Life Under Bridge: The Hard Realities Of Displaced Nigerians In Lagos

The world of bridge dwellers comes in many facets as many displaced people struggle in Nigeria’s economic capital in search of greener pastures.

Adedokun Olatundun, 65, lost her husband and three of six children to the age-long communal crisis between Offa and Erin-Ile communities in the Oyun area of Kwara, North-central Nigeria, in 2006. As she ran in a hurry, a fourth child went missing.

The land boundary crisis between Offa and Erin-Ile has lingered for many years and the recurring waves of clashes have resulted in many casualties. The conflict has also weakened the social fibre holding the two communities together in spite of their cordial history.

Olatundun’s is one of many families affected by the crisis. Aside from losing some of her relatives, she was displaced alongside two children. Today, they remain homeless as they struggle to survive in Lagos, Nigeria’s commercial hub.

Olatundun told HumAngle she has been living under the popular Oshodi bridge for the past 12 years. She wakes up on a daily basis to hawk bags of sachet water. When she is tired, she sits beside the bridge so she can sell water for those who branch to eat.

Most times, she feeds herself with the leftovers from others. When the night falls, she pays a “security fee” of ₦100 to agberos, also known as area boys. The word ‘agbero’ loosely means “to usher passengers”, but it has now become a synonym for thuggery. The agberos are typically at bus stops, motor parks, and sometimes in front of shops and construction sites, demanding money illegally.

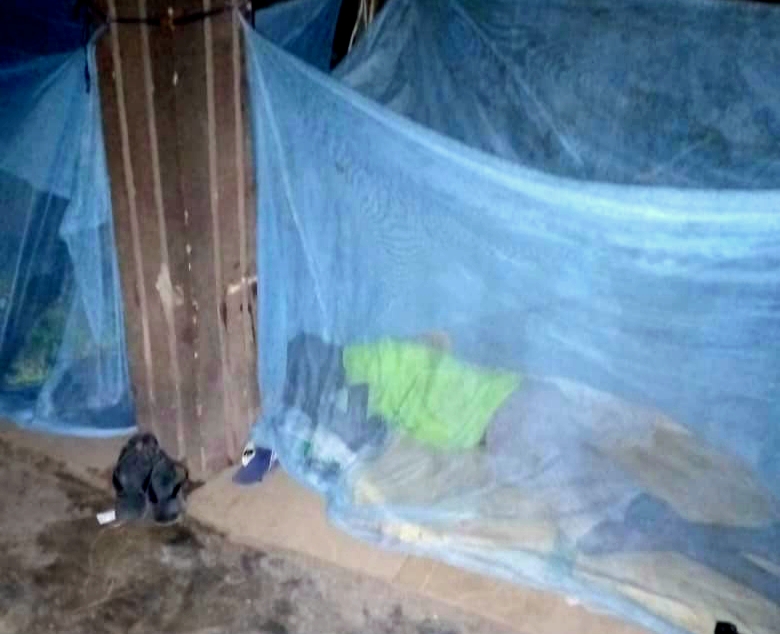

“I sleep under the bridge and sometimes in front of shops after the owners have closed. It is compulsory for us to pay, else they will use a razor blade to cut our pockets or bags and then run away with the little stipends we make from our daily sales. Living under the bridge at my age is sad, but I have nowhere to go,” said Olatundun.

“The two children I survived the crisis with are also trying to make things work, but it has not been easy.”

One of them travelled to the Benin Republic to work as a housekeeper, but she has not heard from her since 2018. The last child, who works as a bus conductor, makes sleeping under the bridge easier for her.

“I have nowhere to go because I have no one to take care of me. I don’t believe that this suffering will stop. I am simply waiting for the day I will sleep and not wake up again, then I can ask God why he made my life so miserable.”

Displaced by insecurity

Like in many states, the idea behind the construction of overhead bridges in Lagos was to reduce traffic congestion. But the flyovers now serve as homes for internally displaced persons and the homeless.

HumAngle gathered that most of the people who reside in these places have no specific sources of income. They disperse when the day breaks to find jobs. While the men are often into cart pushing and work with commercial buses as conductors, the girls and women serve as attendants to roadside food vendors.

They usually gather around roads leading to markets in busy areas like Oshodi, Ketu, Obalende, Mile 12, Ojota, and Idumota.

Saidu Garba, 36, is one of the cart pushers in Obalende. Aside from helping people carry loads from park to park, he also moves from one refuse dump to another, scavenging for scrap metals to sell to dealers so he can feed himself and pay necessary bills.

He fled Maiduguri, capital of the northeastern Borno State, following a 2012 Boko-Haram attack that led to the death of his parents. His wife and son moved to Zamfara, which has since become the epicentre of terrorism in the Northwest.

Although Obalende underbridge does not offer the security of a regular house, Garba feels more comfortable here as he sets out daily and returns at night to lay his head. He has resigned to fate and hopes to invite his wife soon. Asked how he would cope under the bridge with his family, he replied that he would rather struggle with them in Lagos than “allow evil befall them in the north”.

Garba told HumAngle he would continue to work hard to ensure that his son finds his way into the Nigeria Army to avenge the death of his parents. “I would not have abandoned my factory work in Maiduguri if not for terrorism. I want my child to help fight insecurity.”

One day he would never forget since he moved to Lagos is Jan. 28, 2015. A mob had beaten him up; he had mistakenly caused a commuter’s luggage to fall into the gutter. “Before I could say sorry, people gathered and started beating me till my face got swollen. It was an unforgettable day of many days of trouble in Lagos,” he recalled.

Musa Adamu, 25, was also displaced as a result of insecurity in Borno and has been in Lagos for 1o years.

“I am a cart pusher and sleep anywhere. When it rains, I will put my mat in my armpit till the rain stops so I can lay it back,” he said. “The government and people of the state have repeatedly accused us of being responsible for thuggery, so the police usually arrest us. We have no identity card to separate us from the bad guys.”

The price for homelessness

Adewale Sodiq, 31, has lived under the Oshodi flyover for nearly two decades following the death of his parents. He found himself on the streets of Lagos by fate but has lost hope of a good life.

From Ibadan, in the Southwest, Sodiq, without any particular destination in mind, stopped over in Oshodi. Now an adult, he remains homeless under the bridge, facing the future with uncertainties.

“I was 14 years old when I got to Lagos. I was involved in sweeping the streets and washing toilets. The thugs who claimed to be our brothers were collecting the contract on our behalf. They would make us do the work while they took the money. They gave us whatever they wanted with the impression that we were apprentices learning the art of thuggery,” he recalled.

Besides serving as a shelter for the homeless, most underbridges are hideouts for hoodlums who smoke hard drugs, drink liquor, and engage in other illegal activities. Police officers in search of those involved in crime usually arrest innocent people like Sodiq, who has repeatedly been a victim.

In 2011, the police raided homeless Nigerians at midnight in a bid to arrest hard drug dealers, but many of those arrested were innocent. Sodiq was one of them. He was charged to court alongside others and was later convicted. He then spent three years at the Kirikiri Maximum Security Prison in the Amuwo Odofin area of the state.

Since he had no other shelter, he returned to the bridge after serving his jail term. He was again arrested three months after his release. This time, he spent six months at Potoki Prison in Badagry. “I have been arrested more than five times and I have toured Kirikiri and Potoki prisons twice. Despite all I have faced in life, I’m still here because I have no place to go.”

Sodiq’s story is similar to that of his friend, Quadri Rasheed, 31, a bus conductor who claimed to have been living on the streets of Lagos since he was 17 years old. He confirmed how ‘senior prefects’, his slang for thugs, usually extorted him until he grew old enough to challenge the exploitation.

Due to his popularity as a young hip-hop star in Oshodi, he says he is flocked by a lot of ladies who live under the bridge too. Even as he struggles to find his daily bread, he has impregnated two of them. Asked how he plans to take care of the ladies and the unborn children, he said, “I know I have made a serious mistake, but I pray that God will show me the way and won’t make the children end up like me.”

Respect for senior citizens

Muhammed Amina, 55, was one of the victims displaced by the flood in Goronyo, Sokoto State, in 2010. Although she was among those who moved to the housing unit camp built through donations from the Federal Government and civil societies for victims, she left after her husband was involved in an accident that claimed his life in 2017.

“I had to leave for Lagos after his burial because I want a better future for my children. There was no food and work for me in Sokoto, and on getting to Lagos, there was nowhere to stay except under the bridge in Costain.”

She told HumAngle she needs assistance from well-meaning Nigerians because her earnings from street sweeping are not enough to feed and clothe her children let alone rent an apartment or educate them.

Asked how difficult it is to pass the nights on the streets with six children, she responded, “The streets respect the old regardless of your tribe.”

“Most of the people living under bridges in Lagos are victims of different circumstances, so they respect some of us with bigger problems. There is no tribe when it comes to surviving on the streets. There is harmony in our diversity. Some of the thugs who claim to be the landlords under the bridge usually collect ₦100 from us to pass the night, but they respect older squatters.”

Muhammed Olayinka, 50, also confirmed that older homeless people are more respected. He left his home in his early 20s after his parents died to pursue a career in Fuji, a genre of music popular among the Yoruba people of Southwest Nigeria.

“I am still pursuing my career, hoping that I will meet a helper one day. There are several days I feel like killing myself, but I get encouraged by younger ones that I should continue my work. I sing for travellers at motor parks and feed myself with what I make from my performance. We still thank God that we are alive anyways.”

Public complaints amid traffic robbery

Meanwhile, there have been a series of complaints by Lagosians over an upsurge in traffic robbery. The robberies, which take place both day and night, are said to be perpetrated by thugs living under flyovers.

The common areas where these crimes occur are CMS, Costain Bridge, Maryland, Ikorodu road, Gbagada, Mushin, Orile, Oshodi bridge, and other heavy traffic routes.

According to those who have witnessed the activities of the robbers, they accost them with weapons by tapping the side windows of their cars. They then rob them of properties they can easily carry. They sometimes damage the car or attack the victim if they fail to wind down.

Speaking of her robbery experience, Racheal, a civil servant, said she begged for transport fare after her bag was snatched in Oshodi. “I encountered the robbers in late May around 7 p.m. on the bus. I had my bag on my lap, and all of a sudden, somebody ran through the window and snatched my bag.”

While thugs carry out various forms of crimes around flyovers/under bridges in Lagos, multiple sources told HumAngle that the police often arrest innocent homeless people in their place.

In May, the Federal Ministry of Works and Housing issued a month ultimatum to those living under bridges in Lagos, adding that it would commence enforcement from June 9. He did not speak on the efforts by the government to provide alternative shelters for them.

Hakeem Bello, Special Adviser on Communications to the minister, Babatunde Fashola, did not respond to calls and text messages. Our reporter encountered the same challenge with Gbenga Omotosho, Lagos State Commissioner of Information.

Two months after the announcement, the situation remains the same. “We have nowhere to go,” a resident said during a visit to Apongbon Underbridge.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter