Losing A Toe To Military Brutality And A Family To Insurgents

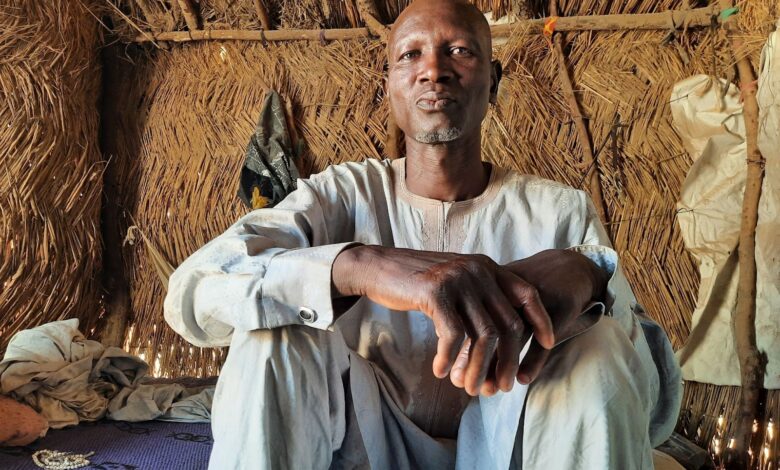

One minute, Aja Kaye was having breakfast with his wives and children and all was right with the world. Then everything changed.

If it were not for the insurgency, Aja Kaye would likely have all his toes intact.

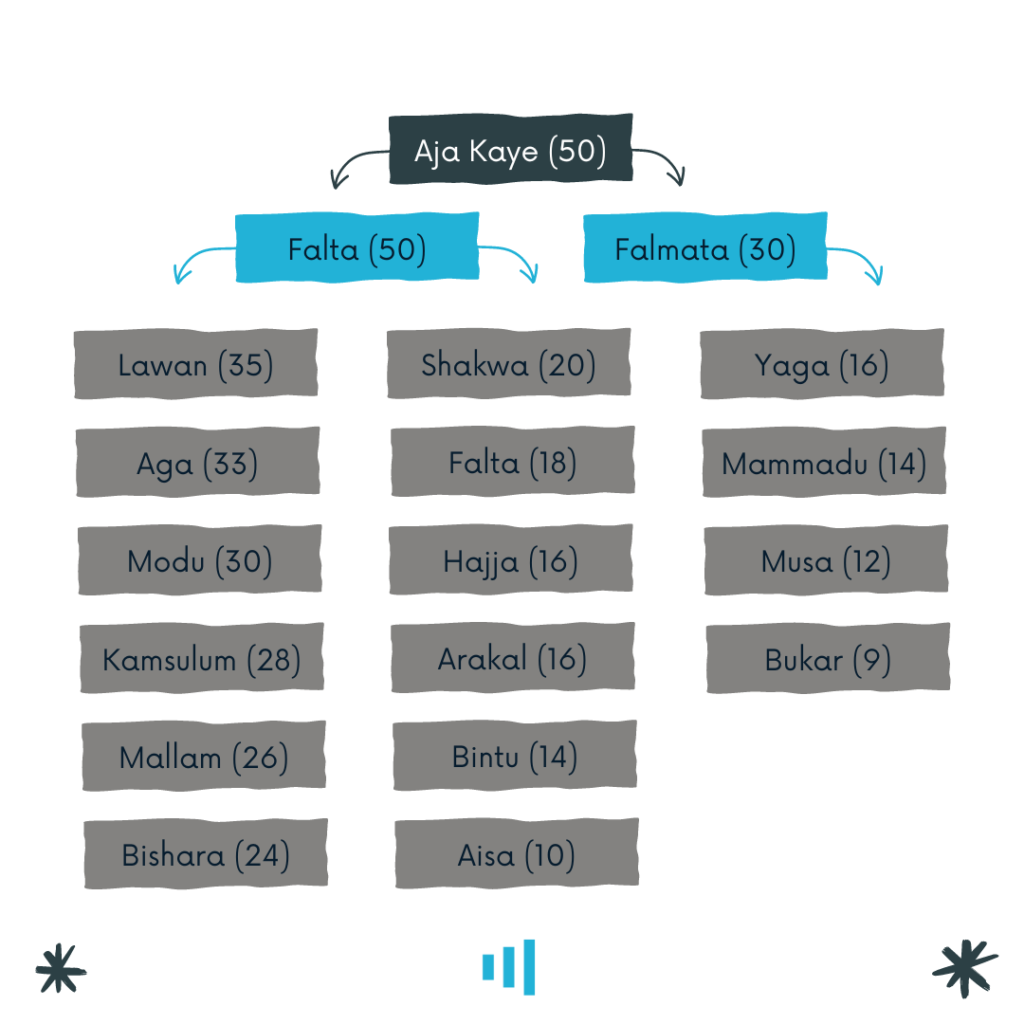

His brother, Ali Mallam, would be alive. His two wives and 16 children would be with him, and not the terrorists in an area beyond his reach. But the insurgency happened — is still happening — and Aja’s little toe, sibling, and family are all gone.

Boko Haram’s 2009 uprising in Maiduguri, northeastern Nigeria, flung open a Pandora’s box, which, to this day, is a source of misery to many. The violence that erupted has shattered thousands of households and destroyed millions of lives, its ripples are felt not just in the region but across the world. Nearly 2.4 million people have been uprooted from their homes. Nearly 350,000 have been killed by the chain of events. More die by the day. Even though many of the victims have managed to escape the growing death toll, their lives have become mangled beyond recognition.

For 50-year-old Aja, everything changed one morning seven years ago. He’d just had breakfast with his family and was preparing to go to the farm in Jinaba.

Jinaba is a tiny village in the Dikwa Local Government Area of Borno. The people spoke one language and had the same culture. Everyone knew each other. They used to stay in one location, but as they continued to farm, some cleared bushes in the area and relocated closer to their farmlands.

There had been a military operation in July 2015 to wrestle Dikwa town from Boko Haram’s tight grip. Afterwards, soldiers stayed back to ensure the place was rid of insurgents. But in carrying out their duty, the military personnel treated civilians with great suspicion, indiscriminately arresting locals, especially male residents.

“The day after they chased Boko Haram out of Dikwa, they went on patrol to our village,” Aja recalls. “Two military vans parked in front of our house. They arrested four of us and accused us of being Boko Haram members. They took us to Dikwa [town] and, from there, Giwa barracks.”

The three others arrested were Aja’s brothers. And the minutes he spent having breakfast that morning would be the last time he saw his family.

The four brothers were held in Dikwa town for nearly three months. The soldiers blindfolded them, tied them up, and tortured them in hopes of wringing a confession from their breath. They spread them under the sun, their chests against the ground. It was hot. The temperature reached as high as 35.6°C, over eight degrees more than Nigeria’s average yearly temperature.

The men were in this excruciating position between around 11 in the morning and 4 p.m. Aja says, on top of that, the soldiers continuously hit them with hefty sticks. Ali Mallam, his 30-year-old brother, did not survive that day.

He himself has countless scars from those weeks at the Dikwa military base. His hands became swollen where he was tied as if water had been pumped into them, and then it developed into a permanent injury. The military offered some treatment — getting someone to inject them twice, but it wasn’t enough. In the weeks that followed, the soldiers fed them but also got them to clear bushes, fetch water, and engage in other chores. Aja and his brothers could not partake because of their injuries.

“It is because of the time they tied me I became sick like this,” he says, raising his right sleeve and pointing to the raised, shiny scars on his arm. Later, he would point to similar scars on his left arm and his back. He sustained the greatest injury on his right leg and could not walk for a long time. He still cannot walk without limping.

In this condition, he was transferred to the Giwa barracks, a military detention centre in Maiduguri infamous for holding thousands of people without trial and in inhumane conditions. Amnesty International estimates that up to 10,000 detainees at the facility may have died between 2011 and 2020. Many of these deaths were due to “severe overcrowding, scarce food and water, extreme heat, infestation by parasites and insects, and lack of access to adequate sanitation and health care”.

Aja was here for six and a half years. He remembers there wasn’t enough water or food. The cell was congested, and inmates could not stretch or sleep properly. Instead, they sat on their buttocks, their soles on the floor, and their legs forming an inverted V. “So many people died from heat and congestion. For four years, I slept in this position until they built new cells where we could lie down.”

But there was something else that bothered him.

“Because of the congestion, people constantly marched on the wound on my leg,” he says. “It got worse and became like this. It started to rot and stink. You would see insects inside. Everybody was avoiding me because of the smell. The bones were broken and one was even sticking out.”

Asked if he got any medical attention at the barracks, his ‘no’ was swift.

Aja was one of the hundreds of detainees released by the Nigerian authorities in July 2021. One of his brothers, Ali Kaw, 40, was released earlier in 2020, and the second, Mallam Koma, 60, remains in detention. The Army confirmed that the men released last year were not Boko Haram fighters and, following its investigations, had not been implicated in terrorism and insurgency. Despite this acknowledgement, the former detainees were treated poorly, denied access to displacement camps, and were not given any compensation for their ordeal.

“They were not given one kobo. In fact, most of the men were wearing singlets; some of them don’t even have shoes on,” one source told HumAngle. “The women had to go round to look for slippers and shirts to give their husbands before they paid a taxi from the [rehabilitation] centre to the IDP camp. The seven men [directed to Banki] don’t even have transport money to go as of this morning. They are trying to beg and see if they can get transport fare to travel to meet their wives.”

Aja too hasn’t received support from the government despite his unique circumstances. “They didn’t give me anything,” he says twice for emphasis. It was his brother who supported him with money to transport himself from the detention facility.

“My major problem is my leg which I still go to the hospital on my own to treat for the past four months. I go to dress it every week. They said I have to do some tests for the surgery, which I cannot afford. So I need assistance on that to enable me to continue the treatment.”

He adds that the surgery should cost about ₦200,000 ($450), including money for medication and admission at the hospital.

Meanwhile, as other released men struggled to reunite with their wives and children, shocking news awaited Aja. His family was completely gone. People from Jinaba said they had left them in the village. But the community is now known to be deserted.

“I was expecting to meet every one of them. But I have searched Mafa, Bama, Dikwa, and many places and haven’t seen them up to now,” he says.

He later learnt that his family relocated to the Sambisa Forest area southeast of Maiduguri, a place notorious as a hideout for Boko Haram insurgents. When he sent word to inform them of his release, he got yet another shock: They were not willing to return.

Ahmadu Aga, former district head of Jinaba, says after Aja’s release, some women were visiting the Sambisa Forest area. So they sent a message to Aja’s family.

“We told them Aja Kaye has come back, so you have to come, please. The women returned with a message. The family told them that they heard there was no food here. ‘We are a large family; how can we go without food? We can’t stay there because there is no food.’ The wife said, ‘Let him [Aja] try and join us.’ But Aja Kaye cannot go there.”

Ahmadu learnt that Falmata’s brothers had joined the insurgent group. So they seized her with the excuse that “her husband had gone to the land of the unbelievers” and she didn’t have to wait. Then they took her to Yale and married her to one of them. Falta followed with her children during the farming season.

“We are always asking people in the bush to come back. We tell them to come. But up to now, we don’t have updates from his family,” says Ahmadu.

Aja is more cheerful when he talks about his family, especially his older wife, Falta. Falta is tall, fair, and has the Kanuri tribal marks. Falmata is the opposite: short, dark, and without facial scarification.

He misses them, he says. It is clear from the way his eyes glitter he can’t wait to see them again.

He met Falta as a teenager. She was young too. Their parents arranged their marriage without really consulting them. What was the first thing he liked about her? “She was always obedient,” he replies, smiling almost sheepishly. “She didn’t offend me or do something bad to me. I missed her when I was in detention.”

“You know, when we were there, we lived happily and cracked jokes together. They cooked all that I wanted. They took care of me,” he says about his wives. “Now that I am back, it is other people who are helping me with food. I have become a burden to others.”

As he recites his 16 children’s names, his smile widens. He rocks back and forth as someone lost in a daydream.

Without them, life as a displaced person is even tougher. Because of his age and injury, there is little he can do to fend for himself. Many other IDPs survive by fetching firewood from forests in the area and selling the fuel, but Aja cannot join them. He depends on others for food. Even the tent he stays in at the Muna Garage el-Badawi displacement camp isn’t his.

But these challenges won’t deter him from getting his family back. If he could send them a message, he hints, he would tell them he has a room and enough means to take care of them.

“I am always thinking about them,” he says, smiling as he wards off flies buzzing around his right leg. Then the smile fades away like it was never there.

“—But it is sad I can’t see them.”

This report was produced in partnership with the Open Society Initiative for West Africa (OSIWA) under the Missing Persons Register’s Population and Amplification Project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter