Lost Homes And Herds: The Anguish Of Nigeria’s Arab Community

The Boko Haram insurgency in the Lake Chad region has displaced many rural Shuwa Arabs and led to the loss of their ancestral livelihood of herding cattle.

A herd of cattle was out in the field one afternoon when Boko Haram insurgents stormed the area and fired gunshots. Suddenly, the herders looking after the animals found themselves running for their lives while the insurgents went away with an estimated 300 cattle.

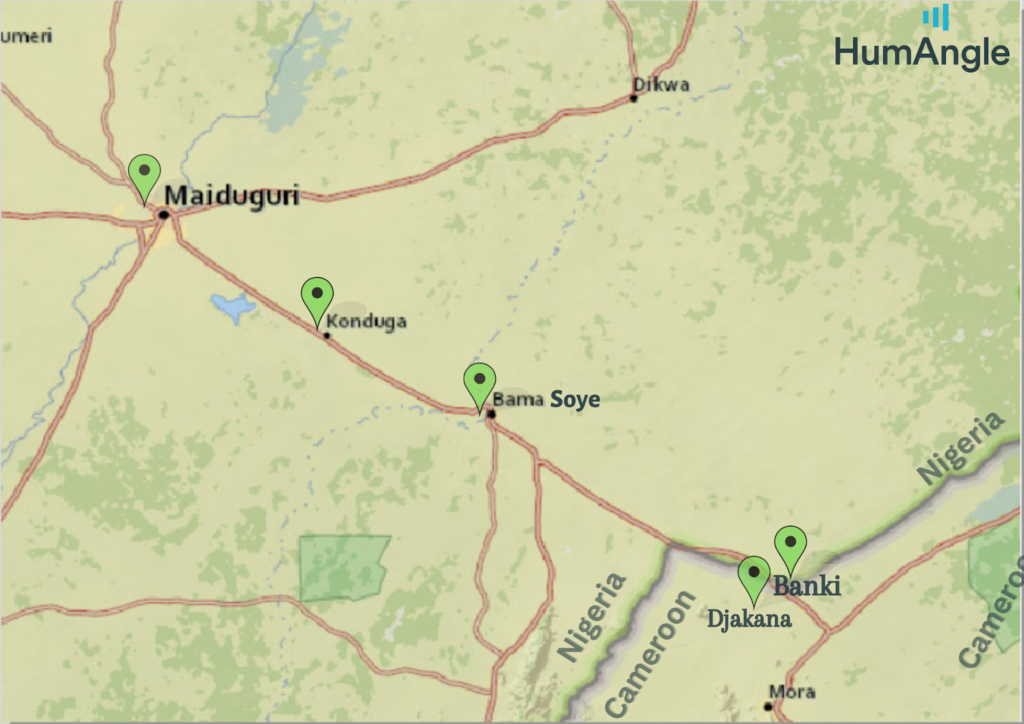

The incident is one of many involving the rustling of livestock belonging to displaced Shuwa Arabs living in Mashi Mari, a community in the Konduga Local Government Area (LGA) of central Borno. “What has happened to us is very heavy,” narrates 65-year-old Bulama Adam.

The Shuwa Arabs, also referred to as Baggara, are of Arab descent and speak a dialect of the Arabic language. They are mostly-nomadic cattle herders found in parts of the Lake Chad region ravaged by the ongoing Boko Haram insurgency.

From here on, life has ended

Adam’s previous life was good, he remembers. “Before, there was nothing beyond our strength in life.”

He grew up in Gabari village in Bama LGA and recalls having animals and food reservoirs of grains in many underground storage pits. It was an era when the necessities that shape living conditions were available. “We had thousands of bags of food; there was nothing beyond our capacity.”

They had enough to meet their needs and those of others. But now, they are in a tough predicament and face overwhelming hunger.

Seven years ago, Adam’s family decided to flee Gabari with 513 cattle and over a thousand sheep and goats. Initially, they lived alongside the insurgents, despite their austere rules, until a relative was shot and killed because he smoked cigarettes.

They sought refuge in the neighbouring Republic of Cameroon for a time. Then they returned to the town of Banki, near the border, after getting told to return to Nigeria. However, the new location was also unsafe; a Bulama was killed, and the insurgents stole over 200 cattle.

They later headed for the main town of Bama after soldiers stationed in Banki told them they could not guarantee their safety, likely because of the threat looming nearby in the infamous Boko Haram Sambisa forest stronghold. Since last year, the security environment in the local government area has mutated after the Islamic West African Province’s conquest of the forest.

The journey to safety did not stop in Bama, and they had to move to Konduga on foot alongside their animals after getting instruction from soldiers to do so. “We didn’t know this place. The soldiers brought us and told us to stay. Our choice was Cameroon, but it was from Cameroon that we were chased away,” says Adam, seated on a mat spread in a round thatched structure.

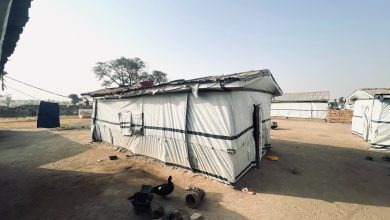

Several communities in Borno have either been deserted or destroyed, with over two million displaced due to the insurgency. These displaced people find shelters in official camps or communities such as Mashi Mari, where they confront the daily anguish of the insurgency.

“From here on, life has ended.” This is how Adam describes the shift from his former condition and the current challenges. He gets to feed from the monthly food aid and the produce from their farm.

He still has three cattle from what’s remaining of the family’s herd.

Abdullahi Alhaji Kosheri, who speaks bits of English he picked up during the days of trading south of the country, had a similar experience. Seven years ago, he also fled his village of An Doguno to Banki, then Cameroon, and back to Nigeria due to reports of herders getting killed and animals being rustled.

The 60-year-old husband of two wives and father of 12 says before Boko Haram, life was going okay. He harvested 70 bags of grains annually and had food for an entire year. When there is a need, he could sell one of his 70 cattle.

After fleeing to Banki, he says they were told that staying there was dangerous and that they should leave for Cameroon. Yet, the situation took a sharp turn when a bomb exploded in a town called Djakana. In response, the residents told the military to take them away. The locals told their women who sold milk at the market, “we don’t want to see Nigerians; they brought these things here,” referring to the Boko Haram threat.

They went to Banki, but the security conditions were not favourable because Boko Haram was close-by and they would come for the animals. Afterwards, they walked a long distance with their cattle and slept in a town called Darul Jamal. They later moved to Soye with a military escort, then Bama, before winding up at their present settlement in Konduga.

Then the animals began to go missing.

“We came here, we grazed our animals and returned. Today 100 gets taken, tomorrow 200, next 300; that’s how the animals were stolen,” wails Kosheri. Now, they have few animals around. Thanks to the food aid and proceeds from the sale of firewood, they have started buying sheep, while some have brought cows and started rearing again.

Through his earnings from the firewood, he could buy two sheep that gave birth and brought his livestock number up to seven.

When Boko Haram insurgents stole the cattle belonging to 45-year-old Saleh Muhammad, they informed soldiers and a chase to recover the animals followed. Sadly, he watched them disappear as the insurgents crossed a river.

The father of 10 depends on the monthly aid supply and collecting and selling firewood. He avoids areas with the insurgents, explaining that “several people have been killed fetching firewood.”

The insurgents are not only notorious for taking away cattle and targeting farmers. They have also killed people fetching firewood in forest areas.

The community members’ stories revolve around the loss of their homes and livelihood inherited from their forefathers. Adam Muhammad, 38, originally from a different section of Doguno, used to have 65 cattle and plenty of sheep. When he arrived in Banki, most of the animals got lost after the soldiers fired shots. The incident scared the animals and they fled.

For Bulama Isah Kamsollum, it was almost six years ago when 142 of his cattle were stolen in a day. Before then, he had also lost 26 during the journey to Konduga. Now, he has the sheep and goats they bought.

The 53-year-old fled his home in Gujjari after two people from Giro town attempted to flee and were caught and punished in front of them. “At that moment, we also decided if we got the opportunity, we should escape,” and the chance came. He went through the same routes travelled by Kosheri.

Boko Haram sent four suicide bombers to Mashi Mari, the latest being three years ago.

Resisting

Self-defence groups have sprung up over the years to protect communities and assist government forces in counter-insurgency operations. They consist of volunteers armed with weapons ranging from sticks, pump action, and assault rifles.

Before the insurgency, Eli Ngaji farmed and reared livestock and farmed. The 50-year-old was part of the early resistance in Gabari against Boko Haram, employing Dane guns usually used for hunting.

He fled the community eight years ago, feeling his life was at risk. The situation had become tough, leading him to leave his family and everything for Maiduguri. His possessions, including livestock, were subsequently carted away.

The Ngaji family would later join him after fleeing to Gamboru Ngala at the outset. When they reunited, he constructed a shelter in the Konduga settlement because staying in Maiduguri would be challenging due to the cost of living in the capital.

“We are living by the grace of God,” he says.

“We all survive with monthly aid. No farming here; what people only think about here is what to eat.”

Most people, including Ngaji, came with animals, but gradually, many were taken away. This has further increased the community’s difficulties as they have lost an important aspect of their life passed from generation to generation.

While still waiting for our transport back to the capital, he points into the distance. “Over there is where Boko Haram insurgents move around,” he observes. Beside us is an unoccupied guard post near the road connecting Konduga and Bama. Not far also is the trench that is often the line between government-controlled areas and areas facing higher insurgent threats.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter