle theological disputes, and enforce religious norms within their domains. This system provided a crucial layer of regulation and oversight for religious activities.

However, by 1980, this traditional authority had been severely stripped or heavily politicised, largely due to colonial restructuring and subsequent military governance. Maitatsine shrewdly thrived in this resultant regulatory vacuum, establishing his base in Yan Awaki with little to no meaningful interference until his movement had grown dangerously large and violent. In 2025, the situation has, if anything, worsened considerably. Traditional rulers largely remain ceremonial figures, frequently sidelined in critical political and religious decision-making processes.

In 2017, the Emir of Kano’s attempt to find solutions to the family crises through women’s empowerment was largely resisted from the pulpits. Another incident of how an ISWAP operative found a home in Kano and bought properties in 2021, bypassing the local traditional leaders, has further exposed how traditional institutions have become largely toothless in reigning in any excesses.

Preachers now gain influence and a following primarily through digital platforms like TikTok rather than through the approval or vetting of traditional authorities symbolised by the turban. There is a marked absence of any centralised, legitimate authority capable of effectively vetting emerging ideologies or reining in dangerous fringe movements. When an individual begins to gather a cult-like following in a remote corner of the city or through online channels, there is often no coherent or effective system in place to monitor their activities or intervene before a threat materialises.

“The Emir once had the power to license a sermon. Now, the algorithm does,” said Faruku Muhammad, Wakilin Arewa, a traditional leader. “And the algorithm does not ask who you might hurt.”

This pronounced decentralisation of religious authority is inherently dangerous, not because centralisation is flawless, but because the absence of effective checks and balances allows dangerous, divisive, and extremist ideas to proliferate and spread largely unchallenged, mirroring the very conditions that allowed Maitatsine to flourish in 1980.

Gone – not with the matchbox

Hajiya Hadiza’s son, Mukhtar, now 44 and works as a tailor, was born in the same week Maitatsine died. “Sometimes,” he says, “it feels like my mother gave birth to me in violence, and I’ve always been remembered with Maitatsine’s violence.”

Maitatsine’s carefully reserved ash, after his corpse was burnt, now sits at the police laboratory in Kano. He is gone, but left behind some bitter memories.

If Maitatsine was merely the manifest symptom of a deeper malaise, then the insidious disease itself—characterised by profound social alienation, relentless doctrinal conflict, and pervasive state neglect—has, regrettably, never been truly cured.

The preacher of fire may be gone. But the matchboxes remain.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Muhammad Sanusi I was dethroned under the Abubakar Rimi administration.

The article details the 1980 Maitatsine uprising in Kano, Nigeria, led by extremist preacher Muhammad Marwa, known as Maitatsine. His rejection of modernity and radical Islamic beliefs led to a violent rebellion, resulting in over 4,000 deaths. Decades later, the conditions that allowed his ideology to thrive remain: urban poverty, youth disenchantment, and lack of effective authority. These issues have enabled similar extremist movements like Boko Haram to proliferate, as socio-economic disparities and unresolved crises continue to fuel radicalization among vulnerable youth in Northern Nigeria.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter

Pungent, relevant & captivating. I didn’t drop it until I finished reading. This tells the story in the South East presently. We’re living a lie by deceiving ourselves as to the origin of insecurity in our region. Nnamdi kanu is the Maitatsine of our time and is using many uninformed and impoverished youths in committing heinous crimes against the state. I laugh when they call him a freedom fighter and claim he hasn’t done any wrong. He’s a criminal and should be punished. If allowed to go free, I promise worse criminals would emerge that would divide and dissect this country into so many parts we would loose count.