Looking Ahead: Will Shortages Of Food Follow Nigeria’s Floods?

With massive flooding that has washed away unharvested crops worth billions of naira, there are reasons to worry about looming food scarcity in the country.

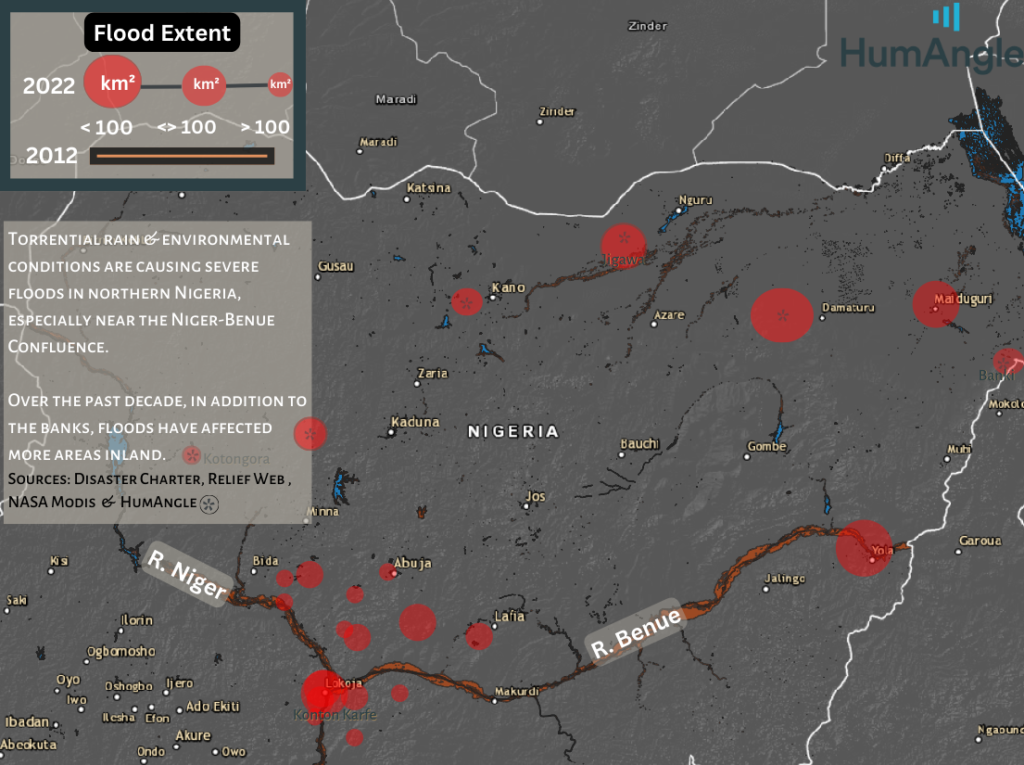

The ongoing flooding across Nigeria has left many rural communities waterlogged. Farmers fleeing the natural disaster in the North have given up their properties and farm investments, prioritising their survival. Combined with the already adverse effects of insecurity and climate change on agricultural outputs, observers say the crisis will push the country faster towards food insecurity.

Abubakar Muhammad, a 55-year-old farmer from the Mozum District of Bassa, Kogi, says his entire rice, maize, and cassava crops have withered. He has lost about 40 per cent of his annual income of ₦3.5 million ($7,940). For Alhassan Salisu Adakeke, another farmer from the nearby Diroko District, what he has lost is about a third of his annual income of ₦1 million ($2,270).

Exactly 10 years after the disastrous flooding of 2012, this year’s floods are unprecedented. Although the Nigerian Meteorological Agency (NiMet) warned against high rainfall and massive flooding, farmers in Kogi appeared to be relaxed, knowing that since 2012, the annual trend had been of erratic but manageable river outpours that were of benefit to them.

“Ordinarily, flood is welcome because it brings alluvial soil for rich harvest; it would also bring plenty of fish,” said Dr John Egwemi, the royal father of Ibaji Local Government Area.

This year’s flooding is particularly disastrous because of a massive increase in rainfall which forced the release of water from various dams in Nigeria and the Lagdo dam in the neighbouring Republic of Cameroon.

The flood neither started nor ended in Kogi. And so the extent of its damage on farmlands across the country portends food scarcity in the coming months.

Weighing the losses

Nigeria’s Minister of Humanitarian Affairs, Sadiya Umar Farouq, revealed that this year’s flooding has destroyed over 332,327 hectares of land across 31 states.

Most agricultural losses were, however, recorded in rural communities where about 70 per cent of the population relies directly on farming. The crops cultivated here are also the mainstay of the food supply chain nationwide.

From Adamawa and Yobe in the Northeast to Jigawa and Kano in the Northwest; Benue, Kogi, and Niger in the North-central; and Anambra, Bayelsa, and Delta in the South, there are many Nigerian states where floods have submerged farm investments worth billions of naira in less than three months.

Losses were more severe in the North-central region, where Rivers Niger and Benue, the two largest rivers in West Africa, meet at a confluence in Kogi.

Two examples – one of small farm holders and the other of a food and agri-business company – illustrate the weight of crop damages caused by floods in the region. In the Ibaji area of Kogi alone, which is almost fully submerged in floodwater, over 1,000 farmers have lost an estimated ₦2 billion ($4.5 million). In the neighbouring Nasarawa State, Olam’s $20 million agricultural investment covering 4,400 hectares of rice farm in the Rukubi Doma area was heavily affected.

The flood is already receding in the Northeast and Northwest. According to Dr Egwemi, however, it is a different story in the North-central, particularly Kogi. “A few days ago, we (started) noticing that the flood is no longer surging. But we cannot say it is receding. It is like a standstill position. We are hoping that after this standstill position, it will start to go back to the riverside.”

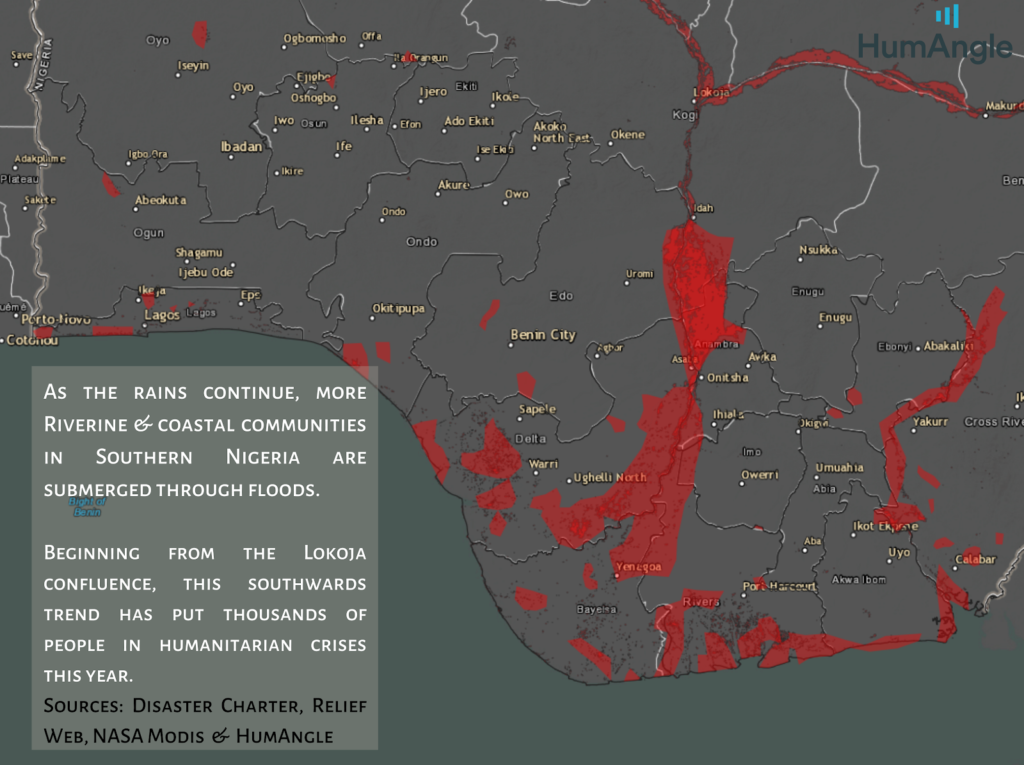

Now, as the water drains southwards into the ocean, more dreadful effects are likely to be seen in Southern Nigeria.

Although there are no official statistics to support this, an analysis of media reports shows that rice is the most destroyed of all the damaged food crops. Others are wheat, cassava, yam, and maize.

Beyond the destruction of crops on farmlands, the floods have other devastating effects on food security. A huge amount of grains reserved or hoarded in stores, at least in Kogi State, have been destroyed by floodwater. Local sources told HumAngle that the large-scale food stores close to the Kpata market in Lokoja and those around Okanga market in Diroko, Bassa, have all been submerged.

This is in addition to multiple fish ponds that have been washed away. Yet, the flood has destroyed many roads, disrupting the food supply chain. Daily Trust, a local newspaper, reported on Sunday that fewer trucks were making it to Southwest Nigeria from the North. Consequently, food prices have begun to creep up.

The disaster has also led to serious losses in terms of fatality, injuries, and property destruction.

Looming hunger, inflation

Although Nigeria has for many years been a major importer of food items, Nigerians primarily depend on locally produced food.

Data from the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) shows that 57 per cent (nearly 6 million tons) of the rice consumed in Nigeria is produced within the country, while the rest is either imported or smuggled in. Unfortunately, a significant percentage of this has been destroyed by floods affecting the Olam rice farms alone.

Shortfalls in local food production make food price inflation and hunger imminent. The Kpata market in Lokoja is, for instance, a regional market where people from all over Nigeria come to buy rice and other perennial crops from local farmers. According to locals, on market days, not less than 100 engine boats capable of carrying 300 to 400 bags of rice, maize, and other crops convey foodstuff to the market from Mozum District alone.

With the entire district, except the Sabongari community, under floodwater, farmers have nothing to take to the markets this year. “Even at the moment, whoever manages to take small cassava or other crops to the market, you wouldn’t want to hear the kind of price they are charging; even as we are speaking, things are not easy,” Muhammad lamented.

In the Northwest, grain merchants from Funtua market told HumAngle that the food supply is continuously decreasing. Speaking on the phone from the key regional market hub, they said crops from areas that are unaffected by flooding are in the middle of the process of being harvested. The grains are still being processed and have yet to be taken to market.

With flooding causing a serious decline in local food production, grain sellers are predicting farmers may hold back their produce in fear of a looming food shortage. Hoarding, an annual practice in the country, may increase grain sellers said. Speculators buying more in anticipation of shortages could drive food prices even higher.

All these are indicators that the already existing trend of food price inflation would likely get worse. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, food inflation in Nigeria rose by 20.8 per cent in September, which is the highest rate since 2005, creeping up from 20.5 per cent in the previous month.

Even before the flooding, food insecurity has been a source of worry in Nigeria. The twin monsters of insurgency and armed violence have been obstructing farming and access to local markets in the Northeast and Northwest. As a result, about 8.4 million people – including displaced persons – are food insecure in the Northeast, just as 70 per cent of the population is below the poverty line in the Northwest.

Northern Nigeria supplies most of the country’s food items. With insecurity ravaging the entire region, it is unsurprising that since March, FAO had estimated that about 19.4 million Nigerians would face food insecurity across the country between June and Aug. 2022.

Now that flooding is added to the already bad situation, FAO hints that cereal production would likely decline by 3.4 per cent. UN spokesperson Stephane Dujarric said last week that the world body was “gravely concerned that the flooding will worsen the already alarming food insecurity and malnutrition in Nigeria.”

Responses

The National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) is already distributing 12,000 metric tons of food commodities to persons affected by floods across the country. Some of the victims, however, lament that government efforts aren’t enough.

“They come with indomie, bags of rice, and maize for people to cook and eat. And it can’t sustain even a family for one week. Not even two days,” Adakeke groaned.

Locals, including traditional rulers, have shown their preference for the government to invest more in long-term measures, rather than intervening in food markets, such as the dredging of rivers and the construction of dams at strategic locations to prevent recurrences.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter